Enough cyberpunk—it's solarpunk's time to shine

Rather than imagining another dystopia, solarpunk envisions futures where tech and the environment can co-exist.

I’ve loved cyberpunk since I was old enough to dig through a second-hand bookstore on my own. But I’m tired, and I know I’m not alone. It’s hard to keep waving a flag for a genre that's so often boiled down to a Hot Topic look and recycled stories. Perhaps the final nail in the coffin was the shambling disappointment of Cyberpunk 2077, which CDPR is still determined to keep working on. What many people recognize as cyberpunk today is mostly cosmetic, and reusing that aesthetic again and again is becoming tedious and meaningless.

"What bothers me about cyberpunk is that it often gets carried away fetishizing the high-tech world it is ostensibly critiquing," says indie designer Phoebe Shalloway. "It makes tech look sleek, sexy, and cool." Shalloway has a different interest: she makes explicitly solarpunk games, which offer a fresh new way to imagine the future. Solarpunk still includes working with technology, but with a positive focus on sustainability, community, and radical change to the world as it is today.

Solarpunk isn’t just about recycling and wind power—it also involves progressive new attitudes toward technology that don’t involve CEOs calling the shots

Cyberpunk is often married to dystopia because of how it began—in the west it spawned from the Cold War, Reaganomics, and the perceived threat of an Orientalized, globalized future. But the reality is that modern life unironically buys into cyberpunk tropes of tech-fueled consumerism and corporate supremacy.

Ultimately, the way we portray fictional futures has a real impact on pop culture and our imaginations. "When all we see are bleak gritty cyberpunk realities, it becomes a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, where this is the only way we know to imagine the future," Shalloway explains. And as climate change and sustainability become critically urgent issues, more people have become vocal about the need for something different. And that alternative is solarpunk: a vibrant young genre that focuses on sustainability, innovation, open-source technology, and collective action.

The term was coined in 2008 on the blog Republic of the Bees, and is, in many ways, a post-cyberpunk idea that emphasizes positive long-term solutions. It’s not the grimdark machine-dominated future that we’re so used to seeing.

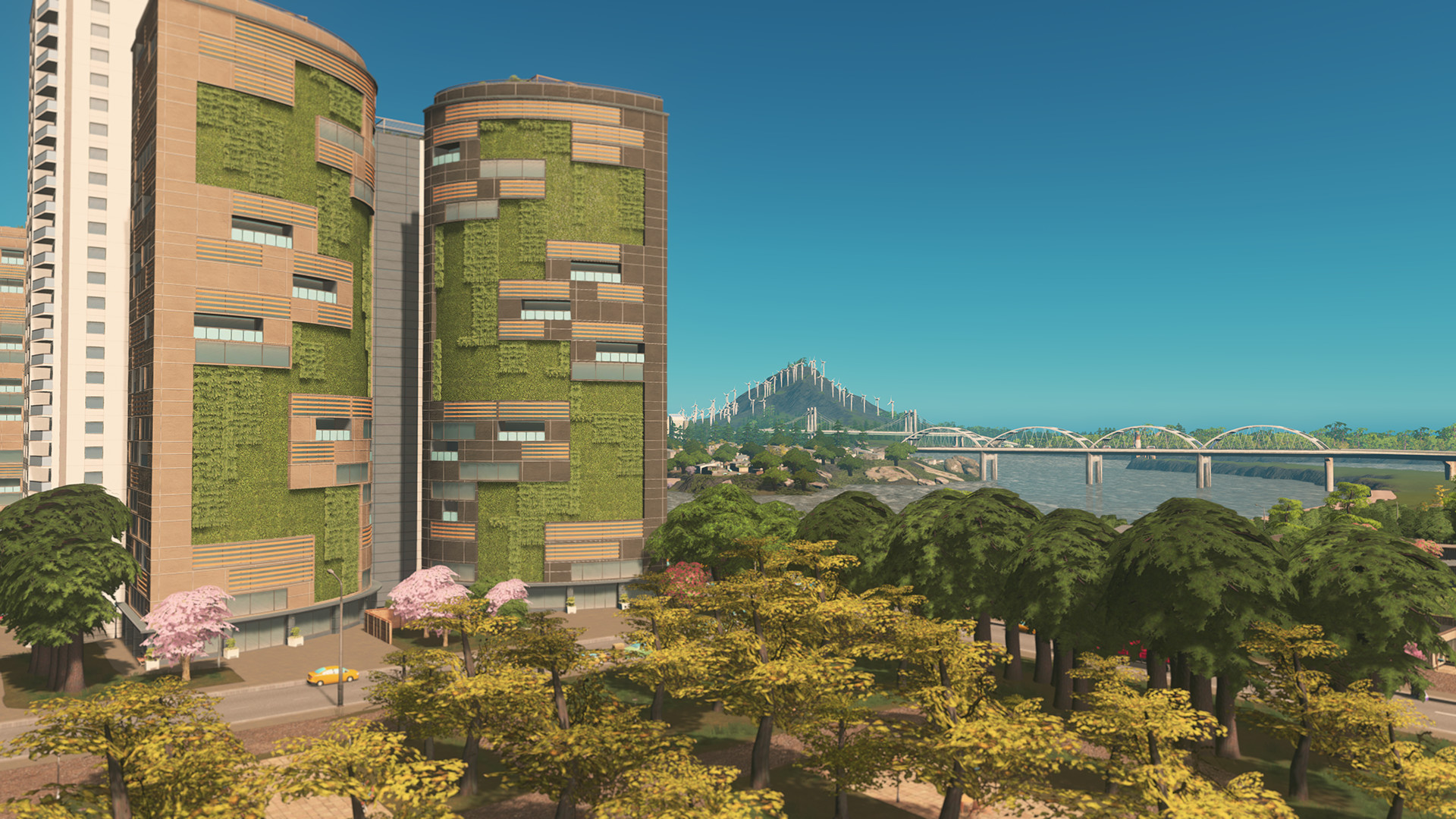

We can already see glimpses—at least aesthetically—of solarpunk ideas in some popular games. Visually it’s similar to the utopian sun-drenched world of Aurora in Ghost Recon: Breakpoint, where tech pioneer Jace Skell introduces a peaceful island filled with creativity, innovation, and sustainable lifestyles (of course, this seemingly perfect place turns out to be pretty problematic). On a more straightforward level, Cities Skylines has a Green Cities expansion that lets players create eco-friendly infrastructure and buildings.

But solarpunk isn’t just about recycling and wind power—it also involves progressive new attitudes toward technology that don’t involve CEOs calling the shots. In games, it’s no surprise that small indie developers are doing the most meaningful work in this area. It’s impossible to achieve a new world without also including radical politics—the kind of stuff you’re mostly going to see in subculture communities that challenge the status quo, from urban farms and makerspaces to mutual aid groups that focus on hyperlocal problems like food distribution, social outreach, and medical help.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

In the popular PS4 game creator Dreams, Solarpunks.net recently shared a soothing Japanese-themed vision of a solarpunk future by user TRIX9. "Imagine for a moment, a world in balance," the description reads. "A vision of the future that seeks to offer a viable alternative to a much fantasized dystopia. An idealistic aesthetic where tech and agriculture coexist." The short clip offers up a luminous, futuristic cityscape with wide sidewalks, abundant greenery, and hints of clean energy in the form of a hot air balloon—a throwback to old-school sci-fi where dirigibles ruled the skies.

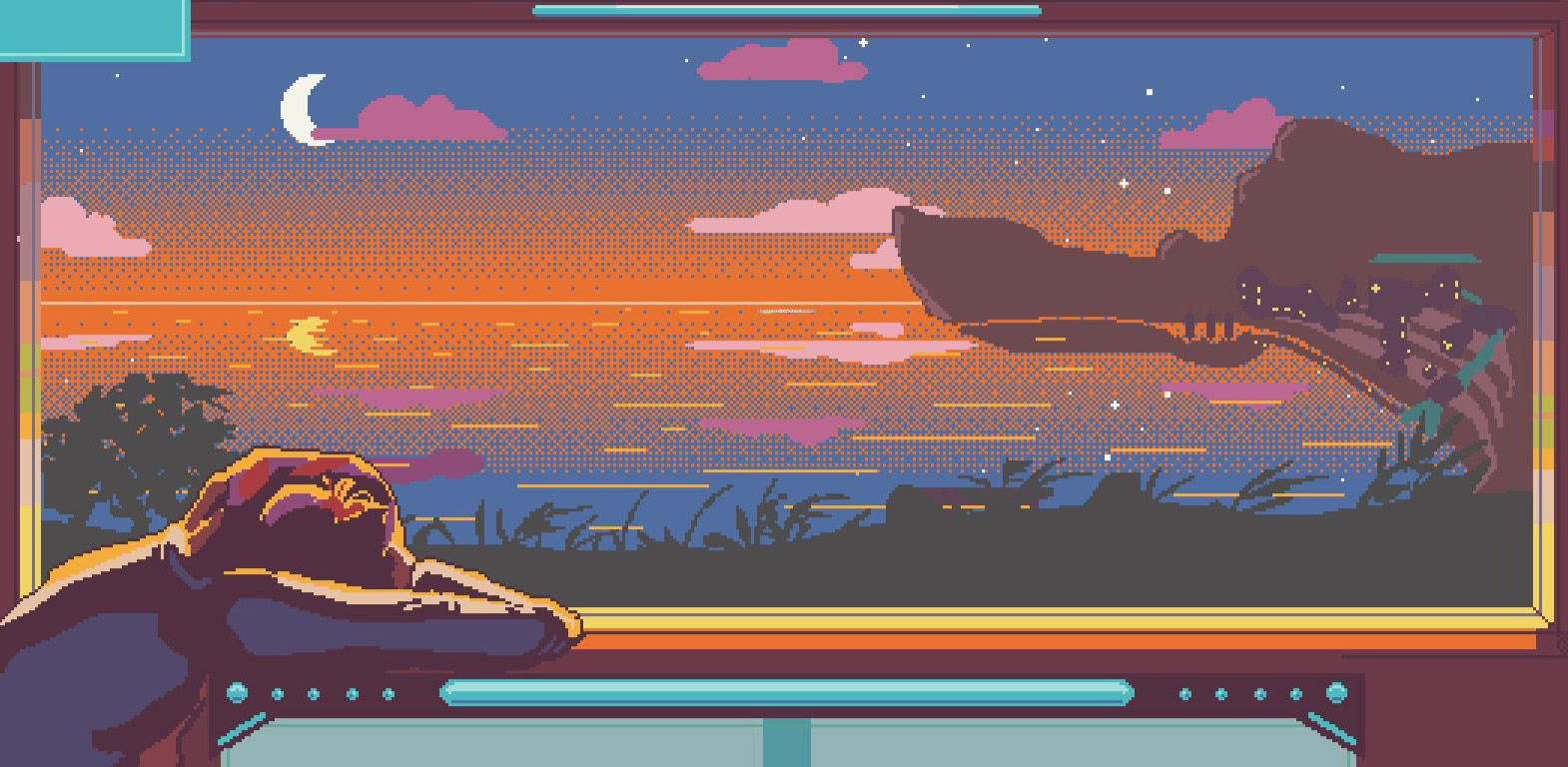

Exploring the solarpunk tag on itch.io unearths small interactive fiction projects like Mycelium Child, Epoch of Rest, The Forest Train, and a pixelated student demo, Solare. Mycelium Child, produced for the Extra Credits 2020 "Take Care" Game Jam, is set on a mushroom-laden alien planet that introduces you to slice-of-life experiences in the community. The Forest Train paints a broader atmospheric picture with forest communes called qithyds, well-functioning public transport, and open-source technology and information.

"The extreme negativity of cyberpunk, together with its rule-breaking possibilities is very appealing and can be experienced without facing any consequences in the real world… who doesn’t want to be a cool cyborg?" writes Lost and Found, the student team behind Solare, in an email. "Solarpunk is a social counter-design to cyberpunk, because it is one of the few optimistic and realistic visions of the future. [We] want to be able to look towards the future with a clear conscience," they continue. "It is the hope to build a society together that is not destructive and not afraid of different cultural influences."

Phoebe Shalloway’s Solarpunkification is a quick 10-minute game where you play a guerrilla gardener trying to transform their city while avoiding the cops. But it’s her college thesis project Even in Arcadia that dissects the politics and economics that shape the need for solarpunk—the need for radical change. The game follows a small group of friends at a launch party for Arcadia Gardens on a new planet, described as a "nostalgia theme park" designed to recreate ancient Earth nature. One character, Jack, wishes to leave her privileged place in Arcadia to live on an obsolete planet used as a garbage dump—much to the horror of her husband, Lio, and apathetic tech titan Ozymandias. Arcadia, while pristine and perfect, isn’t actually real, and comes at a cost.

In one short "cycle" of the party, Shalloway paints an intense picture of the effects of late-stage capitalism, startup tech culture, and its impact on community and empathy. She was inspired by immersive games like Gone Home and Tacoma, and motivated by real-world phenomena like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and the advent of plastic-eating bacteria.

It’s a lot easier to look at our current society and point out what’s bad about it than to imagine what a really good sustainable society would look like

Phoebe Shalloway

"A role of artists in our time can be to prepare society for a positive response to the coming changes," she writes in her 2018 senior thesis. "We can make strange our world and behaviors so that we might break out of society’s rules and develop new ones. If the bacteria can do it, we can do it, too."

It’s this optimistic drive that illuminates solarpunk as a genre for the future, based on problems that we struggle with in the present. Unlike cyberpunk, it’s stubbornly idealistic in its pursuit of a more livable world. Collective action and sharing are vital to its message: "to live comfortably without fossil fuels, to equitably manage scarcity and share abundance, to be kinder to each other and to the planet we share."

So why aren’t we seeing more solarpunk games? For one thing, it’s still a growing subgenre that can be difficult to work in. "From the writer’s side it can be intimidating and difficult to try to depict a solarpunk world," Shalloway says. "It’s a lot easier to look at our current society and point out what’s bad about it than to imagine what a really good sustainable society would look like. But there’s a real need for that image."

It’s also an inherently anti-capitalist movement, which doesn’t fit neatly into the business of game development or how we spend most of our time in games acquiring things—grinding or farming loot and resources is a huge driving factor for many MMOs and RPGs. The challenges of growing a collective farm or dismantling oppressive institutions aren’t as viscerally thrilling as an anything-goes battle royale or fighting waves of demons. Most triple-A games are focused on individual player rewards, so it would be challenging to integrate solarpunk principles like community action and mutual aid into a mainstream game.

For devs and players, cyberpunk lends itself especially well to game environments: the moody mega-city, neon lights drenched in rain, and hi-tech mechanics are easily recognizable symbols for a dystopian future where it’s easy to slip into the role of anti-authoritarian outcast. More importantly, cyberpunk is founded on capitalism and conflict—its visual language serves to illustrate how megacorporations (or, in stories like Snow Crash, feudal corporate kingdoms) rule the world. "It’s really easy to get cynical when you start thinking about capitalism," Shalloway notes, "which is actually exactly why cyberpunk is so much easier of a genre to write for than solarpunk."

Despite its optimism, solarpunk isn’t necessarily all sunshine and roses. "Solarpunk can bring the conflicts and even aesthetics of cyberpunk into its worldbuilding too, can have characters and settings that reflect those high-tech capitalist values," says Shalloway. "The difference would be that solarpunk would not fetishize those characters and settings; it would use them as a foil, an antagonist, or something to work away from. It needs to emphasize building something new and different outside of the cyberpunk world."

On the bright side, there are already more hints of socially and environmentally responsible messages creeping into more games. Narrative-driven indie game Venice 2089 is set in the titular city where water is reaching critical levels (in present-day reality, the city is experiencing extreme tide activity due to climate change). Crafting/survival game Common’Hood, currently in development, digs into socioeconomics as the player rebuilds a "post-crash community"—still using automation and robots—in a way that harmonizes with the environment.

But perhaps because mainstream games are far more commodified and complex products than books, solarpunk may never get a chance to reach a wider gaming audience. Sci-fi legends like Kim Stanley Robinson are turning to climate fiction to make sense of our increasingly endangered planet—an approach that the novelist describes as "angry optimism."

Perhaps the problem isn’t that solarpunk isn’t suited to mainstream perception of video games—the problem, then, is that we simply haven't fully realized how angry we should be about our current planetary predicament.

Alexis Ong is a freelance culture journalist based in Singapore, mostly focused on games, science fiction, weird tech, and internet culture. For PC Gamer Alexis has flexed her skills in internet archeology by profiling the original streamer and taking us back to 1997's groundbreaking all-women Quake tournament. When she can get away with it she spends her days writing about FMV games and point-and-click adventures, somehow ranking every single Sierra adventure and living to tell the tale.

In past lives Alexis has been a music journalist, a West Hollywood gym owner, and a professional TV watcher. You can find her work on other sites including The Verge, The Washington Post, Eurogamer and Tor.