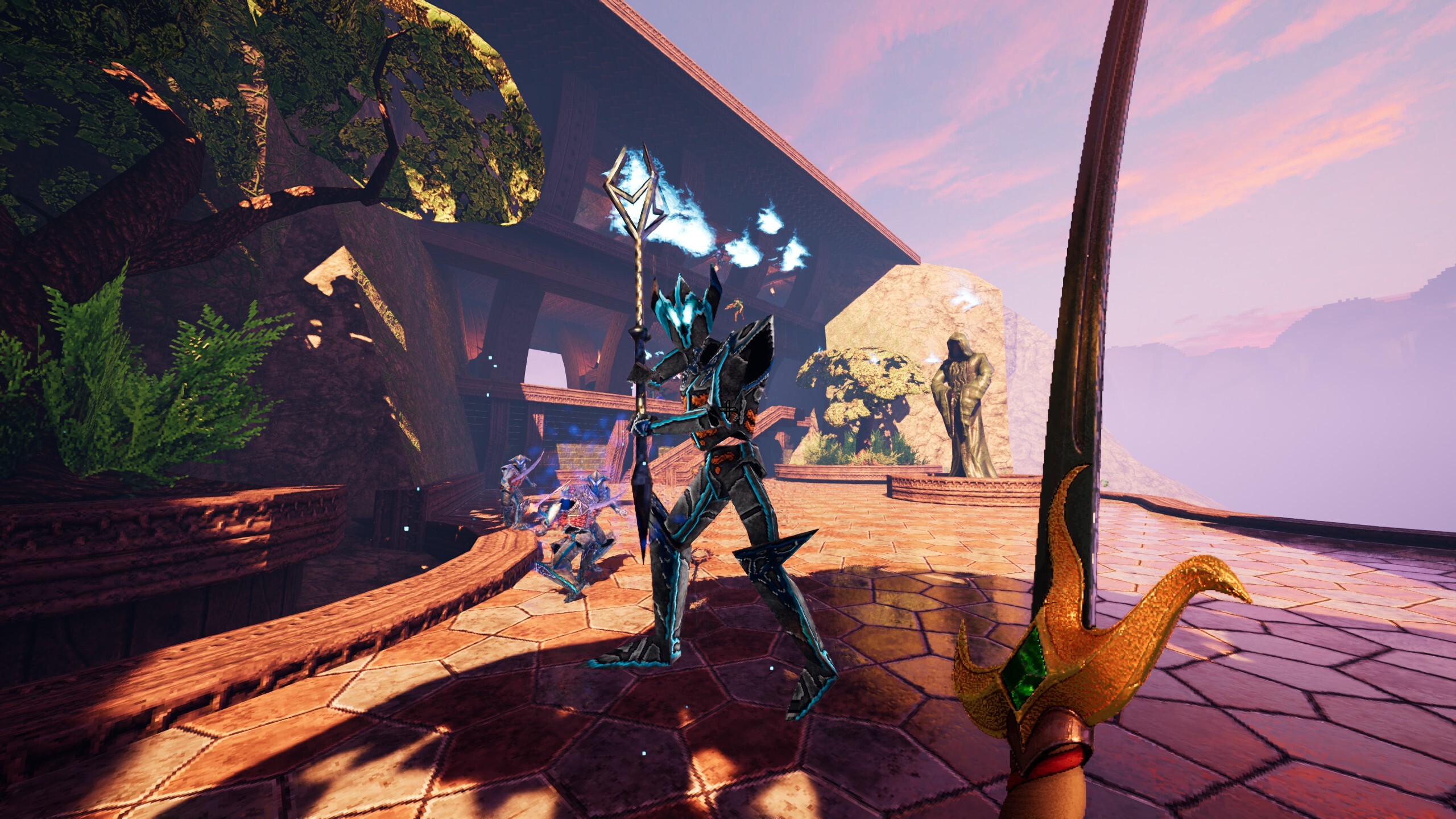

Launched in 2019, Amid Evil is one of the best shooters to emerge from the retro-FPS revival. Combining colourful and creative levels with some incredible, Hexen-inspired magical melee weapons (including the phenomenal Star of Torment, one of my favourite FPS weapons in ages), it sits proudly alongside New Blood Interactive's other "boomer shooters" like the incomparable Dusk and the Early Access phenomenon Ultrakill.

Yet Amid Evil didn't cease development in 2019. Creator Indefatigable has released several updates to the game since its launch, the most significant of which is the recent RTX update, which adds ray tracing and Nvidia's DLSS 2.0 tech to the game. And it makes for a fascinating showcase of a technology that sometimes struggles to show off what it can actually do.

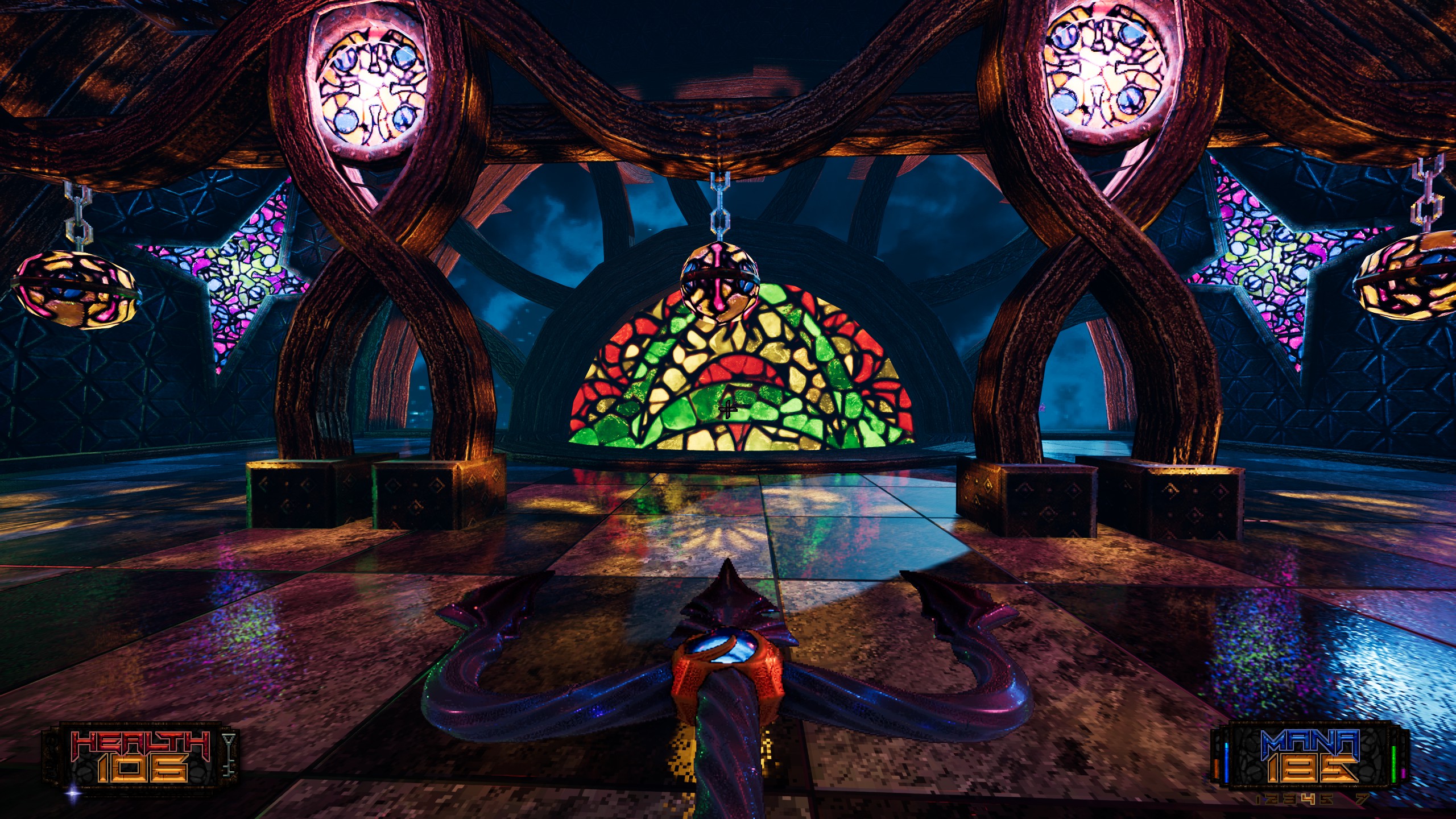

Ray tracing, for those unaware, essentially simulates how light reflects and refracts off surfaces in real-time, resulting in visual effects like accurately simulated dynamic shadows, more realistic-looking materials, and complex reflections off smooth surfaces like glass and water. The crucial element here is "real-time", meaning it also simulates how lighting and shadow in a virtual environment changes based on how lights-sources and objects move. For example, it can simulate how light filtering through a stained-glass window affects the light patterns of the floor as the sun tracks across the sky.

It's incredibly powerful tech. Revolutionary, in fact. But thus far its impact upon the games industry has been oddly muted. It hasn't radically altered how games look in the way that, say, hardware acceleration did in the mid '90s. In fact, with many games that support ray tracing, you'd be forgiven for not noticing the technology at all.

There are a couple of reasons for this. The technical demands of ray tracing have until recently limited its viability, although this is now less of a problem thanks to DLSS and native support for the tech in the latest generation of consoles. The bigger problem ray tracing faces, though, is how it has been framed as the next step toward photorealistic graphics.

The issue here is that games have become exceedingly good at faking what real-time ray tracing does for real. Developers have spent years, even decades, figuring out how to replicate the ways in which light affects an environment. There are a whole range of solutions dedicated toward specific aspects of lighting. Dynamic lights, dynamic shadow, soft shadows, volumetric lights, specular lights, ambient occlusion, and so on.

When put together by an experienced team of environment artists, discerning the difference between a "realistic" ray-traced scene and a realistic non-ray-traced scene is difficult. You can probably spot the differences in a side-by-side screenshot comparison, but when you're racing through a combat sequence in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare at 60FPS, your brain will struggle take in anything but the broadest strokes of the environment, let alone whether that puddle over there has ray-traced reflections or not. This isn't to say ray-tracing doesn't have a place in realistic graphics rendering, merely that you're unlikely to properly notice it, because the whole point of making something look realistic is to approach it with subtlety and accuracy.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

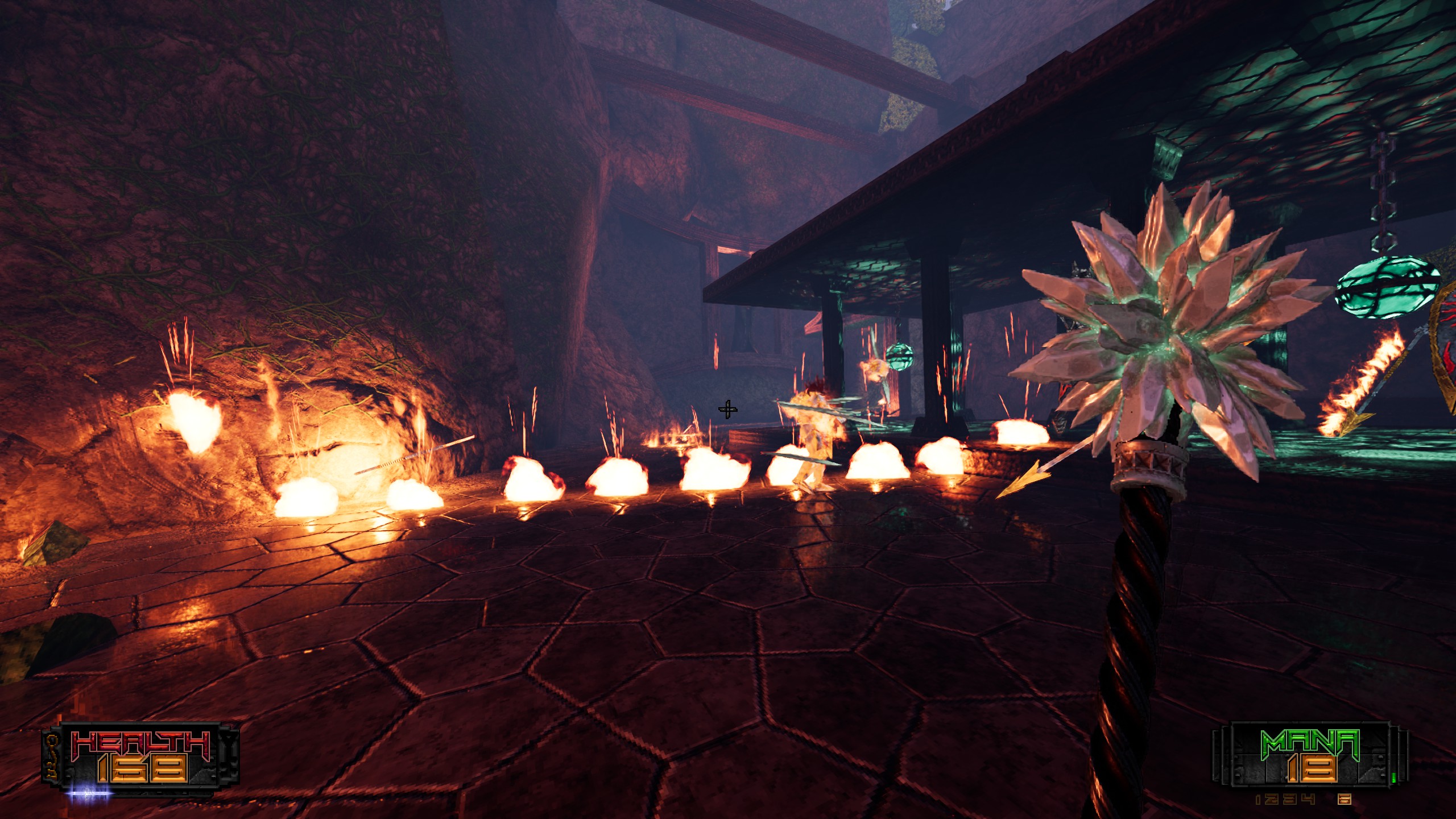

But this is not the only way ray tracing can be used, which is where Amid Evil comes in. Stylistically, Amid Evil is a highly unusual game, one that blends both old and new graphical effects. Its levels are designed to resemble the BSP-tree geometry of games like Quake and Unreal, while enemies are built out of chunky polygon blocks that resemble creatures out of Pythagoras' nightmares. One of its most impressive visual tricks are the weapons you wield, which are actually sprites. That's right, good old-fashioned sprites, only with normal maps and a host of other effects applied to make them appear as 3D objects.

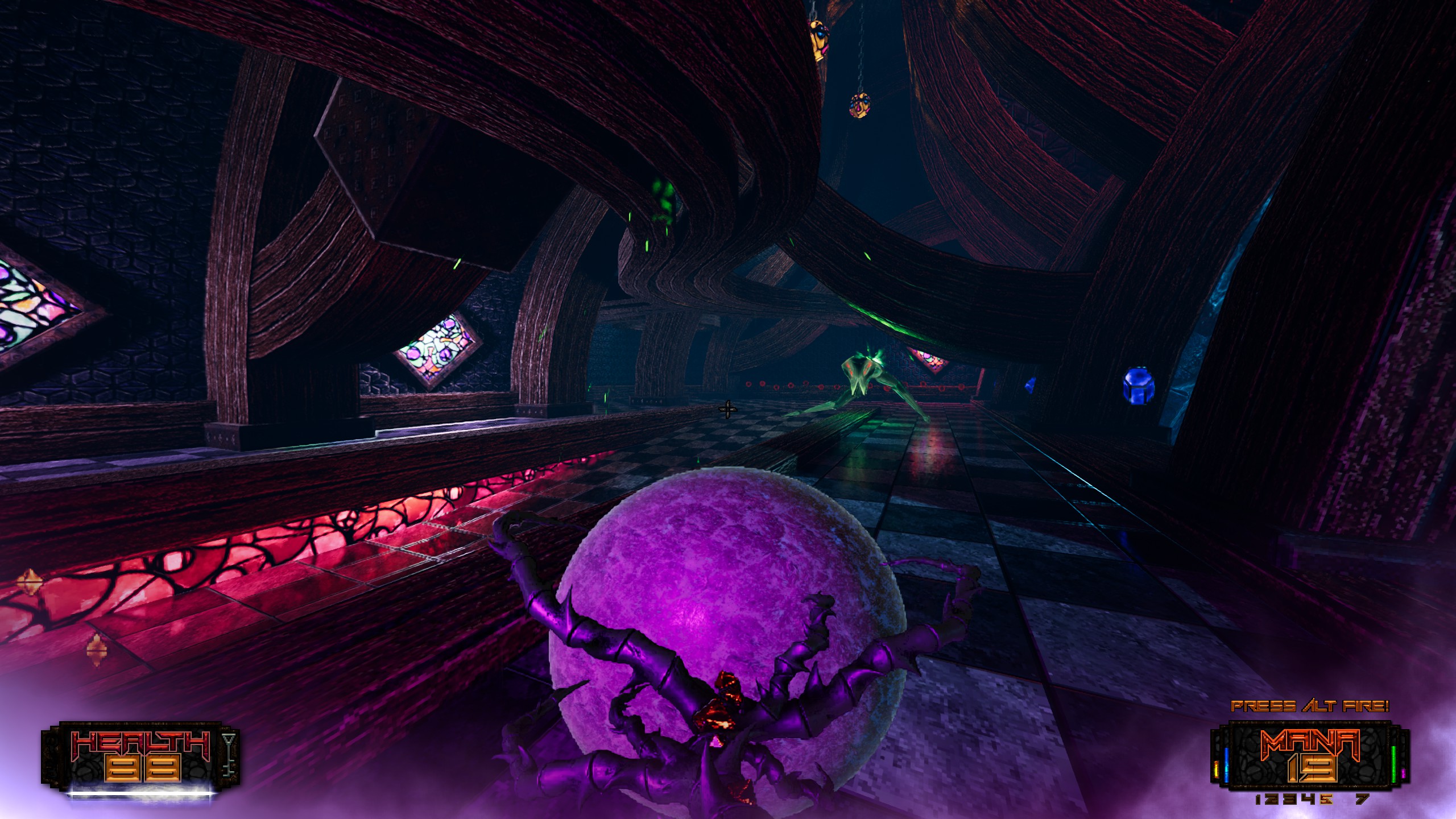

Combined with some excellent level design, twisting, looping spaces designed specifically to feel otherworldly, the result is a wonderfully surreal FPS. The way Amid Evil adds ray tracing compounds this effect. Suddenly you have id-tech 2.5-era coloured lights splashing across gun metal floors and rain-slicked stonework, and skeletal triangle-people casting Nightmare Before Christmas-style ray-traced shadows. The game's final chapter, named the Void, takes place in an abstract realm made almost entirely of reflective surfaces that zip and snap into place as you move around. It looked incredible the first time around; with ray-tracing it's positively spellbinding.

Amid Evil's use of ray tracing hints at another possible life for the technology, one that goes beyond making puddles and shadows look slightly more authentic. Realism is cool and all, but I want to see what ray tracing can do to unreal spaces, with combinations of light and reflectiveness and colour that aren't possible in the real world. Give the technology a platform where it isn't shackled by the constraints of realism, some hall-of-mirrors style prism world or a realm of inky shadows. Show me worlds comprised entirely of ray-traced sprites, or a PS1 era survival horror game with ray-traced dynamic shadows. I don't know if what I'm asking for is possible, or what the hell it would look like. I just know that I want gaming tech to do more than add reflectiveness to gun barrels in Call of Duty.

I'd also love it if Amid Evil was the game that spearheaded this push. The RTX upgrade is a great start, but it's retroactively applied to an existing design. Indefatigable is, however, currently working on a prequel expansion to the game called The Black Labyrinth. It may not be the studio's plan, but I'd love to see what it can do building its graphical hybrid shooter if ray tracing is a consideration from the start. I bet it'd look like nothing else on this Earth.

Rick has been fascinated by PC gaming since he was seven years old, when he used to sneak into his dad's home office for covert sessions of Doom. He grew up on a diet of similarly unsuitable games, with favourites including Quake, Thief, Half-Life and Deus Ex. Between 2013 and 2022, Rick was games editor of Custom PC magazine and associated website bit-tech.net. But he's always kept one foot in freelance games journalism, writing for publications like Edge, Eurogamer, the Guardian and, naturally, PC Gamer. While he'll play anything that can be controlled with a keyboard and mouse, he has a particular passion for first-person shooters and immersive sims.