Alone in Rapture: why vulnerability was Bioshock's greatest strength

The ingredients of vulnerability

A a designer, you should want your players to go: “I don’t know if I can make this,”

Followed by: “But I’m going to try,”

Which leads to “Wow, I made it! I feel great!”

Half-Life, for instance, shows you the tentacle monster and how scary it is, encourages you to get past it, and climaxes with this awesome moment where you torch it with a rocket engine.

Being alone is a great way to craft vulnerability. Think about how much scarier Predator is when there’s no one to watch Arnold’s back. He’s out there, on his own, fighting this alien thing. The ultimate action hero, utterly outgunned.

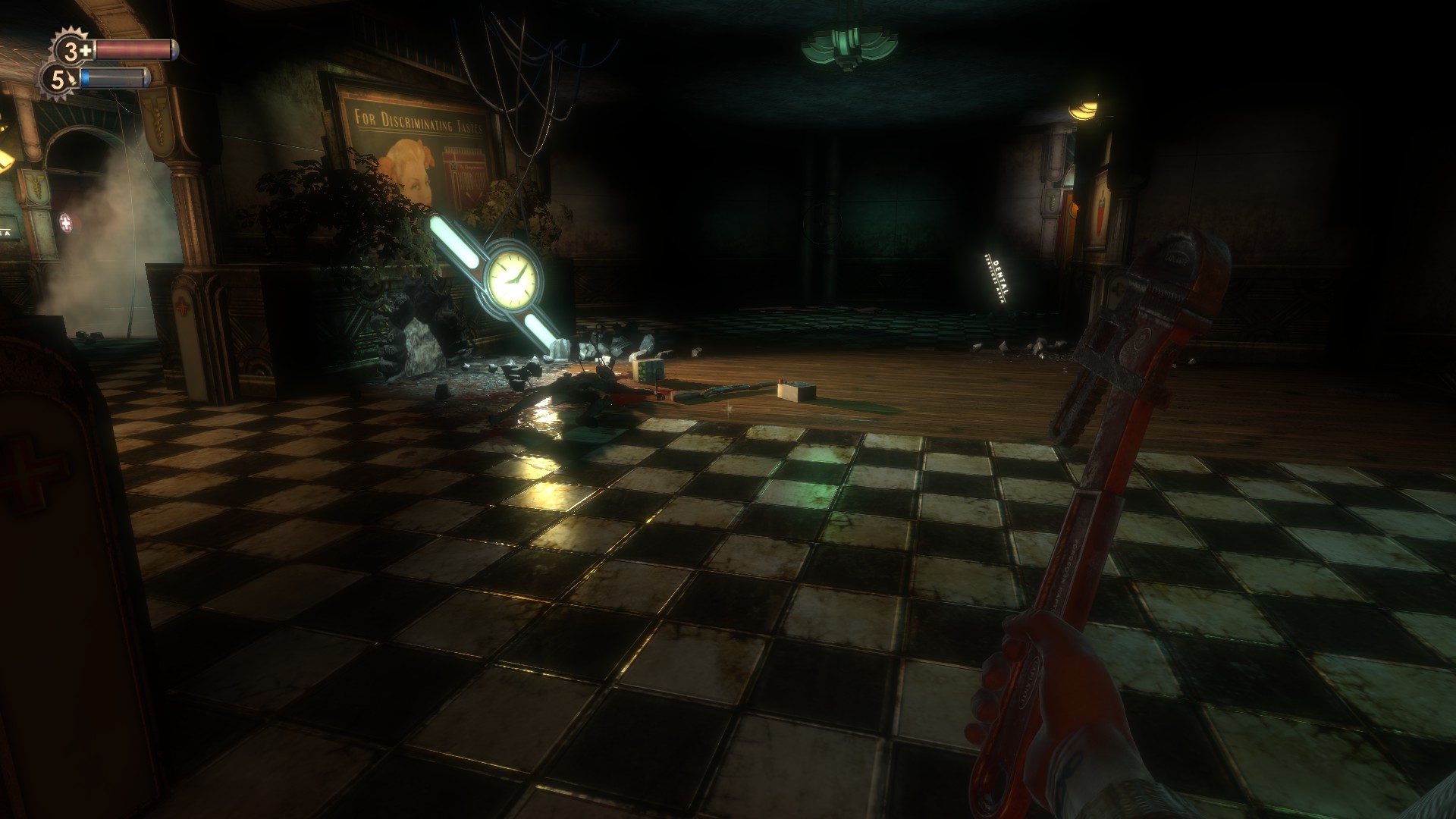

Bioshock established vulnerability in a number of ways. The game’s levels were dark, which is always nice and scary. Rapture was unfamiliar, and ominous signs and creepy sounds gave it a terrific ambiance. The splicers made Rapture feel like a city occupied by thousands of super-powered Jack Torrances. Much of the sense of vulnerability in Bioshock stemmed directly from its ambiance.

The open maps and planning-focused gameplay encouraged a cautious approach, especially where the tough and quick Big Daddies were concerned. The inventory system furthered the sense of vulnerability—Bioshock required scouring the environment for supplies, which meant that players could worry about not having enough of the right thing. In a game like Call of Duty, there's always ammunition to pick up; with Bioshock, there's a constant risk of running out. Ammunition types pushed this tension even further, introducing players to the worry that they might have plenty of ammo, but not the right type.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Bioshock used a bunch of little tensions to create one big sense of vulnerability. It sounded, looked, and felt threatening, and as a result, when we overcame a Big Daddy or a particularly nasty gaggle of splicers, we felt good about it. Modern shooters are focused on providing that sense of victory nonstop, but doing that robs victory of any meaning. With vulnerability, Bioshock gave its victories impact.

Consider Bioshock 2, a game which made the player a tough Big Daddy. Bioshock 2 improved on the combat, treated Rapture as if it was familiar, streamlined the world through linear progression, and removed the crafting and ammunition systems. It didn’t stick with us quite as much, despite having a really well-written story, clever call-backs and responses to the choices in Bioshock. Bioshock 2 could be seen as a better shooter, even a better game than Bioshock, but because players weren’t as vulnerable, their victories didn’t matter quite so much.

It was always about vulnerability, and Infinite never made players feel vulnerable. 1999 Mode makes weak players, not vulnerable ones.

Then along comes Bioshock Infinite, which streamlines things even further. It gave us a new world to explore, which was a plus, and initial reception was immediately positive, but in the months after its release, players began expressing their displeasure. Bioshock Infinite hadn’t learned the lessons of System Shock 2 and Bioshock. Rather than putting us in a new world, it merely showed it to us, keeping us at arms’ length.

It’s why I think Irrational’s attempt at 1999 Mode in Bioshock Infinite was so misguided. The “1999” seems to reference System Shock 2, but Infinite doesn’t feel like System Shock 2 or even Bioshock. Those games make us feel vulnerable in order to give us a sense of triumph. Irrational seemed to think that the complaints that Bioshock had been dumbed down related to difficulty, but it’s not about that. 1999 Mode makes weak players, not vulnerable. Vulnerability gives players long stretches where they worry about dying; it’s the feeling you get when you’re holding onto a rope that’s fraying. Weakness is what you feel when you die a lot, as you’re likely to do in 1999 Mode, given that your character has the constitution of wet tissue paper.

Rapture eternal

Victory has to feel earned rather than be an expected outcome. For shooters, providing players with a sense of vulnerability means that victories matter. Vulnerability adds weight and meaning to victory. A big flaw in recent shooter design has been the push towards power fantasy. Players become a Steven Seagal character, walking into a room, wrecking their foes with little thought or concern. Players have a lot more fun when they’re playing as Bruce Willis in Die Hard or Arnold Schwarzenegger in Predator. As players, we need the thrill that comes with earning our victories. We need to feel like what we did mattered.

When we walk away from an experience, what we have is the memory of the emotional roller coaster ride we went on. What sticks with us is how we felt about the game we played. For a game like Bioshock, vulnerability was a vital component, and Irrational built atop it as Rapture’s unnerving foundation. I walked into rooms worrying about whether I had enough items to survive. I left them feeling like a champion. It was a journey I took, one I made happen.

That, more than gunplay or story, is what sticks with us. It’s why we call Bioshock one of the best games ever made. We made memories down below the waves of Irrational’s virtual ocean. In making us vulnerable, Irrational gave us a world.