Action-RPG Elm Knight may be 30 years old, but it still feels like it's from the future

Much more than just a pretty bio-armour face.

Pasokon Retro is our regular look back at the early years of Japanese PC gaming, encompassing everything from specialist '80s computers to the happy days of Windows XP.

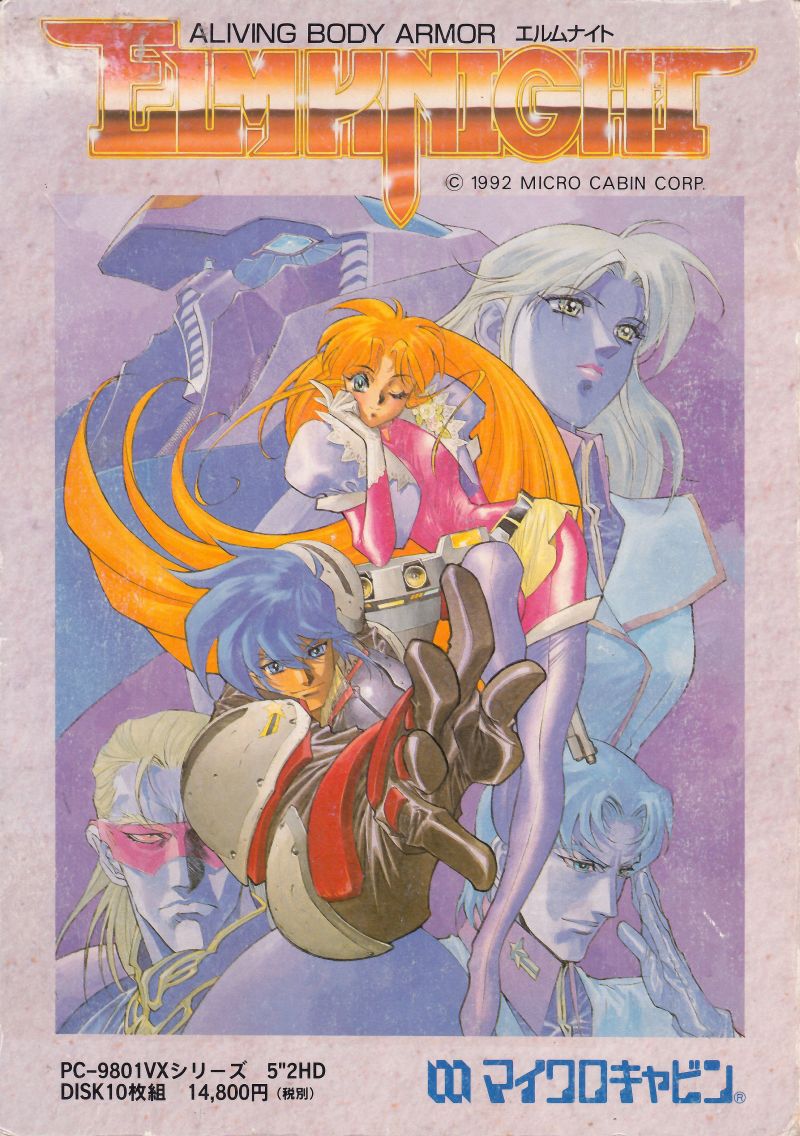

I'm a little ashamed to admit Elm Knight, a 1992 Japanese PC-98 action-RPG, caught my eye for the shallowest of reasons: a really cool title screen. Yeah, I know—absolutely disgraceful behaviour. In my defence, the title screen honestly is that good.

The image that grabbed me and refused to let go is a portrait of an inscrutable face, drenched in shadows. It's got a threatening but not necessarily aggressive aura to it, the figure staring out of the screen sculpted in that unmistakably '90s anime "bio-armour" style. It has a person-ish body that's not quite machine, but also definitely not birthed.

Even when I stop overthinking it, that single static image remains a great piece of pixel art, and I saw it as a guarantee that whatever I was about to dive into was going to look pretty good even if the rest of the game amounted to a miserable pile of nothing.

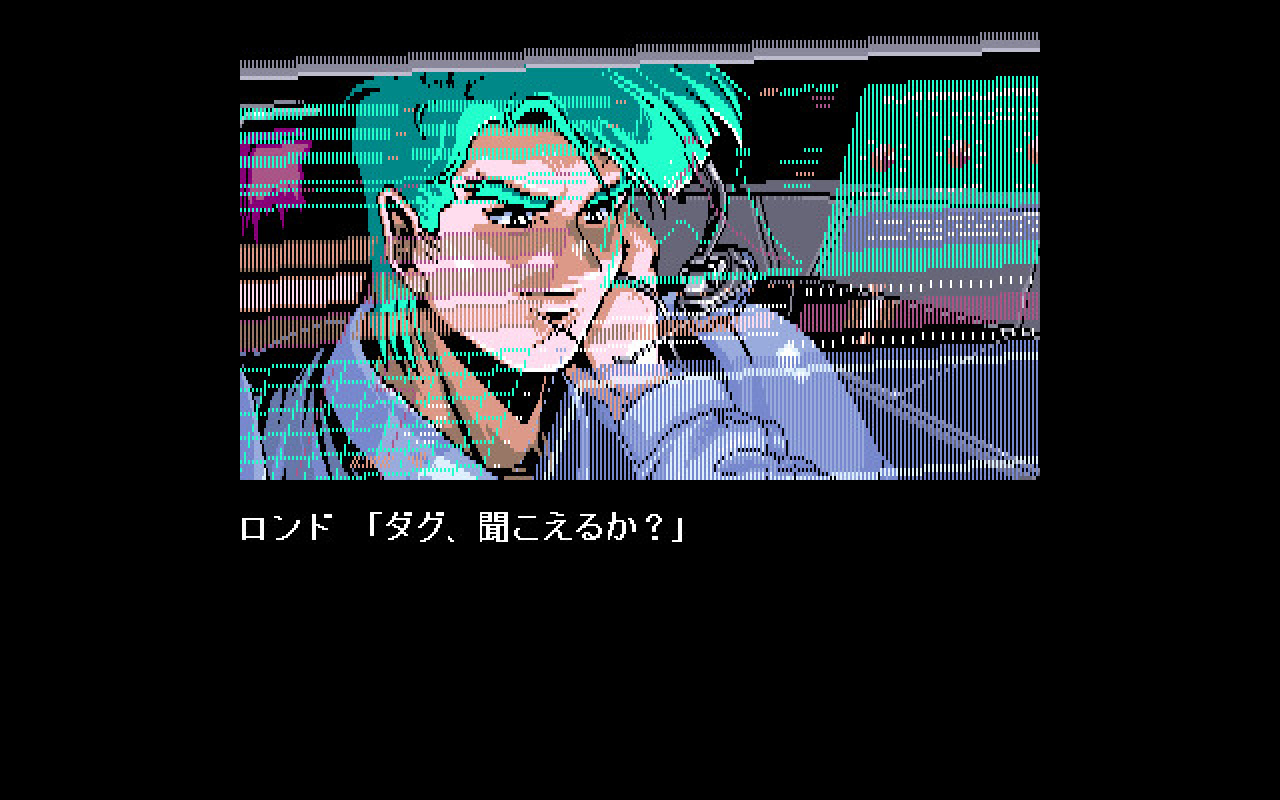

"Look pretty good" is something of a massive understatement for this 30-year-old game. Elm Knight is an astonishing 10-disk epic where magical "Irregulars" fight against the fearsome might of a tech-loving Empire, a game that opens with a lengthy animated cutscene and isn't shy about sprinkling the adventure that follows with even more. The frequency of these painstakingly hand-animated scenes is astonishing—no wonder the back of the box boasts about having two and a half hours of them.

The time and effort poured into these sequences shines through in every frame. Every single second of the intro is constructed in real-time using a combination of enormous action-packed sprites and scrolling background images. It displays animated cut-ins on top of continuously animated cutscenes without slowing to a crawl, a serious technical flex at the time—the steady stream of intensely detailed (and again, animated) mechanical designs make it feel like I'm witnessing a secret artist's battle, everyone on the team determined to out-do one another.

Somehow Elm Knight's artwork only gets better as the game goes on, casually introducing flourishes that few pixel art games would have for decades. There are animated "transparent" monitors and moving shadows that distort as they travel up and across other objects—handled manually by an artist's eye, rather than calculated by a graphics card.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Of course loads of computer games in the '90s had impressive cutscenes—I fondly recall sitting quietly in front of my Amiga as some moody chiptunes accompanied the finest pixel art Europe had to offer. But those cutscenes tended to make the rest of the game look a bit, well, boring. "Stage 1: START!"... and suddenly you'd be controlling some little guy who looked like their running animation had been outsourced to a deep sea fish who'd only had someone describe the concept of "running" to them over the phone.

This was happening in the same year Wolfenstein 3D arrived on English PCs

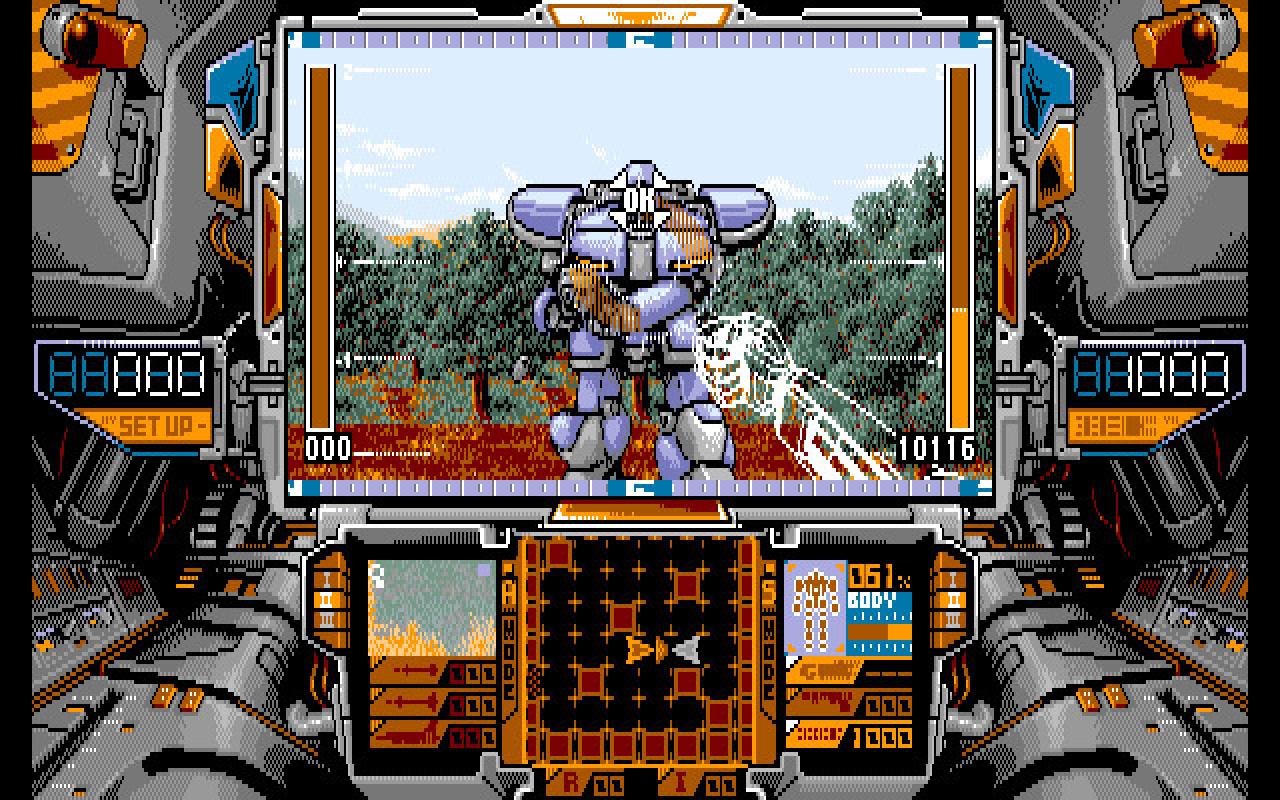

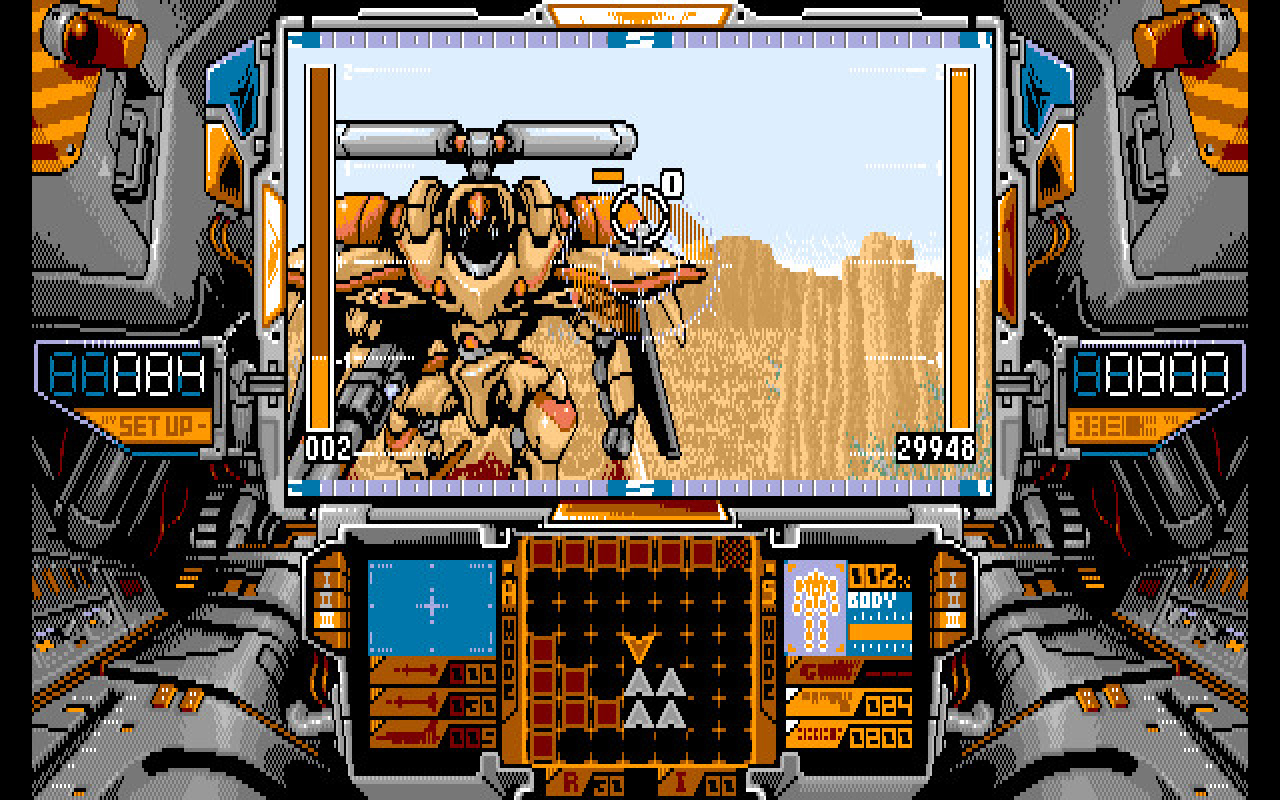

That's not true here, and if anything the parts of Elm Knight where I'm in control are where the real magic lies, thanks to Micro Cabin's "Space Graphic Structure" system (the fancy name for their proprietary 3D engine) used to bring real time first-person exploration and action-based battles to an old computer designed for neither.

Other games of the era like The Eye of the Beholder faked the effect, but Elm Knight has true seamless transitions from one "tile" to the next. Objects naturally grow larger as I step forwards or shift realistically (as far as a landscape made of scaled sprites can be "realistic") to the side as I turn or strafe.

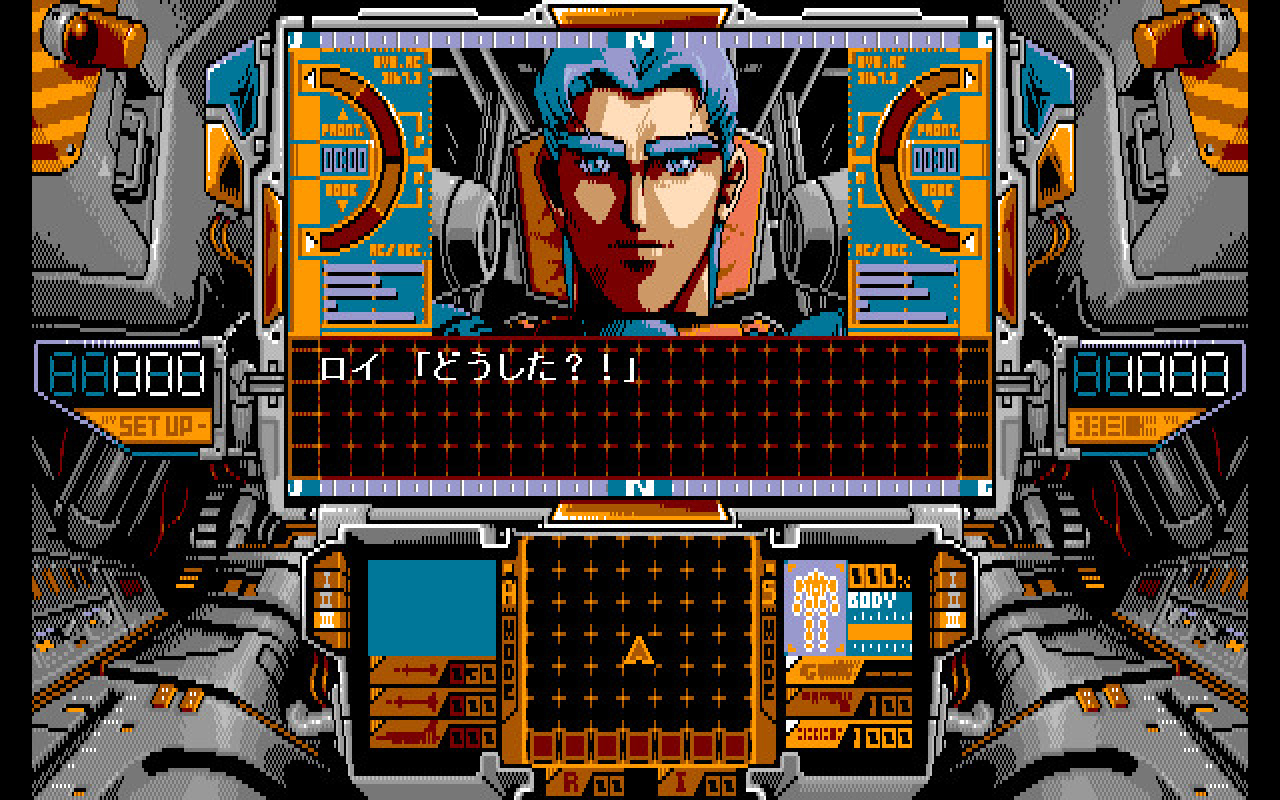

Of course there's always a catch with early '90s 3D, and in this case it's the enormous 2D overlay covering a large portion of the screen, used to disguise the reduced size of the playfield and keep the game running at more than four fps. Again Elm Knight is quick to do something clever and artistic: That's not a restricted field of vision, that's my character's point of view. In every mech-controlling segment of the game—and there's plenty of them—the pixeled frame is a cockpit, complete with functional instrument panels tracking enemy movement, ammo counts, energy levels, and more.

The cramped nature of this screen actually makes every piece of the cockpit feel even bigger than it would have if I'd had a wider viewport and a tidier interface. Elm Knight's presentation convincingly puts me in the shoes of a human pilot operating a towering bipedal war machine, rather than a player directly controlling a metal mech.

There's not a lot of time to soak in the scenery anyway, as during these segments I have to literally step out of the way of missiles fired at me by enemy mechs. Relatively open areas are designed around dodging, strafing, and sneaking in a cheeky shot before ducking back to safety (movement is handled via the number pad, because this was pre-WASD times). Ammo is generally in short supply, which means long shots at enemies facing the other way are a risky proposition rather than the safest and most sensible option. There are no cannon fodder enemies in Elm Knights.

I realise that in 2022 this all sounds about as "amazing" as voice actors speaking dialogue or a new FPS releasing with online matchmaking, but this was happening in the same year Wolfenstein 3D arrived on English PCs. At the time Elm Knight's 3D world would have been considered a huge technical achievement simply for existing, so it's especially remarkable to see Micro Cabin not only make it happen, but also do something worthwhile with its incredible graphics system once it was up and running. The end result is a game that plays like an exciting evolution of dungeon crawlers just a few years older than it—it essentially bridges the gap between the '80s Wizardry and the '90s Doom.

There's a tendency for games with this sort of technical prowess to adopt an overly simmy "no fun allowed" ethos—or maybe it's just especially rare for programming wizardry and imaginative design to go hand-in-hand.. But Elm Knight is silly from the jump, with its main characters often throwing light-hearted verbal jabs and comically goofy expressions at each other. A short conversation with an early NPC hammers the point home:

- "Hey! You'd better not be an Imperial spy!"

- "What? Of course I'm not a spy!"

- "That's something a spy would say."

It's a dumb joke, but it's also the perfect demonstration of Elm Knight's willful silliness, which sets up its more dramatic scenes to have a real impact.

Elm Knight is the complete package. Age has not diminished its achievements nor dulled its show-stopping moments, and beyond hoping for an English translation (official or otherwise) there is no real need for any alterations to what's already in there. It should be better known for its killer art and raw ambition coming together to create a technical showpiece.

Clearly I'll have to play games with cool title screens more often.

When baby Kerry was brought home from the hospital her hand was placed on the space bar of the family Atari 400, a small act of parental nerdery that has snowballed into a lifelong passion for gaming and the sort of freelance job her school careers advisor told her she couldn't do. She's now PC Gamer's word game expert, taking on the daily Wordle puzzle to give readers a hint each and every day. Her Wordle streak is truly mighty.

Somehow Kerry managed to get away with writing regular features on old Japanese PC games, telling today's PC gamers about some of the most fascinating and influential games of the '80s and '90s.