Our Verdict

Even Abermore's cult of beetle worshippers would draw the line at this many bugs.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A standalone version of a Thieves Guild questline from an imaginary Elder Scrolls game.

Expect to pay: £12.99/$15.99

Developer: Four Circle Interactive

Publisher: Fireshine Games

Release date: Out now

Reviewed on: Windows 10, AMD Ryzen 5 5600X Six Core CPU, 16GB RAM, Nvidia Geforce RTX 3060

Multiplayer? No

Link: Steam page

In the dead of night, a local busybody comes straight to the door of your flat with gossip. Evidently, there's no Facebook in Abermore. "The puddle's back," he says. This pool of liquid sits on the city's thoroughfares, apparently, and looks normal enough at a glance. But when carriages pass through, it doesn't splash. And while reflective, it never shows an image. Residents suspect it's fathoms deep. Oh: and that anything falling in turns to metal.

"Transports itself across the city, coming and going as it pleases," says the busybody. "It's a small patch of wrong."

If only there were just one small patch of wrong in Abermore. Somewhere below the surface of this game, there's a perfectly charming heist simulator that channels Thief and Skyrim's Dark Brotherhood quests. But it's drowning—not just in puddles, but oceans of wrong.

I could tell you that Abermore is buggy. Or I can tell you that I was awarded the Steam achievement for clearing a level without causing a disturbance—before I'd set foot in any level. That I couldn't enter the first mission because the mouse cursor was glued fast during the introductory dialogue. That, after hitting Alt+F4 to boot up Abermore again, I inexplicably won another achievement, for equipping a new outfit. That, once inside that mission, the first NPC I encountered immediately succumbed to a recurring loop—flailing endlessly at the lever of a mansion's reporting station after jumping at the noise of my footsteps. Those opening minutes were sadly indicative of what was to come.

Hoodwinked

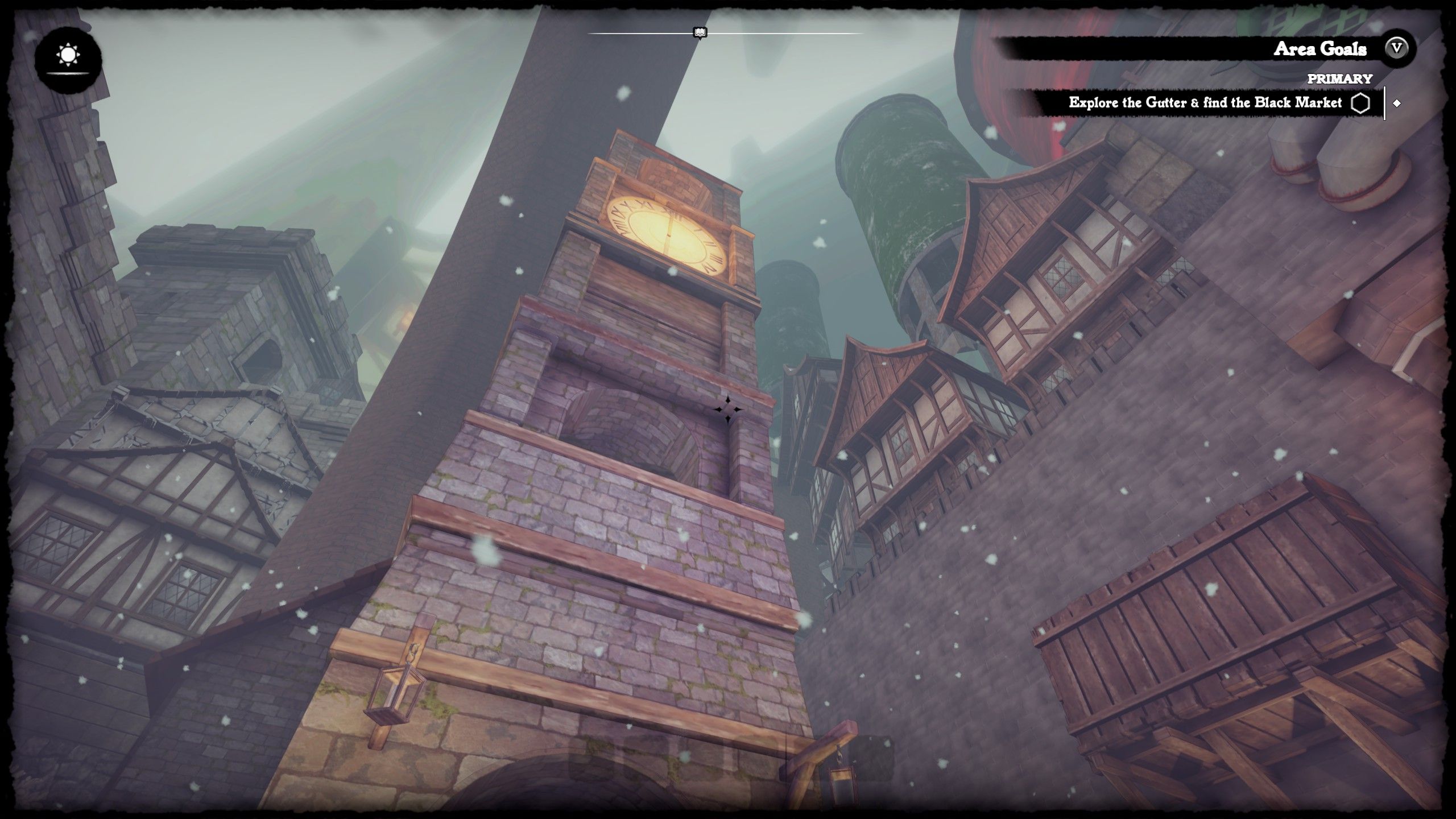

There's nothing wrong with the premise. Abermore casts you as a street rat in The Gutter, the lowest level of a vertiginous, medieval-industrial metropolis that roughly resembles Edinburgh at a steampunk convention. After your Robin Hood-esque leader is captured and imprisoned, you and your fellow conspirators plot a grand jailbreak, to take place during the Feast of the Lucky Few: an eclipse celebration that doubles as a gross demonstration of wealth inequality. Hopefully you'll be able to nab a few fancy goblets on the way out to make the point.

At the beginning of the game, the feast is a couple of weeks away. And so, each night, you take on a smaller job for a local ne'er-do-well: clearing a stately home of its valuables to get some practice in, fund better equipment, and increase your reputation among potential collaborators. There's a satisfying sense of procedure to this setup: rolling out of your bed at noon, pottering around a petite hub to pick up side quests, and then sliding into the underground pub where thieves gather in the evenings. There you'll sell your ill-gotten goods to the fence, pick ability-boosting tarot cards, and decide on your job for the night. There's a touch of Atlus-style life simulation involved as you get to know the regulars, win their trust, and ultimately pin them down to help out on the night of the Feast.

It's out on the job that the problems really start to stack up. There's a random element to levels, designed to keep them fresh. While you might recognise the layout of a locker room or lobby here or there, these rooms slot together procedurally. But none-too-effectively.

It's as if every house were a Clockwork Mansion in need of a watchmaker's attention. Some rooms have invisible walls, blocking movement unexpectedly; others are missing floors, leaving guards and consumables stranded in midair. It's very common to scale a staircase and notice an airy gap between two floors, making the positions of guards and butlers visible from above. At worst, gaping holes in the architecture leave buildings open to the elements—a far bigger security issue than me and my lockpicks, and an insulation nightmare to boot.

Sneaking around these splintered spaces is, at least, a fundamentally sound experience. It's a matter of secreting yourself into crawlspaces, under tables, and onto rafters—essentially becoming insulation yourself to avoid being seen by staff or security cameras. In this way you gradually map the building, casing for gems and rare whiskey and thinking up creative ways to bypass busy corridors.

Tools of the trade

The latter challenge is enhanced by a crafting system that allows you improvise lockpicks, sleep darts and explosives on the fly so long as you have the recipe, and can source the materials among your mark's belongings. More than once I fashioned a solution to a problem I would otherwise have given up on, preventing me from heading home sullen and empty handed.

It's rare an object is just one thing; a banana provides health, but a banana skin is a trap. There's a pure, early YouTube pleasure to watching the house's master slip and knock himself unconscious after responding to a service bell rung by yours truly. But it's undermined by AI that's unresponsive and shortsighted—a little too forgiving to make you feel truly vulnerable. That said, things fall apart fast when complacency leads to discovery. Suits of armour spring to life, gas rises, and the objective becomes secondary to finding an exit fast.

Over time, I learned to circumvent not just butlers and cameras but Abermore's many flaws, and found myself half-enjoying the game it could have been. But there's simply no way to recommend an experience that might include falling through the floor, or getting stuck on a broken dialogue screen that forces you to replay an entire day of hub conversations and inventory management. Not even when that dialogue is goofily good-natured, showcasing clammy vampires, open-carry swordsmen, and overexcited scientists stuck in quicksand. And not even when that hub is beautifully accompanied by church bells and a tailor who operates his sewing machine in time to stabs from the soundtrack's pipe organ.

I still want to belong to this psychotically daft twilight world, where the fence lets out an admiring "hooo!" as you slide a particularly big gem across the table, like a host on Antiques Roadshow. But the puddles are too many, and they're fathoms deep.

Disclosure: Former PC Gamer Deputy Editor Philippa Warr contributed to Abermore.

Even Abermore's cult of beetle worshippers would draw the line at this many bugs.

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.