A woeful errand through pixels and music in Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP

Not one of the great PC indies. But a great indie game that’s on PC.

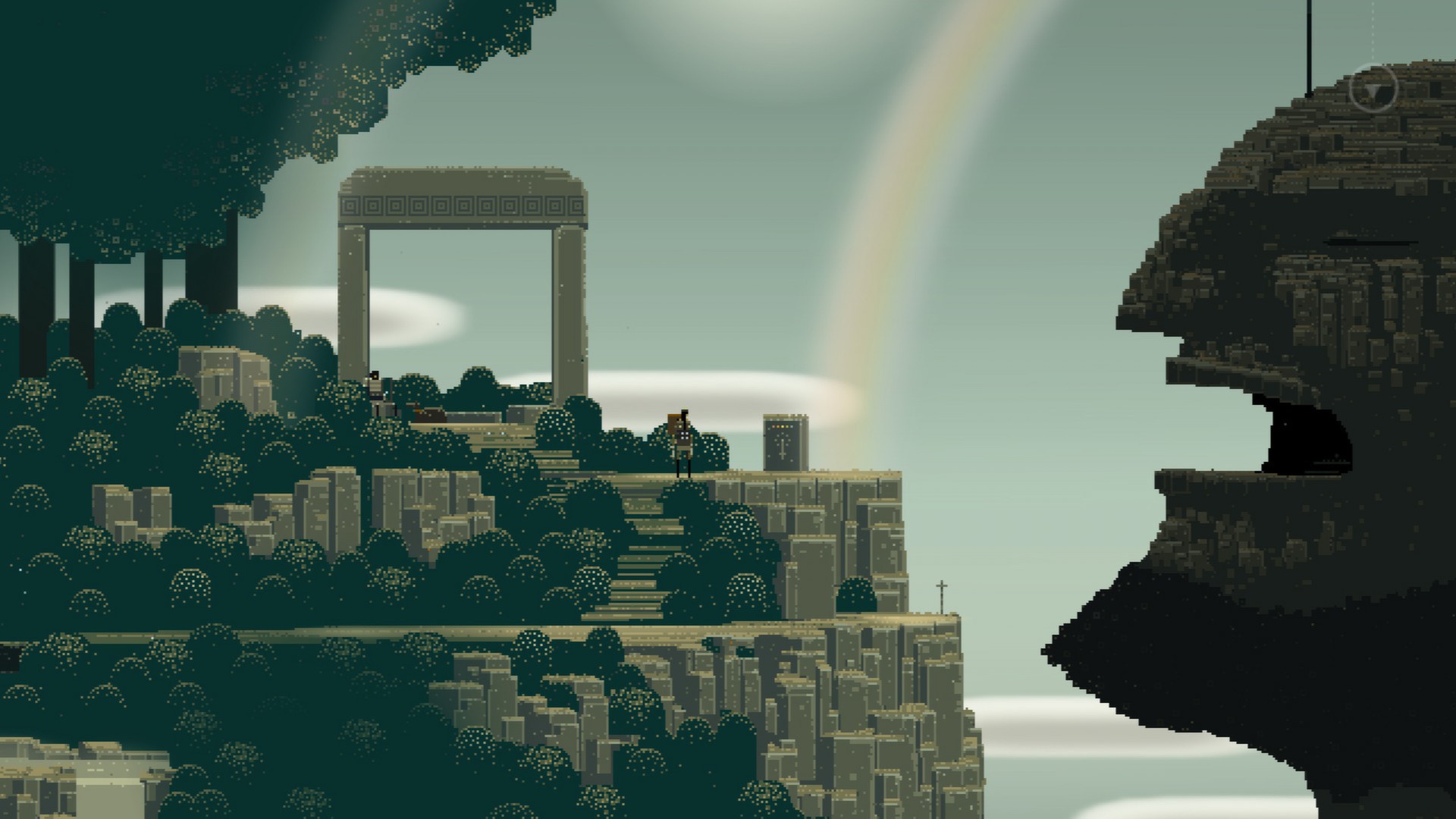

Sword & Sworcery EP wants you to lose yourself in its world. At its most effective, it creates an unearthly atmosphere that lodges itself in your subconscious to the point that, years later, you might catch yourself remembering its gloomy landscapes, or haunting music. I’ve thought about it a lot in the five years since I first played it. On that basis, it remains an affecting and mysterious success.

I’d love nothing more than to praise the mood of what is essentially a collaborative art piece masquerading as an adventure game—and I’m going to spend plenty of paragraphs doing so. But, replaying it now, I can’t help but notice how ill-fitting the game can feel on PC. Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP was originally made for iOS, and it shows.

Instead of clicking, you’re instructed to ‘tip tap’ on the screen. Instead of dragging, you’re asked to ‘tap and hold’. But it’s not just the verbs that feel out of place. Much of Sword & Sworcery’s puzzles rely on the tactile connection between the world, its music and your fingers. The pleasure is in playing with the environment, and, while that does come across in its biggest, most spectacular moments, many of the more subtle interactions feel rote when performed with a cursor.

Many iOS games do carry their spark over to PC, but Sword & Sworcery is more experimental, and so some elements are lost in translation. This is, after all, a game that lasts for around three hours, but that will take you a full lunar cycle to play. It’s weird and indie—in the truest, most Beck sense of the word.

It opens with the Archetype, a representative of Superbrothers, and the Dante of this world. The Archetype introduces each chapter, breaking the fourth wall to frame the story proper. More generally, the Archetype is a statement of intent with regards to Sword & Sworcery’s style and mood. Once briefed on what’s to come, you take control of the Scythian—a warrior who has travelled to the Caucasus Mountains to complete her woeful errand.

The most notable things about Sword & Sworcery are how it looks, how it feels and how it sounds, and later, as the woeful errand approaches its conclusion, how these elements intertwine to create something arresting. The environments are simultaneously detailed and sparse—strange, eerie and beautiful, and reminiscent of ’80s Amiga platformer Another World. This is no coincidence. Back in 2010, a year before Sword & Sworcery’s iOS release, Superbrothers’ sole member, Craig Adams, wrote a manifesto for the site Boing, Boing.

Called Less Talk, More Rock, the manifesto is, in part, a statement of intent with regards to what Sword & Sworcery would be. Its ‘hall of fame’ is a list of games that adhere to Adams’s philosophy, and so likely influenced Sword & Sworcery in some way. It’s a varied selection, containing everything from Another World and Demon’s Souls, to Rez and Motorstorm: Pacific Rift.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The ‘Less Talk’ refers in part to the creative process. “Maybe you get lost in all that talk—all that intellectualising, all that ‘what if?’,” Adams writes, “all those numbers and sales projections or what-have- you, all that self-doubt—and you lose your way.” But ‘Less Talk’ also applies to the writing within games. Adams goes on to praise Zelda’s sparse, dialogue—such as the iconic: “It’s dangerous to go alone. Take this.”

“When there’s just a little bit of talk like this it has a peculiar, haunting, poetic effect,” he writes. “It tickles the intellect just enough for it to stir, but not enough to irritate it.”

This philosophy is found throughout Sword & Sworcery. Every segment of dialogue comes in at under 140 characters. As the Archetype explains, “Our research indicates that social support networks will play a significant positive role in the outcome of Sword & Sworcery EP.” I disagree. The game’s social integration made slightly more sense in 2012, before Twitter was a garbage fire of hot takes, but even then not a lot.

The Scythian is part mythological warrior, part beatnik. “To the mountain folk of The Caucasus he was known as ‘Logfella’ and he seemed cool,” she says of one of the game’s few main characters. “Logfella knew all about our woeful errand and he agreed to lead us up the old road. Still we definitely got the feeling that he wasn’t super jazzed about this.” The Scythian’s colloquial musings fit well within Sword & Sworcery’s whole ethos, reinforcing its tone and thus strengthening its best moments.

The true hero of Sword & Sworcery is its music. Jim Guthrie’s folksy electro soundtrack is the heart and soul of the game, providing depth and texture to the world. It makes itself known early on, as the Scythian, Logfella and Dogfella (a dog) journey to the mountain Mingi Taw backed by the wonderful song Lone Wolf. Later, while exploring the forest peoples’ dream world, the Scythian meets Guthrie, and is invited to sit as he plays a tune on his guitar. The Scythian, versed in the musical magic of Sworcery, can join in, using the trees as instruments to jam along. It’s a beautiful, contemplative moment.

The bulk of Sword & Sworcery’s puzzles involve looking around the screen, clicking on bits of scenery to summon a sylvan sprite. Collect enough, and you can trigger a time of miracles—summoning a triangular piece of the Zelda-like ‘Trigon’. You’ll click on some owls. You’ll click on some sheep. You’ll strum a waterfall like it was guitar strings. This is Sword & Sworcery at its weakest, at least on PC. These interactions are playful, but rarely feel engaging. The soundscape maintains a specific mood, though, even when you’re trying to work out the correct order in which to click on some trees.

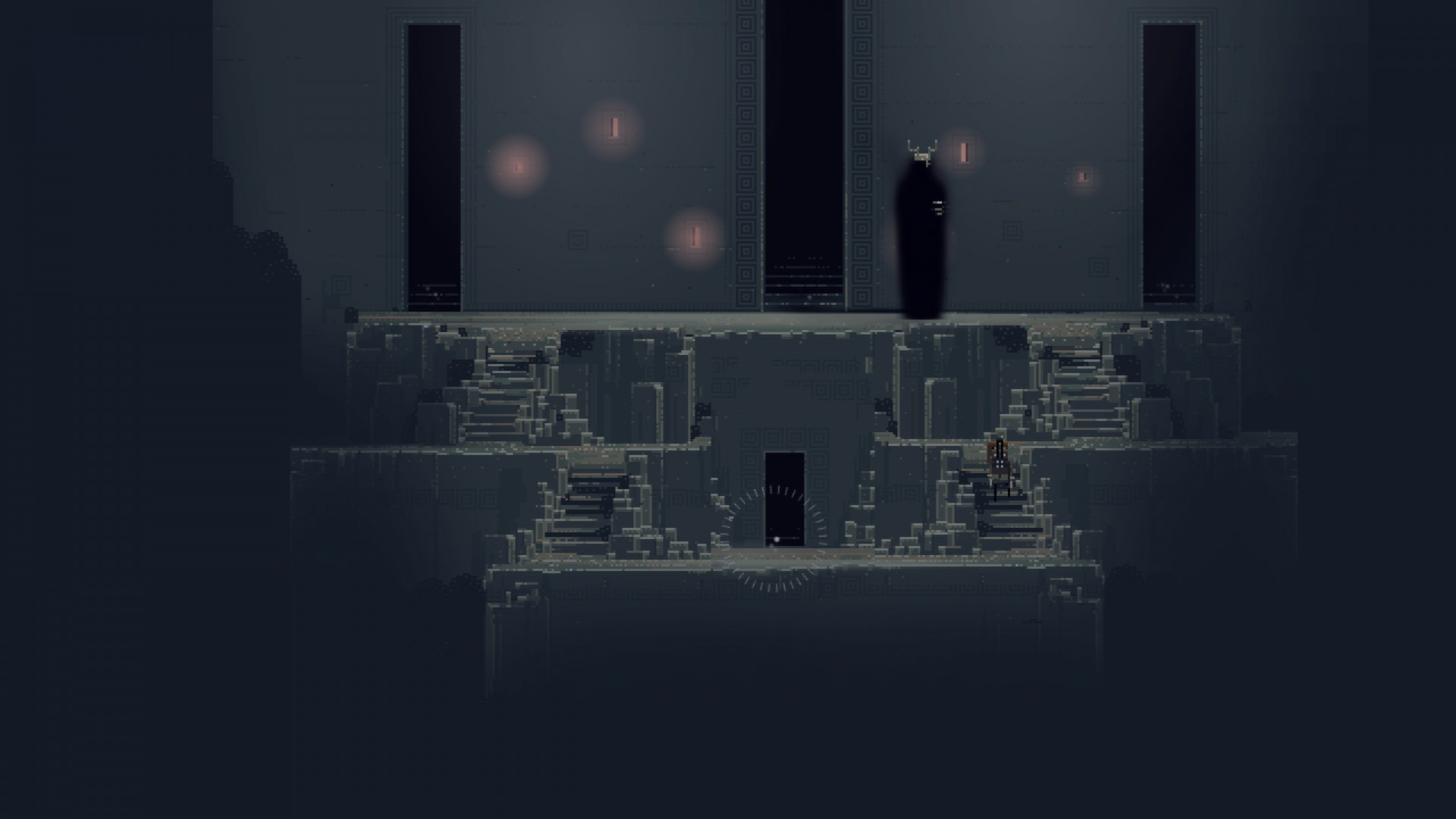

Around these more mindless sections, though, Sword & Sworcery is fun to interact with. Its battle system works well. It’s simple—you click on the sword or shield at the correct moment—but the fights have a rhythm action quality, and enemies will telegraph their attacks with driving beats against their shields. It sounds great. Particularly good are the battles to tame the pieces of the Trigon. These are protracted, multistage boss fights, set to a dark and pulsing song. It makes the mythology of the world feel wild and unsettlingly anachronistic.

One of Sword & Sworcery’s most experimental tricks is how it uses the phases of the moon. As the Archetype reveals, “This session typically requires a lunar month to complete.” That’s because the dark and light Trigon will only appear on dates when there’s a new or full moon. This is another element that feels a out of place when played on PC—a device that you can’t carry on you at all times. Still, I like the commitment to the concept. And if you can’t be bothered to wait, you can fight a naked boar guy for the key to a secret room that lets you control the moon.

Sword & Sworcery isn’t one of the great PC indie games. But it is a great indie game that’s on PC. Many iOS ports feel more suited to desktop, but, even despite its problems, Sword & Sworcery remains a memorable and enchanting experience.

Phil has been writing for PC Gamer for nearly a decade, starting out as a freelance writer covering everything from free games to MMOs. He eventually joined full-time as a news writer, before moving to the magazine to review immersive sims, RPGs and Hitman games. Now he leads PC Gamer's UK team, but still sometimes finds the time to write about his ongoing obsessions with Destiny 2, GTA Online and Apex Legends. When he's not levelling up battle passes, he's checking out the latest tactics game or dipping back into Guild Wars 2. He's largely responsible for the whole Tub Geralt thing, but still isn't sorry.