Moirai was one of the PC's most disturbing games, and now it's gone forever

A look at one of the strangest online social experiments in recent memory, now lost to time.

It used to take about ten minutes to finish Moirai. By all appearances it was a short, narrative-driven adventure game—something small and unremarkable made in a weekend game jam. But there was more to it than that. There was this, for instance: Once you’d completed it, you were never meant to play it again.

You could play Moirai again if you wanted to, but its impact was vastly diminished. Some people probably did a second run to make amends, because they hadn’t taken the game seriously enough the first time round. Or they played it again because they wanted to test its boundaries, or to get something off their chest. Oddly enough, there was a small community who actually played Moirai over and over again.

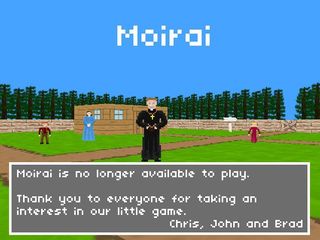

Moirai used to be one of the weirdest games on PC, but due to sustained attacks on its database—not to mention in-game abuse—it’s now gone forever. Designer Chris Johnson announced in June that he's pulling the game from all portals (Steam, Itch.io, GameJolt) due to a scripting hack which flooded the game with obscenities. To someone who never played Moirai, or has never even heard of it, it's hard to understand why a pixelated, 10 minute indie game would attract that kind of attention, that level of trolling.

But it did, and the people who played it know why. It’s because you could, in a minor but very effective way, define the game for the very next player in line. Moirai was a “continual cycle of death”, and it was up to you to decide what kind of mood the next player would die or survive in.

The Cave

Since Moirai is gone forever, you’ll have to allow me to explain the whole thing from scratch.

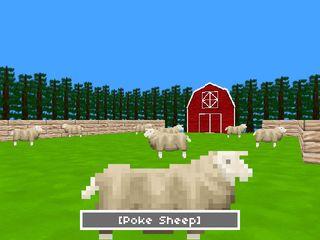

You spawn in a small, square, pixelated township. There are four blocky houses and a handful of townspeople. The graphics are reminiscent of a Minecraft knock-off: low-res textures, functional, spartan. They’re ugly really, but in a low-key whimsical way that puts you off guard and makes the ending more eerie.

Exit the township and you’re on a farm populated by sheep (you could kill these sheep, and doing so was popular, naturally). Over in the far north-western side of this farm there’s a lumberjack guarding the mouth of a cave.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

“My brother and I were chopping wood when we heard moans coming from the cave,” the lumberjack explains. “My brother went to investigate.”

The lumberjack is worried: his brother should have been back by now. Inevitably you enter the cave with a lantern in order to check what’s happened. Once in the cave—a network of thin tunnels and cavernous square rooms—the lumberjack’s brother appears.

“The moans are coming from further down,” he says. “I’d go in but my sight’s no good.” The lumberjack’s brother gives you a knife. “Who knows if you may need it.”

At this point, first time players might assume that they’ll be slaying demons or monsters with said knife in the not-too-distant future. Who knows: they might even find a gun! There are three routes to go—left, right and straight ahead – and the first problem is deciding which way to go. Down the left side there’s a room containing bones, apparently belonging to a child, and a hole in the wall with something shiny just out of reach. Down the right tunnel, there’s a room with lots of cross-fives etched into the wall, as well as a tool with which the etchings were done.

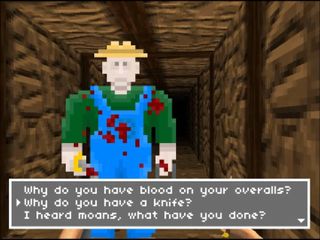

Inevitably you go down the centre tunnel, because there will probably be something to kill down there. And there is, of course: a blood-spattered farmer. But rather than grind him to dust with your pathetic little knife, you have the choice to ask him some questions, let him pass, or kill him. And this is where the game starts to get weird.

You’re prompted to ask the blood-spattered farmer three questions: Why do you have blood on your overalls? Why do you have a knife? I heard moans, what have you done? You’re able to let the farmer pass, or you’re able to kill him.

The twist is that the answer to these questions—the answers delivered by the blood-spattered farmer—are entered by the last person to play the game. The gravity of this moment will depend on whoever played the game just before you.

Later on, you wander further down the central path, only to find a dying woman. “I came here to end my life,” she says. “My name is Julia and I want to see my child and husband in heaven.”

After a monologue, she asks you to kill her. You can choose to kill her, or else you can choose to go for help, but if you choose the latter, she spits blood at you in a rage. On your way out of her cave you’re held up by another farmer, who asks you the exact same questions you previously put to the blood-spattered farmer.

Once you’ve answered them, however you see fit, the game is over. “Let me see what is to be done with you,” the farmer says in closing.

Then later on, you get an email. This was mine:

Behind the scenes

“From most players’ perspective, when they run into the person in the cave for the first time, they think of them as an NPC, not an actual person,” Moirai designer Chris Johnson told me over the phone from Adelaide. “I think there’s an interesting element in that. There’s a certain codified language about how people approach games, and one of those things is that most of the characters you’ll interact with will be some pre-programmed thing, unless the game is explicitly a multiplayer one. I thought it was an interesting thing to subvert that expectation: you don’t realise the other player is actually a player. You see them as an NPC.”

Moirai was created by Johnson, Brad Barrett and John Oestmann, as part of the 2013 7DFPS gamejam. It wasn’t finished by the time that jam ended, so the trio finished it over the course of several months in their own time. Inspired by an experimental, interactive theatre piece by Belgian group Ontroerend Goed—in particular the second part of that trilogy entitled A Game Of You—the game was not the type you’d expect to attract lots of players. A lot of people might balk at the idea of calling it a “game” at all.

As soon as you start up Mario you want to see how high he can jump. In some ways [being offensive] is the equivalent for Moirai.

“We weren’t really sure what to expect,” Johnson said about Moirai’s eventual viral spread. “At the time we hadn’t released something before, so we didn’t have the background to judge how popular it could be, nor what that actually means. On top of that, we knew that this was different and that we couldn’t evaluate it under the normal conditions you’d evaluate these things.”

The game existed in relative peace for a while. When Johnson posted a post-mortem months after the game’s first release in 2013, a total of 10581 playthroughs had yielded some interesting results. While most players (around 88%) asked all three questions before deciding whether to let the blood-spattered farmer pass or to kill him, 52% had used ban-able words in their playthrough. In other words, people liked to be nasty in the game. A lot.

That was naturally exacerbated when Moirai launched on Steam in 2016. It found a much bigger audience than ever before, though Johnson stopped taking stats because he needed to clear the database regularly in order to avoid overload.

“I was surprised by that,” Johnson said of the surplus of toxic entries. “I think I was a little bit naive. Part of the problem was that the secret of the game was known by a lot of people—we had people like YouTuber Markiplier play it—and it was pretty popular on YouTube. People would go in there and pretend to be Markiplier, or just post horrible things.

“Some of that comes because it’s a free game and a lot of people who played it are kids,” Johnson surmised. “The other side of this, is that what naturally happens is people want to push the boundaries of the rules. As soon as you start up Mario you want to see how high he can jump. In some ways [being offensive] is the equivalent for Moirai. [People ask] ‘if this game is real and serious, and the promise is that I can enter whatever I want, then I’ll put a bunch of profanity in there and see whether I’m allowed to do it’.”

Down the right-hand path, the player encounters a room etched with cross-fives and a book on a pedestal. These markings track the amount of times the game has been played, while the book itself lists the names of the last five people to play the game.

Often, people would assume that the objective of the game was to memorise and repeat whatever the last person had entered, ie, whatever the blood-spattered farmer had said only minutes before. Where there’s no hard-and-fast or familiar game-centric rules, a player will sometimes try to make their own. Others would turn the game in on itself, creating a whole new meta-game within the game. “For example there was one player who said ‘if you like PlayStation, kill me, if you like Xbox, let me pass’,” Johnson remembers.

“Or there were some people who, once they realised what was going on, were really clever and added additional story elements. That creativity was really interesting too.”

Of course, many used it to distribute toxic, racist, hateful remarks to whoever was unlucky enough to play after them. Johnson wasn’t aloof to any of this. The emails sent out by Moirai to each player had a reply-to which directed straight to Johnson’s personal email account, so he’d often be emailed by players unaware that someone would be on the receiving end.

“Sometimes people say thanks very much for the game,” Johnson said. “I’d get five to ten emails a week like that. But sometimes I’d get horrible responses back. Someone might write back ‘faggot faggot faggot’. And this is the thing – it’s terrible to say, but in a lot of cases these are children.”

Since Johnson has a background in teaching and felt some responsibility to enlighten these miscreants, he’d spend most of his long bus commutes to-and-from work replying to the toxic emails on his laptop. “[I’d tell them] I’m actually the game developer behind this game,” Johnson said, “and not the previous player. I’d tell them I don’t think that’s an appropriate way to respond.

“And the person replying would say, ‘oh, I didn’t think anyone would receive this’.” They thought they were just swearing into a void.

The End

In late June, Johnson posted on Steam that the game was coming to an end.

“Since launching on Steam our database has received several attacks. We’ve worked hard (and sometimes with supportive community members) to update our system to a more manageable state and minimise the likelihood of attacks.”

It continued: “However recently our database was under a repeatable attack that ruined the game experience for a few players and resulted in it going offline. It’s important that you know that no email data was compromised in this attack. However this vulnerability means that we are subject to future attacks. We’re not a large studio and we don’t have the resources to properly prevent against these attacks so we’re going to pull the game from the store.”

Moirai connects directly to a database which stores player’s responses. From this database the game retrieves only the data it needs for a playthrough, ie, the last player’s responses and the provided names of the last five players. One user had written a script which would continually insert records into this database, not only rendering the game unplayable—all responses within that period would have been the same—but also crashing the database.

Moirai tested both your reaction to some hairy moral dilemmas, while also, secretly at first, testing whether you can react without being a dick.

Johnson knows how to stop this from happening, but he has neither the time, money or resources. The person responsible for the script later messaged Johnson on Steam, which lead to a long exchange. When asked why they’d overloaded the database, they simply replied “bc I thought it was funny.”

“For the lulz eh,” Johnson replied.

“You bet my man,” the script writer replied.

Later Johnson asked the script writer what they thought of the game. “I thought it was interesting, and that the camera and fog made it feel eerie,” they replied. “The positioning of the camera, the slow speed of the player, makes you feel vulnerable.”

Chris did make an effort to explore better options than taking the game down permanently. “I contacted Valve a week ago about retiring the game and exploring possible actions to take against the attacker,” he wrote to me in a follow-up email. “The game was retired reasonably quickly, however I haven’t heard a word from them in response to the attacker.”

Overall, he’s disappointed but not too shaken. He intends to help build an offline version of the game to aid speedrunners, but it won’t be designed for normal play. “It’s disappointing but I feel okay about it,” he said.

“The response from players completely exceeded our expectations so in that regard we’re quite content. The outpouring of support we received from the community after announcing the games retirement has been very heartening.”

It’s an interesting—albeit disappointing fate—for a game that tested the way we morally engage with what we play. Often morality in games is statistical: do a certain number of good and bad things, and get the corresponding result. Meanwhile, morals are usually demonstrated as part of a narrative, not as part of a system. When moral is tied to narrative, a game’s creator is usually in some fashion describing or teaching or prescribing a moral.

That wasn’t true in Moirai. It really just forced you to assess yourself: how you comport yourself when you think no one’s listening. It tested both your reaction to some hairy moral dilemmas, while also, secretly at first, testing whether you can react without being a dick. (That’s me being moralistic, sorry).

“Usually at the point where people are typing something in... hopefully they’ve had the realisation about what’s going on,” Johnson said. “At that point a lot of people might reflect on their previous decision to let someone pass, and think ‘well, actually, the choices that I’m making here do matter’, to the extent that they matter at all in a game. Or at least, [the decisions] have more impact than they initially thought.

“But also there’s this other aspect of [the player] hopefully realising that whatever they type in, they’re still sort of powerless to influence the response of the other players, the next player, who comes in later to decide their fate. There’s a kind of vulnerability there.”

Shaun Prescott is the Australian editor of PC Gamer. With over ten years experience covering the games industry, his work has appeared on GamesRadar+, TechRadar, The Guardian, PLAY Magazine, the Sydney Morning Herald, and more. Specific interests include indie games, obscure Metroidvanias, speedrunning, experimental games and FPSs. He thinks Lulu by Metallica and Lou Reed is an all-time classic that will receive its due critical reappraisal one day.

Most Popular