2022 has been a year without games. That's one of the more common refrains that's circled around the Internet this year. Obviously, this assertion is as incorrect as it is unfair. 2022 has seen tons of fantastic games. Medieval murder mysteries, spectacular automated roguelikes, rhythm-based FPSs, FMV erotic thrillers, diminutive survival games, and countless more.

But it is true that a certain type of game hasn't really happened this year, namely the glossy, expensive blockbuster. Out of the handful of new big-budget games that were released on PC in 2022 only one, Elden Ring, managed to break a score of 90. Beyond that, it's slim pickings. Modern Warfare 2 was decent, I suppose. A Plague Tale: Requiem was kinda in the realm of blockbusters if you squint at it in the right light. PlayStation owners can brag about Horizon: Forbidden West and God of War: Ragnarok, but even putting aside the fact they didn't come out on PC, two major console exclusives in an entire year is not exactly a strong hit-rate. That said, it's stronger than Microsoft, whose only new first party release was *checks notes* Pentiment.

Then we had the miserable disappointment that was Saints Row, while Gotham Knights was similarly a fart in a catsuit. Dying Light 2 also happened. Chris liked it. I most definitely did not. The end of the year has been slightly stronger, with Darktide and the Callisto Protocol providing some expensively grisly spectacle, though both launches were hampered somewhat by technical issues.

We all know the reason for this dearth of blockbusters. It begins with a "P" and ends in "-andemic". The delayed effect of Covid-19, which forced many studios to adapt to a work-from-home model, has had a significant impact upon schedules. As a result, a bunch of games pipped for 2022 have slipped into 2023, including Starfield, Redfall, Suicide Squad, Forspoken, to name but a few.

Yet while the pandemic has exacerbated the issue, it's not exclusively to blame for 2022's meagre offering. If anything, the pandemic has served as a handy scapegoat for more systemic issues in the games industry. Making big games is becoming ever-more demanding, and developers are increasingly unwilling to put up with the bullshit involved.

To demonstrate this, let's consider what a big-budget game in 2022 looks like. The industry standard is a vast, intricately detailed open world that provides dozens, if not hundreds of hours' worth of experiences. It needs lifelike characters, multiple fully realised towns and cities, an exquisitely animated platforming system, a combat system that can keep players entertained for countless hours. It needs a story that'll include hundreds of thousands of words of dialogue, and hundreds of hours of voice acting. It'll probably have a stealth system, and a crafting system, and some pseudo-RPG method of progression.

All of this is simply to keep up with the Joneses, let alone bringing players something that's new or better than what they've experienced before. It is worth noting that not every blockbuster game looks like this, and indeed, one of the trends in gaming over the last decade is a general narrowing of what both audiences and publishers consider "AAA" to mean. Aside from a marketing term that PC Gamer isn't a fan of. Nonetheless, the open-world blockbuster certainly represents the zeitgeist, and those games that don't ascribe to it will nonetheless borrow many of the ideas and mechanics that you commonly see in open world games.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Even if we reduce these games to the thing they're best known for—pushing the graphical envelope—the industry is increasingly experiencing diminishing returns. The visual difference between games made in 1992 and 2002 is vast. The difference between games made in 2012 and 2022? It's still visible, but nowhere near as dramatic. Making any further graphical gains requires a disproportionate amount of effort, as demonstrated by the hardware demand of ray tracing compared to the visual improvements the tech actually provides. That's a bit of a problem when you've spent the last 30 years luring in players with those exciting graphical leaps.

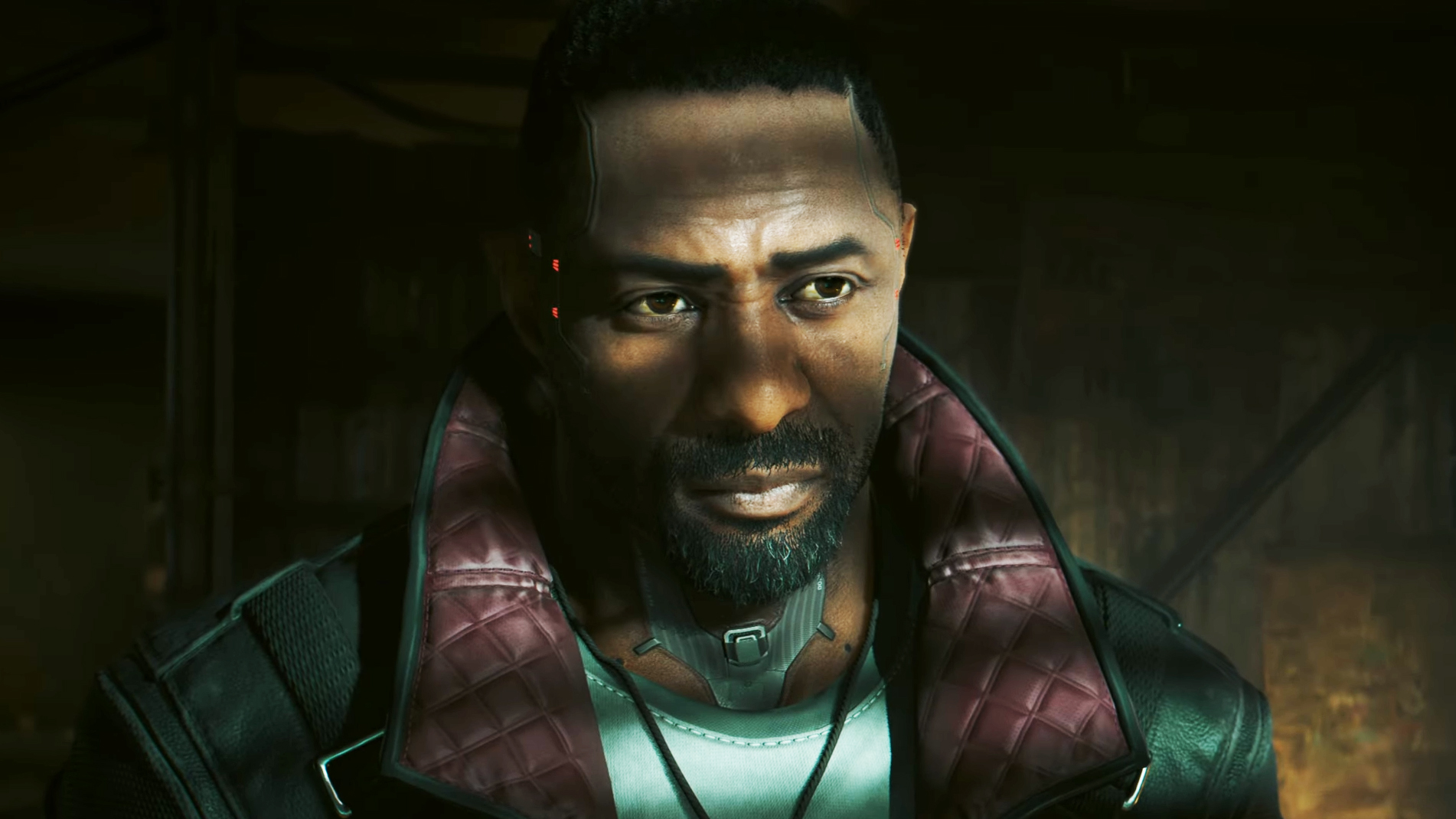

In short, modern gaming audiences are hard to impress, so impressing them requires substantially more effort. This means bigger-budgets, larger teams, and considerably more time. The standard development cycle for a modern blockbuster is generally accepted to be four years (By comparison, Quake, the most advanced game of its day, took two years to develop, which was considered anomalous at the time). But many of these projects are running beyond that four-year cycle. Rockstar went five years between releasing GTA 5 and Red Dead Redemption 2. CD Projekt had a five-year gap between The Witcher 3 and Cyberpunk. It took 343 six years to release Halo Infinite after Halo 5. Rocksteady Studios hasn't released a game since 2015.

Now bear in mind that game developers are creative people, and generally speaking, creative people A) want other people to see their work and B) value their individualism, and don't enjoy feeling like a cog in a giant machine. Hence, for any game designer, working on a small part of a massive game in a team of hundreds, for what is increasingly a minimum of four years, can't be easy. And that's the best-case scenario. You might work on a game that gets cancelled, or several games that get cancelled. And depending on what contracts you signed, you may not be able to talk about any of those projects—which could represent a decade of your life's work—on pain of being sued into oblivion.

Talk to any developer who has worked at a major studio, and they'll tell you that none of this is unusual—it's how the industry operates. We haven't even got to the more unpleasant problems associated with game development. The infamous stories of crunch, the death-marches, the constant reports about toxic management, or sexual abuse and harassment. Oh, and there's the fact that game developers are significantly underpaid compared to equivalent roles in other industries.

Across the board, developers are becoming fed up with how the big-budget game industry treats them—whether that's a consequence of mismanagement, or simply the existing systems at play. Some are establishing unions, while others are simply departing for greener pastures, forming their own studios or transitioning to other industries. As a result, the big studios are currently struggling to recruit the talent they need, likely the reason we've recently seen so many games announced extremely early in their development.

The delaying effect of the pandemic will hopefully fade away through 2023. But the hard questions the industry has yet to answer will remain. How much longer can big-budget games continue to rely on technical fortitude? How does the industry prevent development cycles from ballooning further, while also reforming itself to be a safer, fairer, and more inclusive workspace? How much longer will players be wowed by massive open worlds, and what, ultimately, does the next wave of blockbusters look like?

Rick has been fascinated by PC gaming since he was seven years old, when he used to sneak into his dad's home office for covert sessions of Doom. He grew up on a diet of similarly unsuitable games, with favourites including Quake, Thief, Half-Life and Deus Ex. Between 2013 and 2022, Rick was games editor of Custom PC magazine and associated website bit-tech.net. But he's always kept one foot in freelance games journalism, writing for publications like Edge, Eurogamer, the Guardian and, naturally, PC Gamer. While he'll play anything that can be controlled with a keyboard and mouse, he has a particular passion for first-person shooters and immersive sims.