2015 Personal Pick — Prison Architect

Along with our group-selected 2015 Game of the Year Awards, each member of the PC Gamer staff has independently chosen one game to commend as one of the best.

Early on in my first game of Prison Architect, I found I had to readjust my thinking. I'd been playing the good warden, being as attentive as possible to my growing population of inmates, constantly checking their list of needs to see how I could improve things for them. Were they missing their families? I built payphones, a mailroom, and scheduled time for visitations. Were they looking for ways to improve themselves? I built classrooms, a library, and acquired grant money for alcohol and drug rehab, workshop training, and other life-enhancing programs. I added a second kitchen and cafeteria after noticing some prisoners weren't getting enough time to eat, and I put bookshelves and TV in every cell to ensure they weren't bored. For a while, I treated Prison Architect like any other building and management sim. If I kept everyone happy, surely nothing could really go wrong.

Then five prisoners escaped. They'd been digging a network of tunnels at night with tools they'd smuggled from the workshop, and they dug their way to freedom right under my wall. That's when it finally sunk in: Prison Architect isn't really like other sims. Sure, there's the same management tasks like planning, construction, power and water distribution, budgeting and schedules—but no matter how hard you try to satisfy the needs of your civilian population, it won't change the fact that they're prisoners. Work hard at creating a humane facility and there may be no outright complaints, no violence, and no major disasters, but there will never, ever be real happiness. No one wants to be there, and even the best of wardens can't change that.

Prison Architect works well on both a large and small scale. The planning and construction of buildings is enjoyable and challenging, and I'd even find myself mentally planning projects when I wasn't actually playing. It can also require a laser-like focus on specific issues and even on individual inmates. After a virus swept through my prison, I had to check each individual prisoner for illness and lock the sick ones in their cells, one by one, to avoid spreading the disease further. Another time, an informant told me one of my inmates had been targeted for a hit because he was a former prison guard. I put the target in solitary while I set about planning a new protective custody wing to keep at-risk prisoners safe from other inmates. I eventually realized I hadn’t paused the game while planning my new annex, and that he’d been released back into gen-pop. I found him just in time to see him being stabbed to death in the cafeteria. Oopsie.

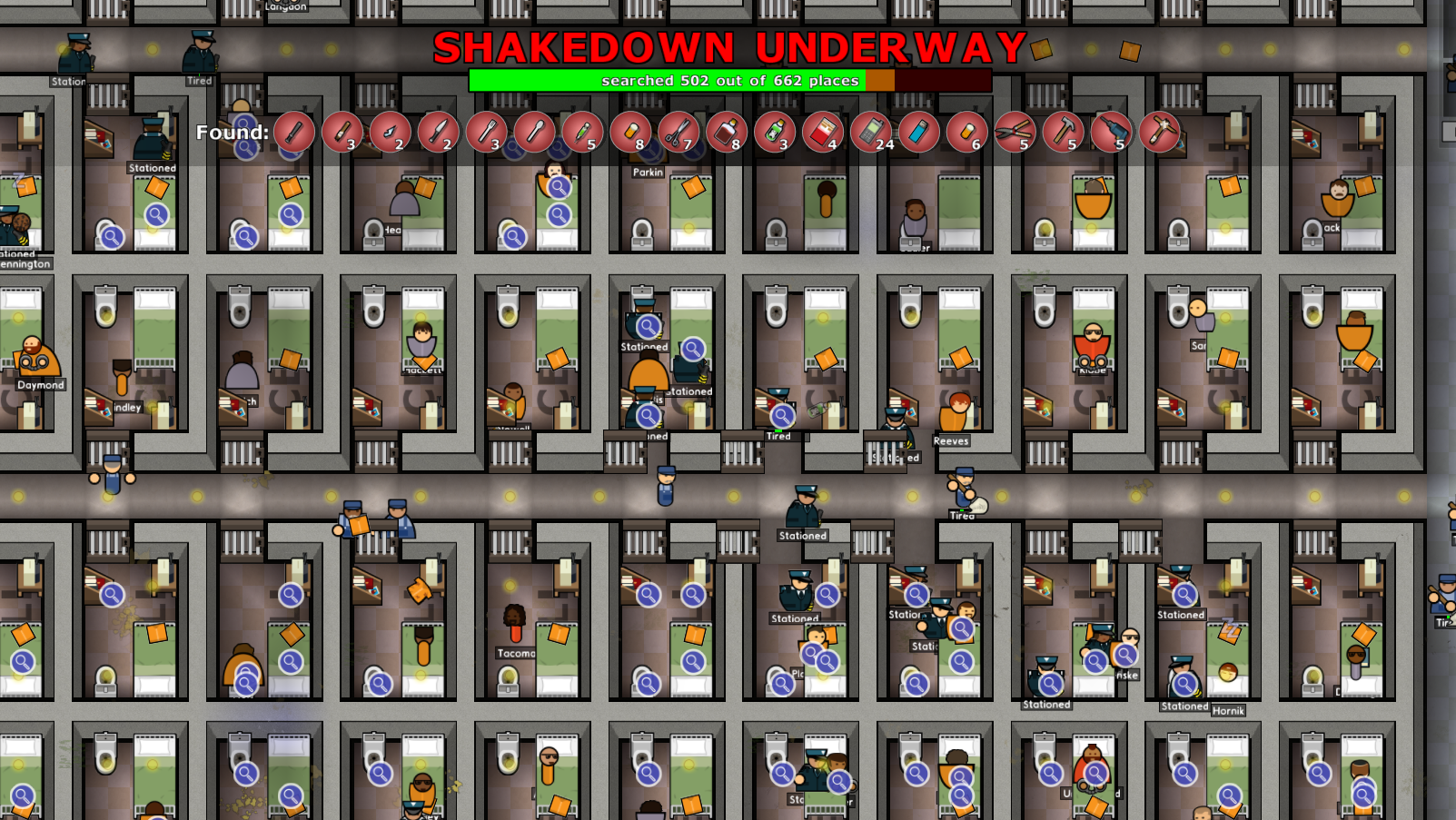

Trying to keep your prison free of drugs and weapons is a huge challenge until you learn a few tricks, and every time you turn around you'll find cellphones, drugs, and weapons arriving concealed in deliveries, smuggled in from other buildings, even thrown onto the grounds over your outer wall by visitors. Even when things are running smoothly it's hard not to feel paranoid and unsafe, leading to metal detectors at every door, tapped payphones and security cameras, frequent shakedowns and lockdowns of cellblocks, as well as an army of informants who provide good information but may wind up dead if anyone catches wind. It's an interesting feeling, staring at what is essentially a city similar to the ones in other simulation games, yet knowing every tiny little cartoon man on the screen hates you, is plotting against you, and wants nothing more than to leave your carefully constructed paradise far behind.

As grim as it all sounds, it's still a joy to play, a deeply engrossing exercise in planning and management, and there are plenty of ways to have additional fun, such as when I tried to escape from a modded-in Star Wars prison, and the time I built a prison to cater to a single inmate.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Chris started playing PC games in the 1980s, started writing about them in the early 2000s, and (finally) started getting paid to write about them in the late 2000s. Following a few years as a regular freelancer, PC Gamer hired him in 2014, probably so he'd stop emailing them asking for more work. Chris has a love-hate relationship with survival games and an unhealthy fascination with the inner lives of NPCs. He's also a fan of offbeat simulation games, mods, and ignoring storylines in RPGs so he can make up his own.