GameTrekking interview: "I released a new notgame from Cambodia today"

Back in September 2010, TIGSource 's founder Jordan Magnuson set off on an audacious project - travelling around South-East Asia, making indie games about his experiences along the way.

He called the project GameTrekking , and funded it with more than £3,000 of donations solicited from the web. Contributors to the fund get email updates from Magnuson and beta access to games in development, and those who contribute more get postcards from the road, links on his website, and even a credit in the games themselves, which are free, open-source and cross-platform.

PC Gamer spoke to Magnuson about doodling, genocide, and his experiences on the road.

PC Gamer: You've described some of your work associated with this project as "notgames". What are notgames?

Jordan Magnuson: I call some of my creations notgames to emphasize the fact that they are neither games, nor tools.

Because of the way the interactive medium and the gaming industry have developed, there's this huge expectation that when you sit down at your computer to have some kind of immersive interactive experience, what you're going to be doing is playing a game, because true to their name most computer games are, in fact, games. Now the discussion of what precisely makes a game a game gets into a lot of semantic technicalities, but we can all recognize certain elements that tend to be common to most games, whether we're talking about American football or Carrom , Mancala or Pac-Man: things like goals, rules, balance, challenge, interaction, and some elusive notion of "fun".

The rules that govern games can be interesting and fun, but they can also be quite limiting when it comes to expressing an idea or creating an engaging interactive experience; it's easy to frustrate people at the expense of engaging them, and people who lack the specific skill set that a particular game requires are essentially unable to enter into the conversation at all.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

I think there will absolutely always be a place for the kind of skill development and human interaction that games naturally foster. But I think with computers we have all kinds of potential to create interesting interactive experiences that are not limited by the rules that govern games - experiences that are less about skill, competition, and racking up points, and more about exploring ideas, emotions, emergent narratives, and all the things that make us human beyond gameplay. We've really done very, very little to explore that potential.

Part of the problem, I think, is that we have no name for interactive creations that are neither games nor tools, and language powerfully affects our perception of potential.

So that's what I'm working on these days: my whole gametrekking project is an attempt to expand the boundaries of interactive expression ever so slightly. I call many of my creations "notgames" in an effort to draw some awareness to fact that there's this whole unexplored world of potential out there in the gap, even if we haven't yet named that potential.

PC Gamer: Your website, NecessaryGames.com , describes itself as a repository of games that have meaning and significance, and several of the games you've made deal with very dark themes. What have you got against fun?

Jordan Magnuson: Haha. I really don't have anything against fun. But I do think there is a dearth of games that can really be considered meaningful or significant, partly because, as I was just saying, the rules and restrictions of gameplay don't really lend themselves to exploring those things. I created NecessaryGames.com to try and highlight some games that might be considered meaningful, and open up a discussion there.

Just to clarify, I don't really like the fact that my own creations are hosted on the site, as it may give people the impression that I am presenting my own work as being the height of "meaning" and "significance" in games, which is not my intention. I started dabbling in experimental game creation after the site had already been going for some time, and I posted my work there just because it was the most natural place for me to do so. Whether any of it is worth anything is entirely up to others to decide.

Yes a lot of my games and notgames deal with dark themes. Some of them deal with death, killing, genocide. I don't think these are the only themes that games should be addressing, by any means, but I do think they are important themes that need to be addressed precisely because of the thoughtless and insensitive ways that games have addressed them in the past. When you think about it, nearly all of the games we make are already about death, already about killing, already about genocide.

But the expression of these things in our games has become so abstracted and dehumanized that we no longer recognize them for what they are. Death, as perceived through most of our computer games, loses almost all of the meaning it has had in the context of human lives and relationships throughout history. Thus, when it comes to the most significant themes in human experience, computer games have the tendency to strip meaning and significance out of those themes, strip empathy and understanding away from the people who play them.

I'm not saying I'm against RTS games, or chess, or even first person shooters. I'm just saying that for every game we have that makes life and death abstract to some extreme degree, I think we also need a game (or notgame) that solidifies them, humanizes them, reminds us of what we used to know about them.

PC Gamer: You're also one of the few people in the world making games about travel. What is it about travel that you feel lends itself to indie games?

Jordan Magnuson: The reason I was drawn to make games (and notgames) about travel is that nobody else was doing it. I love travel. I love learning about new places. I love coming into contact with different worldviews. I love watching the interactions of cultures around the globe. But where are the games about these things? Where are the notgames? This is just one example of one of the many, many spheres of human experience that remains virtually untouched by the games industry. Because the industry isn't concerned with exploring the myriad facets of the human experience: it's concerned with finding new ways to implement addictive gameplay mechanics, and with building profitable franchises.

That's not going to change. So we need people outside the industry who are willing to experiment and take risks, who are willing to try and make games and notgames about everything that the industry is ignoring. With the gametrekking project I decided to put my money where my mouth was, and try to be one of those people.

I'm afraid I'm making myself sound very heroic, but rest assured that I am no such thing: I just see a huge potential for the growth of a medium that very much excites me, and I want to be a part of that in any small way that I can. The things I make are not epic, or brilliant, or revolutionary: they are just sketches, doodles, prototypes, and experiments. But I personally think that what we need right now are a lot of experiments, a lot of sketches, and a lot of doodles, so I'm happy to doodle away, even when countless others can do so better than I can.

PC Gamer: Has the pressure of having donors to satisfy changed how you approach gamemaking?

Jordan Magnuson: Somewhat. Having donors has made me more keenly aware of the quantitative side of things. There's this feeling that I need to produce a certain quantity of games in order to live up to my side of the donor-recipient bargain. Which is both good and bad. I'm a perfectionist, so my natural tendency is is to view any kind of quantitative measuring stick as a bad thing: quality beats quantity in my book every time.

But I also have to remember that what I'm doing here -- as I just said -- is sketching and doodling. Sketching and doodling are activities which profit greatly from an emphasis on quantity, because the point of a sketch is never to make something of great quality, but rather to make something that might serve as a springboard to something better later on.

From that standpoint, the more sketches one can churn out, the better. Which is part of the reason I created the gametrekking Kickstarter project: to force some kind of accountability there, to force myself away from my perfectionist tendencies.

Still, my creative process tends to function in a somewhat unpredictable, haphazard way, and my perfectionism has a nasty habit of hanging on. Add the strain and time requirements of independent travel to the mix, and you have a recipe whereby it is often difficult for me to meet the quantitative goals I set for myself, which sometimes leads to stress, which sometimes diminishes my creativity. So like I said, good and bad.

PC Gamer: You've made it through five countries but with games only listed on your site for one of those, not including Korea. Is finding the time to make games proving more difficult than you imagined?

Jordan Magnuson: Haha. Like I was just saying: yes. The kind of fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants independent travel that I'm engaged in just takes a lot of time, especially once I add in the research I'm attempting to get done for each country I travel through (I like to read histories, as well as local fiction and poetry, watch local films, etc), I find myself fairly swamped most of the time. On top of that, game development is fairly time-intensive even when it comes to very small projects, and I'm tending to find that it's not an activity I can complete very successfully in short spurts (like I can do with reading, or writing). I do much better if I can get periods of several hours to focus on creating something.

So right now I'm attempting to balance days of constant travel with days of development-focused stasis, but doing so has been difficult: "down time" is generally as expensive as "up time" (if not more so), and finding good environments for productive work (with power outlets, dependable internet connections, relatively low noise, etc.) is not always easy in places like Vietnam or Cambodia.

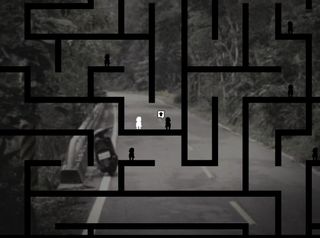

I actually just released a new notgame from Cambodia today (play it here ), and I've got some things in the hopper, but I'm also coming to terms with the fact that I'm probably going to continue to be behind in my quantitative development goals for as long as I'm on the road. I will probably get to the end of my trip and have a significant backlog of ideas to work on.

PC Gamer: What software tools do you use to put games together on the road, and how do you use them?

Jordan Magnuson: Basically, I'm coding all my games in ActionScript 3 right now, which allows them to run in Adobe's Flash Player, which means just about anyone can play them in a web browser without having to install anything. I use the excellent (and free) FlashPunk library to give me a base for game development on top of AS3, and I do the actual coding in FlashDevelop, which is a free code editor for ActionScript.

PC Gamer: What are your future plans for the project? When you're done in South-east Asia, will you keep going?

Jordan Magnuson: My funds will be running rather low by the time I get out of Southeast Asia, but there should still be some left, so we'll see. One option I've looked into is taking the train from Hanoi to Beijing, then the Trans-Siberian across Russia.

PC Gamer: Finally, do you have any advice for anyone else contemplating a similar game-making expedition? Anything you wish that you'd known before you started?

Jordan Magnuson: I think it's unwise to count on getting much done on the road. When setting up this project I was probably overly optimistic there, which is why I'll end up with a backlog of work to do once this trip is over. In the future, if I were to do something like this again, I would probably try to fund shorter trips (maybe a few weeks) to individual destinations.

I'd do most of my research beforehand, spend the trip focused on the actual traveling, journaling and gathering of materials (photos, interviews, music, sound clips, etc.), then come back home and put the games together in a more relaxed, focused setting. Of course, there would be steeper funding challenges to an approach like that, and it would lack some of the unique challenges and opportunities afforded by extended travel.

Despite the difficulties, my gametrekking journey has been an amazing trip so far, and I'm very grateful to all the people who have made it possible. At this point I really just want to fulfill my side of the bargain by giving back as much as I can.

Follow Jordan's journey on his travel log , and play the games he's made so far on GameTrekking.com .