1998 text adventure classic Anchorhead is an uncanny addition to 2018's lineup

An illustrated and expanded version of the Lovecraftian horror game released on Steam and Itch.

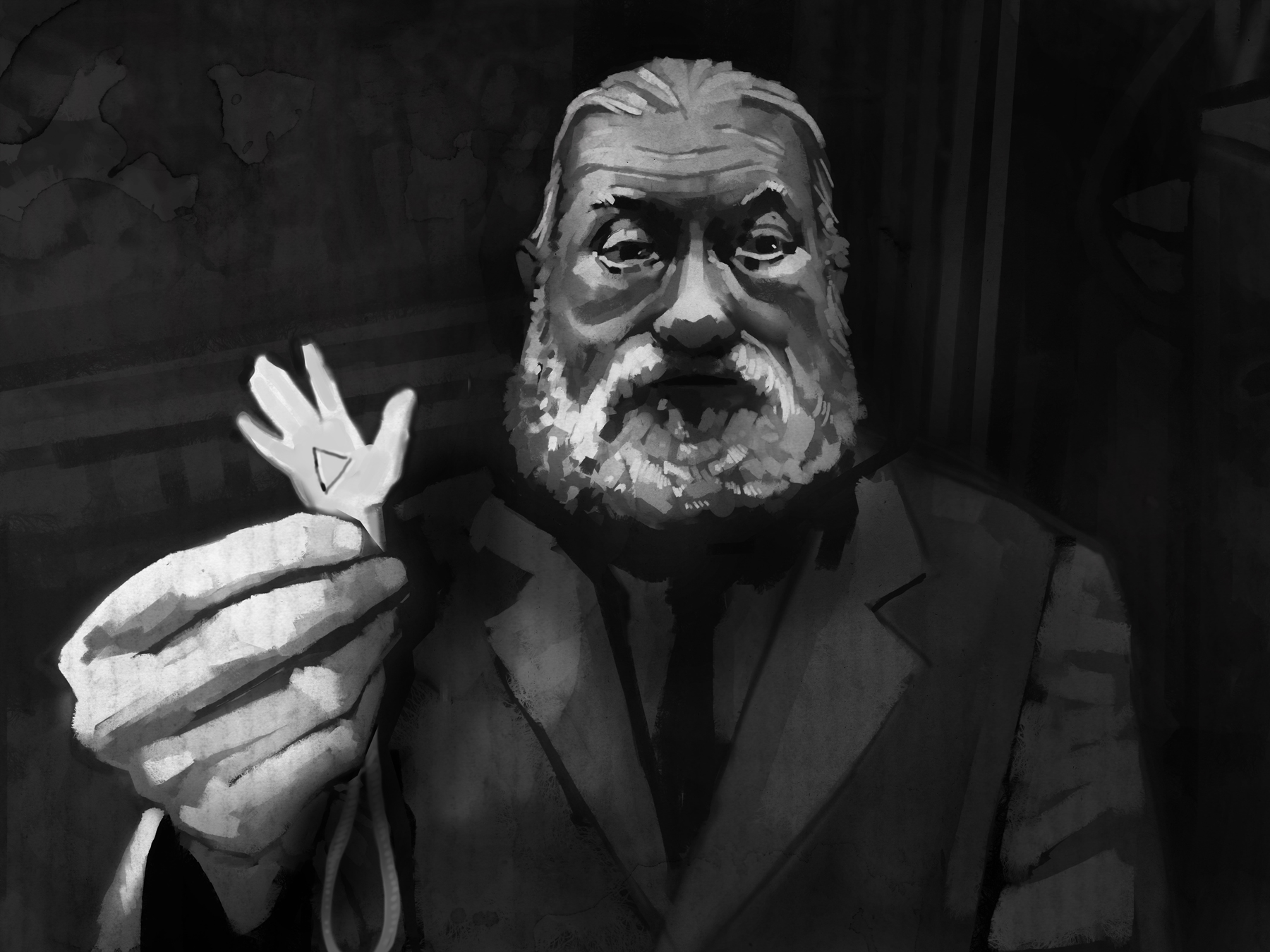

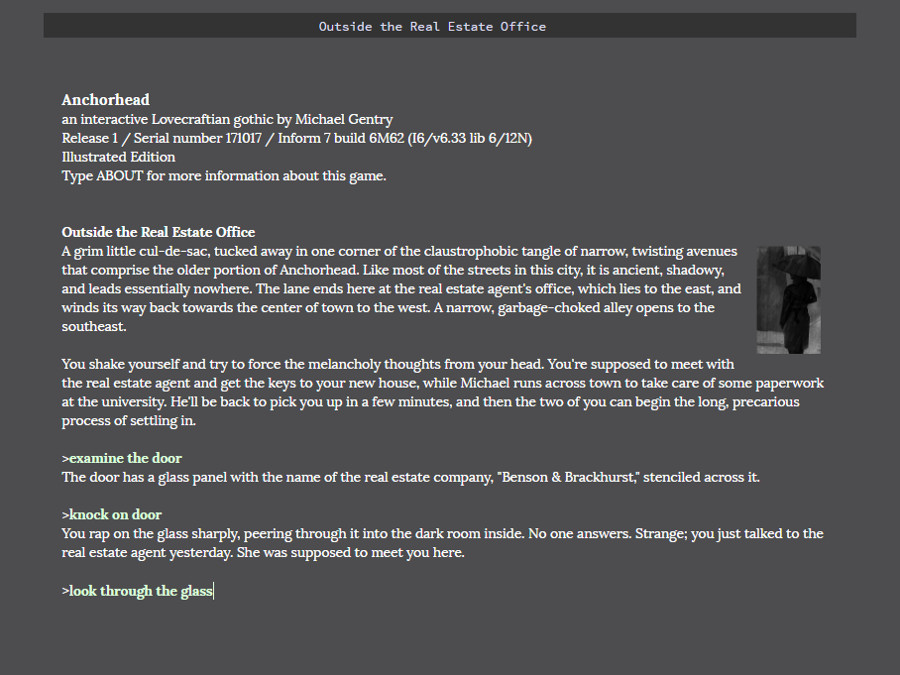

Anchorhead just arrived on Steam and Itch, 20 years after its original 1998 release. Michael Gentry's classic work of interactive fiction has received a visual update and additional content for its re-release, but it's not trying to hide its origins: it's still a text adventure in the Infocom mold, an interlocking story built around puzzle-solving, inventory management, and exploring a large map of interconnected locations. It bears reexamining, both because it's a pivotal game in the history of interactive fiction, and because of the place it might occupy in games culture in 2018.

A Lovecraftian gothic story, Anchorhead puts the player in the shoes of a woman whose husband recently inherited a mansion left behind by distant relatives—and, of course, he also inherited their family curse. Anchorhead revels in Lovecraftiana, and at times it feels like a tour of the highlights: there's a monstrous child like in The Dunwich Horror; there's shades of the hereditary possession of The Thing On the Doorstep; there's the cult-gripped New England town straight out of The Shadow Over Innsmouth complete with a homeless man who'll exchange exposition for whiskey.

Like Lovecraft, it's obsessed with decay, antiquarian histories, and above all with writing. There are reams of newspaper clippings, cryptic journals, and archaic tomes to uncover—paper has been shoved into almost every nook and cranny.

A confluence of setting, theme, and genre lifts up Anchorhead. Lovecraftian protagonists are everyday people, often scholars or investigators, thrust into horrific circumstances. Anchorhead's focus on all of the ancillary reading, the mundanity of its puzzles, all of that fits. And while many parser-based games of this era avoid NPCs because of how hard it is to make them lifelike, Anchorhead has a fairly expansive cast.

It's possible to render the game unwinnable on day three because you didn’t pick up a towel on day two. It's that kind of game

Part of what makes that cast work is a willingness to lean into adventure-gameness, sometimes to the point of straining realism. But it also works because the small town of standoffish, sullen people is a relevant trope here. Michael, the protagonist's husband who is suddenly not himself, appears stiff and mechanistic, but rather than undermining the story, this enhances it.

Of course, being tangled in Lovecraft's obsessions can be uncomfortable, too. There's no real way to wipe the rancid racism off Lovecraft's writing, and in some of its passages Anchorhead seems too close to it for comfort. At the same time, it features an explicitly female player character (a rarity in interactive fiction at the time, and nonexistent in Lovecraft) and sometimes seems to recast the horror at the heart of its story as a sort of patriarchal specter—definitely not something found in Lovecraft.

Not everything works. Where solving the mystery is also a sort of puzzle, it sometimes leans on over-exposition and redundancy of information in a way that is decidedly un-Lovecraftian. It struggles to give enough clues in enough different places for someone playing the game blind—something that makes the game feel overexposed when you play it with a walkthrough, which is the experience a lot of players get. Mercifully, it makes no attempt at emulating Lovecraft's prose.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

For all its narrative depth, Anchorhead is still a text adventure through and through. Its world revolves around hidden crawlspaces and the time-worn practice of picking up everything that isn't nailed down. It's possible to render the game unwinnable on day three because you didn't pick up a towel on day two. It's that kind of game, large and unforgiving, and playing without a walkthrough is definitely frustrating for all but devotees of the genre.

There's a sharp break in the history of interactive fiction right after Anchorhead: 1998 saw the release of Photopia, a mostly linear, mostly puzzle-less interactive story that reads now as a clear antecedent to the personal and literary work that would come out of Twine many years later. Parser games would become shorter, more experimental. When they are driven by puzzles, those puzzles are friendly and jokey (Lost Pig, Taco Fiction), and gently try to lead you towards finishing the game rather than leaving room for failure.

Anchorhead, then, sits in an awkward place. Though widely praised, it's still an example of a design language that was soon abandoned in favor of something more accessible. The re-release also fits in awkwardly with the gaming world of 2018.

It's the last great example of the sort of puzzle-and-exploration-driven design that Infocom championed.

For a long time, parser games struggled with their inaccessibility and niche quality—getting mainstream gaming websites to even talk about them (especially in terms other than "Text adventures? Wow, they're not dead!") was an uphill struggle. Now gaming has opened up to the arcane, inaccessible, and unyielding in an unexpected way.

Minecraft became the biggest hit in a generation while being pretty much unplayable without consulting a wiki. Dark Souls incorporated outside assistance and "walkthroughs" into itself as a mechanic outright. Shenzhen I/O was a success perhaps because it asked you to print a long manual to be consulted from a three-ring binder, not in spite of it. Our ideas of frictionless, self-explanatory, soft play—dogmatic and dominant throughout the 2000s, and frankly distressing to fans of niche genres like roguelikes and parser interactive fiction—have dissolved in the face of the clear success of games that don't play by those rules.

At the same time, interactive fiction has definitely passed Anchorhead by, and there are few descendants of this kind of design around to compare it to. It's the last great example of the sort of puzzle-and-exploration-driven design that Infocom championed. A type of design that seems out of place in our game-saturated world, that was meant for the obsessive enjoyment of players who could pore over a single game for months at a time, trying to find its secrets.

Befitting its Lovecraftian themes of familial collapse and doomed lineages, Anchorhead has no real grandchildren to compare itself to. So much of its design—the puzzles built around "medium-sized dry goods," the possibility of silent failure, the twisty little passages—are things that quickly became either quaint or actively reviled. It's probably the last game that both included a maze and was widely praised by the interactive fiction community.

Games like this were the product of a hobbyist obsession with recreating Infocom's classic 80s games, with a seriousness and understanding of that design that was only possible to hobbyists. But the community they spawned, and the tools they built, were eventually turned toward experimentation—toward trying to discover new forms instead of refining an old one to a sharp point. Anchorhead is that sharp point, so complete in its use of these ideas that trying to follow it up with more of the same must have seemed pointless.

This leaves the re-release of Anchorhead in a strange place. If this were a brand-new game, it's hard to imagine a reaction from the interactive fiction community that wasn't a bit bemused someone put mazes into a game in 2018. At the same time, maybe now is the best time in a long time to present something like this to the general gaming public—maybe tastes have shifted toward it. Anchorhead will never be a universal hit, but I'm curious to see what people who haven't been steeped in interactive fiction make of it.

And if you haven't played a parser game before, maybe give Anchorhead a try, especially if you enjoy this brand of horror. If you do: save often, and on different files, and don't be afraid to ask for help or get a walkthrough. In 2018, I think we can admit that's just part of the play in games like this one.