12 stories from crazy '90s PC gaming ads

A CD speedup tool investigated by the FTC, the story behind Fallout's S.P.E.C.I.A.L. RPG rules, and more.

With all the talk of false advertising and dodgy marketing lately, I've been thinking a lot about the '90s. Specifically, the bombastic and oftentimes outrageous promises games would sell themselves on back then. Who could forget John Romero's assurances that he'd make us his bitch, or Tomb Raider's focus on Lara Croft's chest? You could get away with a whole lot more cock-and-bull 20 years ago, along with the kind of straight-up absurdity that simply wouldn't fly in today's markets. Feeling nostalgic, I plunged into the wild world of pre-2000s PC gaming magazines and picked out some of the most bizarre advertisements the '90s had to offer. Prepare your eyeballs for a journey into the Xtreme.

Note: Scans sourced from the Internet Archive and Computer Gaming World Museum

When the first Fallout released, it bore the subtitle 'A Post Nuclear Role Playing Game,' but that's not what it was always going to be called. Originally, Fallout was intended to license Steve Jackson's Games' GURPS, an alternative role-playing system to Dungeons & Dragons. After some initial skepticism, Jackson agreed to the project, and in light of the game's iconic vaults, it was dubbed Vault 13: A GURPS Post-Nuclear Adventure.

Over the course of development, this name changed to Fallout: A GURPS Postnuclear Adventure, as seen in this ad. It wasn't until early 1997, when creative differences between Jackson and Interplay led to Jackson leaving the project, that the GURPS name was dropped, and its systems replaced with the S.P.E.C.I.A.L. ruleset we know today.

CD Speedster: PC Zone, October 1997

Dumbbell-shaped goggles and a face full of broken glass; finally, an ad I can really relate to. I've always wanted my discs to spin so fast they shatter into a million pieces! Thanks Syncronys!

In truth, though, the weirdest part of this ad isn't the guy so extreme his hair has motion blur, it's the product he's trying to sell. CD Speedster was one of those PC tune-up tools you still see lurking in banner ads and Google promoted search results—Is your PC running slow? Download our one-click Computer Cleaner; no malware, we swear! Claiming to speed up CD-ROM access through software alone, CD Speedster simply cached CD data on the hard drive using its misleadingly titled 'Dynamic RAM' technology—really just a page file. Can you imagine paying $25 for something that basically installed a CD to your hard drive? Bizarre.

Even more insidious, Syncronys also produced a program called SoftRAM which claimed to double available memory in Windows without the need for slotting in more RAM. Pretty wild, huh? The FTC thought so, too, charging Syncronys with false advertising after an investigation found the software not only did nothing to increase RAM, it actually caused a system to perform worse thanks to an errant debug flag in the final code. This sham, along with other dubious 'tools' like CD Speedster, led to Syncronys filing for bankruptcy in July 1998.

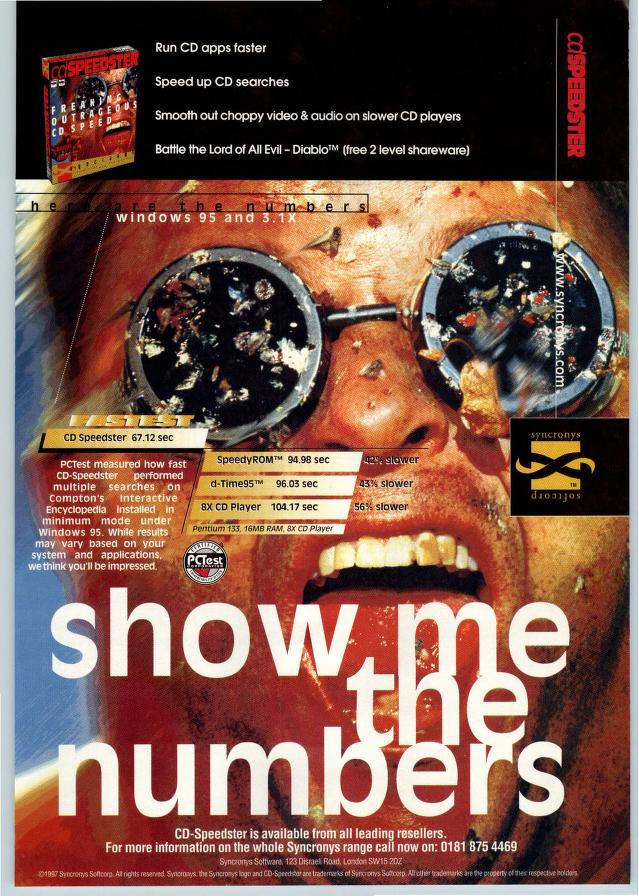

Zephyr Computer Corporation: Computer Gaming World, January 1995

Forget the state-of-the-art 90MHz Pentium processor or the massive 8 MB of RAM; the real star of this show is the upside-down Enterprise-looking thing sitting where the mouse should be. Dubbed the CyberMan—a strong contender for the goofiest product name of all time—the '3D' controller joined joystick and mouse in unholy matrimony in an attempt to solve a problem that didn't exist. DOOM controlled just fine with a mouse and keyboard, while Descent handled perfectly well with a joystick. There was little to be gained from combining the two.

Even from a novelty perspective, the CyberMan was a disaster. Its force feedback was likened to 'the Ultra-PleasureVibe 2000', while its three axes of movement were limited by the fact users had to contort their hands into claws just to move the mouse part around without accidentally depressing its buttons. Outside of the few games that supported it, it was supposed to function as a regular mouse, but even that didn't work properly: because it was fixed to its base, you could only move it so far in one direction before you had to lift it up and re-center it. Anyone who's tried to use the arm of a couch as a mousepad knows how well that works.

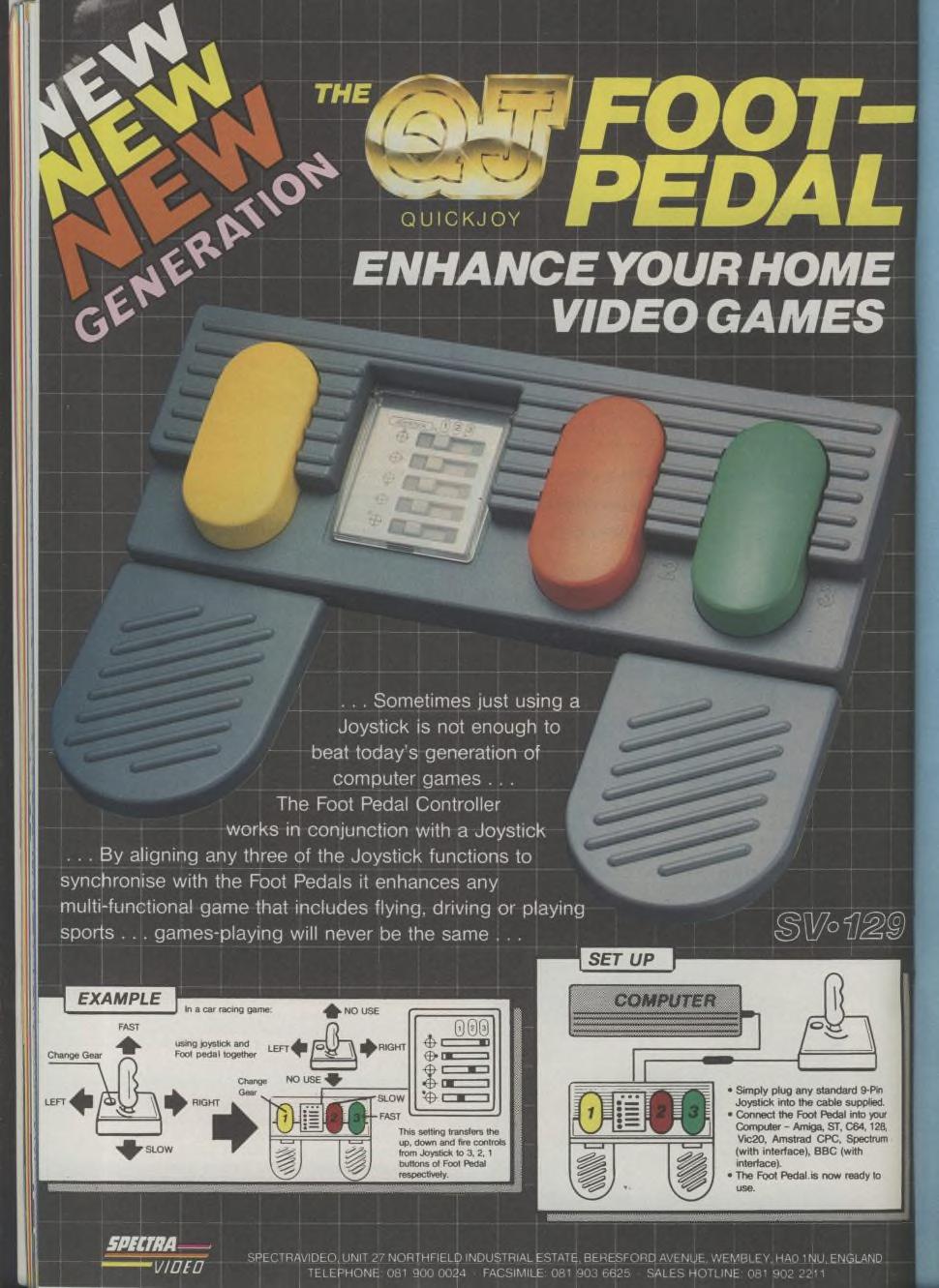

Foot pedal controller: Computer Gaming World, February 1992

Mice with a dozen remappable buttons are cool and all, but they haven't always been around. Back in '92, we hadn't even settled on a standard configuration for mice: Apple was still infatuated with its single-button design, while IBM and Microsoft flip-flopped between two- and three-button layouts. That didn't stop keen gamers from getting their macro on, though, even if the process was a little more analogue than it is these days.

The QuickJoy Foot Pedal controller was a marvel of ingenious absurdity. It sat between your joystick and your computer, allowing you to remap any of the joystick's four directions or its fire button to one of the three colored pedals. Instead of messing around with mouse drivers and proprietary software, you simply slid the controller's physical switches around to suit the game you wanted to play. For a 24-year-old piece of kit, it's pretty impressive, even if it does look like a PS1 controller beaten flat with a traffic light.

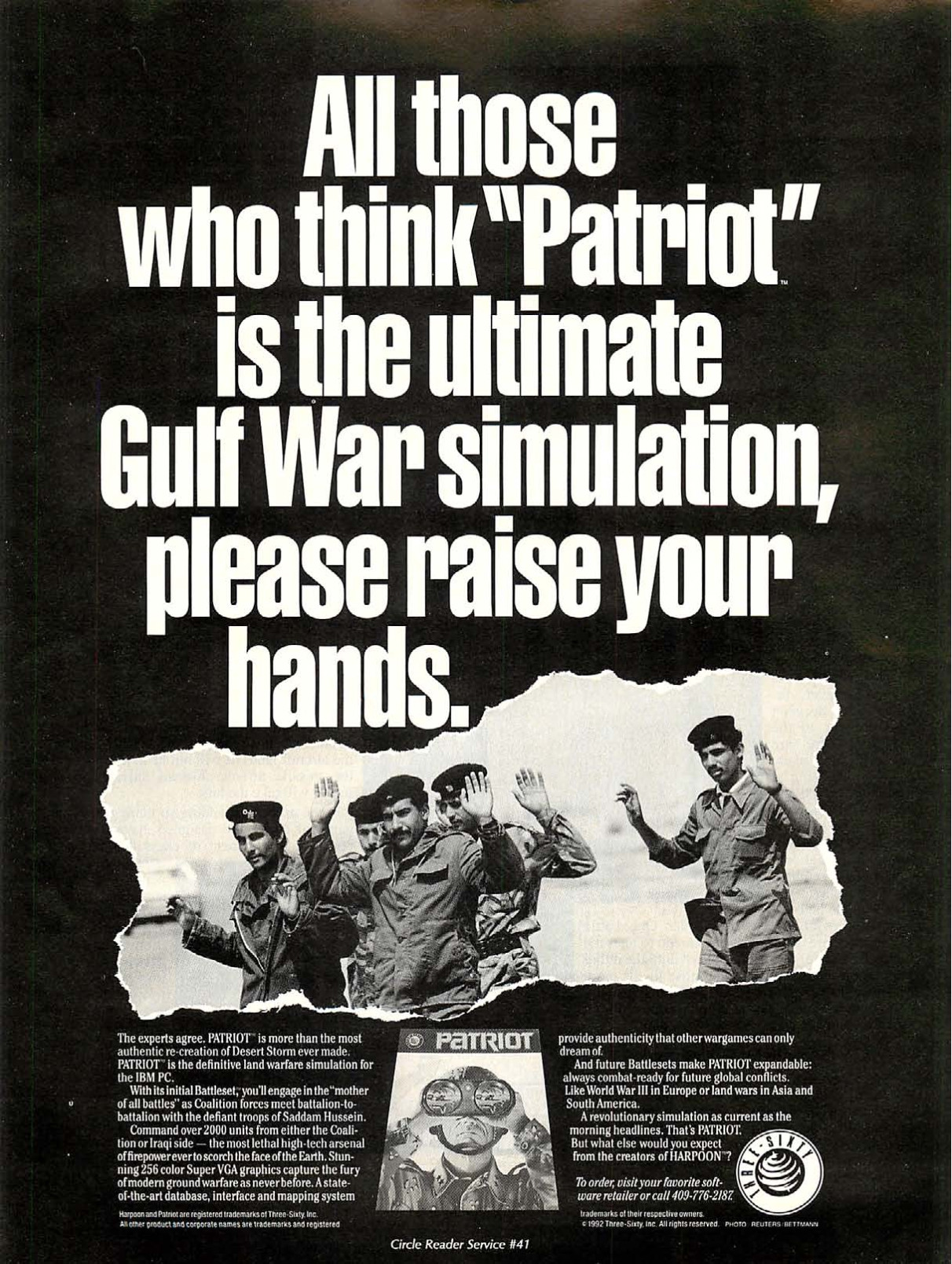

Patriot: Computer Gaming World, January 1993

Yeesh. Forget the Taliban-in-Medal-of-Honor controversy; this is a far more brazen attempt at exploiting war to sell video games. The photo depicted in the ad, taken by Russell Boyce in March 1991, shows Iraqi soldiers surrendering to the U.S.—a moment of triumph, perhaps, but one that came at no trivial cost to human life. To twist that moment into a crude joke for the sake of selling a game seems more than a little disrespectful to the horrors of war. For a game that purports to be 'more than the most authentic re-creation of Desert Storm ever made', it comes off more like a cheap attempt to cash in on the suffering still fresh in many people's minds.

Then again, apparently the game itself was pretty awful, so maybe the marketing was actually on point.

Werewolf vs Comanche 2.0: Computer Gaming World, December 1995

I've always thought those multi-pack game bundles on Steam are a good idea, bringing the per-player price down while at the same time growing a game's community. I'm far more likely to stick with a game if I've got friends playing it too. As it turns out, the multi-pack has a rich history in PC gaming. Back in 1995, the helicopter sim Werewolf vs Comanche 2.0 built itself around the idea of single-purchase multiplayer, bundling in two separate games—one, Werewolf, the other, Comanche 2.0—that supported network play against each other. It was a novel way of effectively doubling the player base, though given the two games were later repackaged and sold individually, I suspect it didn't do much for the sales numbers. It's no surprise the trend didn't really catch on, then.

A similar tactic that saw more widespread adoption was the spawn installation. This approach allowed a limited part of a game—typically just the multiplayer—to be installed on multiple PCs and played at the same time, DRM-free. Blizzard was one of the most notable studios to champion the feature, incorporating it into Warcraft, StarCraft, and Diablo. For a time, it was the staple of many a LAN party, the saving grace of cash-strapped PC players everywhere. Concerns over piracy eventually led to its decline, and these days it's all but forgotten, relegated to Nintendo's DS handhelds and their Download Play feature.

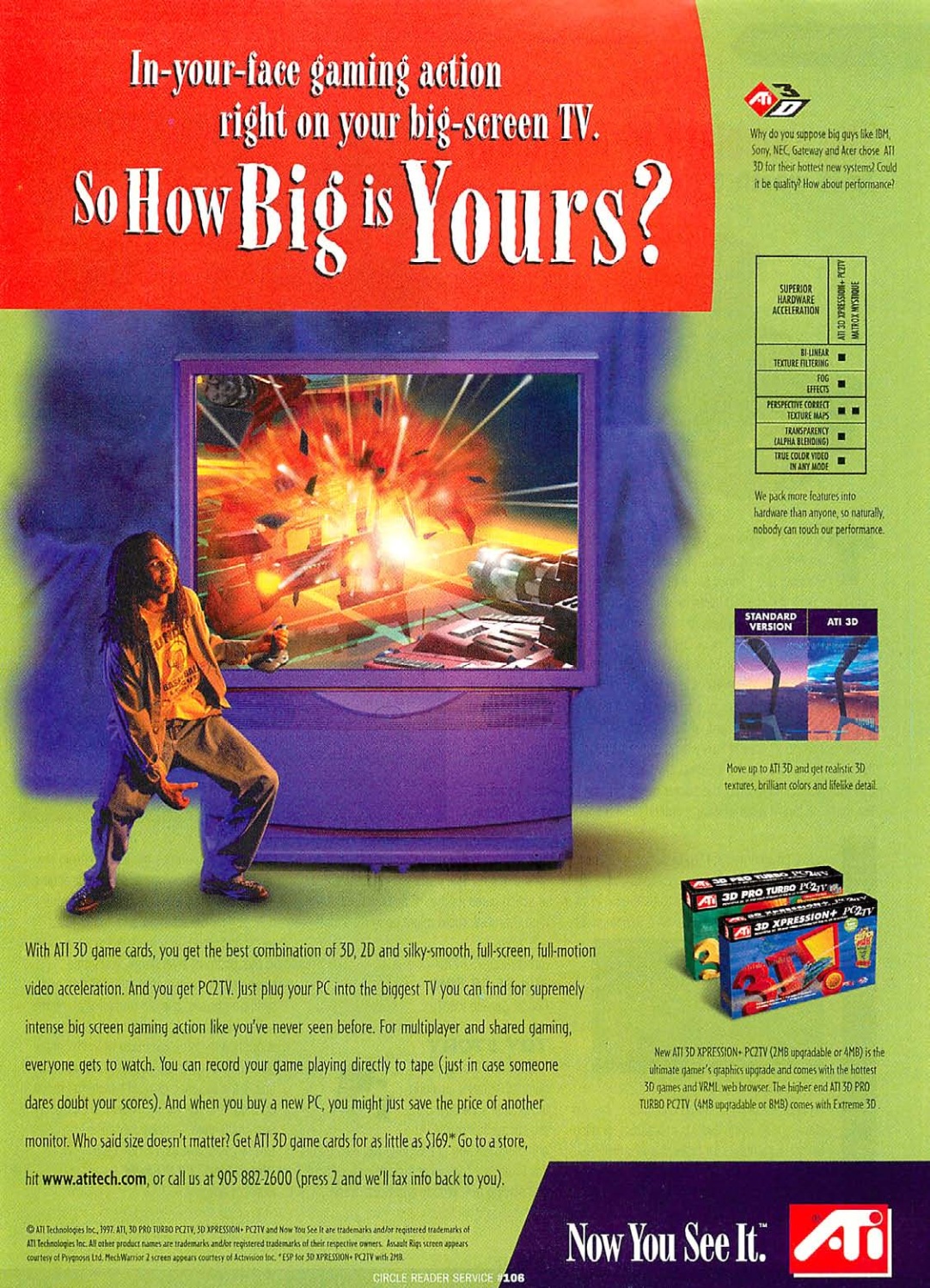

ATI PC2TV: Computer Gaming World, December 1995

Playing PC games on your TV is pretty easy these days. Whether you plug in an HDMI cable or stream over your Steam Link, you can get by just fine without a dedicated monitor. Back in the CRT days, the dream of playing X-COM on your couch was a wee bit harder to achieve, with few graphics cards supporting the composite and S-Video connections favored by most TVs. Good ol' ATI came to the rescue with its 3D XPRESSION+ PC2TV, a graphics accelerator built expressly with TV output in mind.

Playing games was only one of PC2TV's functions; more fascinating was its ability to connect to a VCR and record its video output to tape. Years before FRAPS would simplify video capture to a single button press, taping games was the only way to share proof of your 360 no-scope in Turok: Dinosaur Hunter. At a resolution of 333x480 and a maximum of 30FPS, it was about as good as you were going to get on VHS, and you could finally show off your mad Chip's Challenge strats. Don't forget to like and subscribe!

Sorority House: PC Gamer UK, January 1995

Oh, the '90s. A time of Playboy magazines concealed in school textbooks and excruciating minutes-long image downloads on patchy dial-up internet. Not that I had any experience with all that, of course. I just heard about it, from a friend of a friend. You wouldn't know him, he's moved away now and—oh, fine.

While I may have had some experience with the lurid '90s, I never encountered anything like this. Apparently, though, interactive adult entertainment was reasonably popular, enough for a full-blown (sorry) industry to rise up (really, I am). Mission Control was one such provider of digital titillation, operating via mail order and shipping CDs between the pages of fake encyclopedias—at least, that's how I want to believe it worked. How else did curious teens slip their packages in without their parents noticing (last one, I swear).

Spectre VR: PC Gamer UK, January 1995

This 'cyberiffic' 3D shooter is a monument to PC gaming's awkward adolescence, that confusing period in the mid-90s when floppy disks were on their way out and everyone was jumping on the CD bandwagon. Games like Spectre VR, System Shock, and X-COM: UFO Defense released on both formats, but their marketing always focused on the 'superior' CD version.

Screenshots, features, and review quotes rarely referenced the humble 3.5" floppy, and in a time before helpful side-by-side comparison videos, you often didn't know what you were getting until you'd handed over your hard-earned cash. Maybe the CD version simply added fully-voice dialogue and CG cutscenes; then again, maybe it included ten extra levels plus an entire multiplayer mode. Of course, that kind of thing would never happen these days, right?

Thrust World: PC Zone, April 1998

Remember when third-party gaming services were a thing? Back before matchmaking was baked into a game and you had to seek out and type in server IPs manually? No simple peer-to-peer connections, no global stat-tracking, and worst of all, subscription fees for the 'privilege' of playing online—I'm looking at you, AOL. It makes me really appreciate how much simpler online gaming is these days. We may still suffer the frustration of rocky MMO launches and the occasional console hand-me-down, but at least we're not forking out £18 a month for it.

Also, 'playing with yourself?' Really, guys? I'm so glad we've moved past tha— oh, wait.

Locus: Computer Gaming World, October 1995

Virtual reality is a familiar concept to most gamers in 2016, but back in the mid-90s, the term didn't always mean what it does today. Games like Locus and Spectre VR billed themselves as virtual reality experiences, but all that meant was that they looked like budget versions of Tron's light cycle scene or an X-Wing's targeting system. VR was tossed around like any other buzz term, the 'immersive' or 'visceral' of the 1990s. Inadequate technology might have been the Achilles heel of systems like Virtuality and the Virtual Boy, but the confusion surrounding what VR actually was certainly didn't help them any.

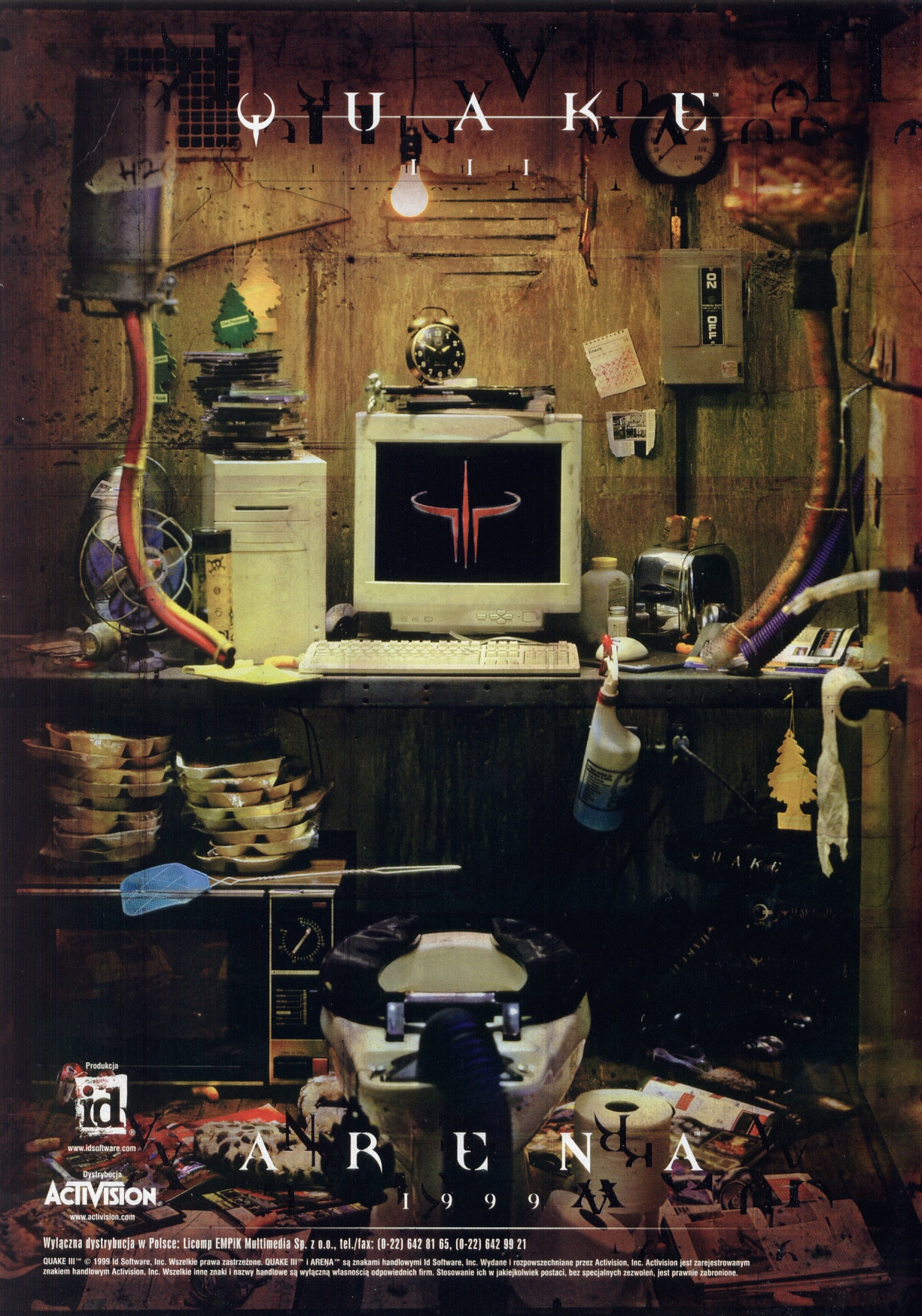

That rig there? That ain't no PC. It's a PowerMac, one of the 8000 series popular during the '90s. Heresy, you say? What is an Apple product doing in an ad for Quake, one of the most PC-ass first person shooters ever made? The truth is, id Software has been one of the strongest supporters of Mac gaming over the years. Quake III Arena, Doom 3, and RAGE were all first revealed at MacWorld events, with programming whiz John Carmack himself demoing the tech on stage. At MacWorld 1999, Carmack even said that he expected the Mac to be the 'perfect gaming platform,' which, for all the Apple fans out there, has sadly proven false.

Interestingly, Carmack hadn't always felt so optimistic about the Mac platform. In one of his .plan files from 1997, he wrote that he had 'zero respect for MacOS on a technical level.' He even flat-out stated that he 'wouldn't develop on it.' With Oculus Rift dismissing Apple until it releases 'a good computer,' it seems like Carmack's attitude has come full circle.