Our Verdict

The Division is a challenging co-op cover shooter and a gorgeous open world diminished by bloated and unnecessary RPG tropes.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? An open world co-op cover shooter with RPG dressings.

Reviewed on: Nvidia GTX 980 Ti, Intel Core i7-6700K, 16GB RAM

Price: $60 / £50

Release date: March 8, 2016

Publisher: Ubisoft

Developer: Ubisoft Massive

Multiplayer: 2-4 co-op

Link: Official website

I'm cornered by three strangers. They can see the loot I'm carrying on my back. I expect them to shoot any second—instead, all three start doing jumping jacks in unison. Welcome to The Division, where fitness comes first. It was a warm welcome, so I joined in and they helped me extract my loot from the PvP Dark Zone. We spent the next hour parading through central Manhattan, helping out strangers in need and hunting down rogue soldiers in a series of vigilante revenge quests.

But with or without impromptu friends, the vast majority of my time in The Division was spent sprinting between abstract world map icons, completing shallow side missions for incremental loot snacks (empty calories), and firing entire ammo reserves into soldiers whose superhuman health bars would be hearty enough to feed a family. Even an entire family of revenge-driven vigilante cardio enthusiasts. I miss them.

The Division is an open world RPG co-op cover (breath) shooter set in the ruins of Manhattan after a rough bout of Black Friday bioterrorism sent the city spiraling into a mini-apocalypse. Manhattan is quarantined, so the Division, a covert federal force, is sent into the city to restore some semblance of federal civility (by shooting everyone highlighted in red on sight).

I spent over 30 hours sprinting between icons in a beautifully rendered open world, which is typical of Ubisoft games. But The Division doesn’t lift the Assassin’s Creed template directly, as progression through the open world leans on traditional RPG mechanics. I leveled up my soldier, unlocked new abilities, and scoured the world for better guns and gear. I had fun with the campaign, but at the expense of 22 hours of filler, and I won’t go back.

Take cover

The Division is a collection of story missions, side missions, and random combat encounters strewn throughout the world. You can opt to tackle them alone, with three friends, or strangers via matchmaking. Safe houses function as small social hubs and the only places you'll run into other players (besides the Dark Zone, which we’ll get to); the rest of the open world is limited to you and your team.

Combat can be tense and challenging, especially with teammates. Press a key to take cover on corners or highlighted chest-high objects. From cover, you can blind fire, take aim, toss grenades, or use one of your class abilities, like throwing out an automated turret that suppresses nearby enemies or a med station that heals everyone in a visible radius. I rarely had time to dig in, as enemies flanked or sent explosives my direction with reckless abandon. Under that kind of pressure, I changed cover a lot, and with ease. Highlight the cover you want to move to with the camera and hold a key to go there. That simple movement meant I didn’t have to maneuver around a tangle of obstacles, allowing space for more improvisational thinking.

During intense firefights conversations with teammates fell into a natural rhythm based on abilities and weapons equipped. I ran with a semiautomatic shotgun, a cover reinforcing buff, and a turret. In my favorite scenario, two tanky shielded enemies paired with a medic walked up a tight corridor toward our cover. I threw out my turret to distract the shielded enemies, my teammates told me they’d suppress, and I took off to the other end of the corridor to get behind their line of defense, take out the medic, and open up the shielded enemies to fire. If only more of the combat had the same strategic construction.

The Division punishes bad decisions well enough (stay out of cover too long, get shot, or stay in one place too long, get flanked), so it’s disappointing that the elite enemies are just prolonged versions of regular encounters and that they’re used so often. Elites don’t employ especially erratic behaviors, or complex patterns: they just swallow magazine after magazine while talking smack. One of the fights went so long the music ended.

I looked like every other bundled up, sniffly-nosed player out there.

When my teammates and I were around the same level, and played missions at or just below the recommended starting point, the combat was usually a good challenge. We depended on one another to fill out blind spots: I was a shotgunner, so we knew a sniper would be a necessary. If I had the turret and cover buff equipped for flanking, a teammate would spec out a medic class on the fly.

However, incentive to play with one another faded as our levels grew apart. All it took was one teammate a few levels higher than our own to turn a balanced combat experience into their own personal shooting gallery. Conversely, when matchmaking for some of the later missions, I was often thrown into a team of antsy players who were one-hit-and-dead underleveled. Leave that group, and I’m kicked back to the nearest safe house, which is a two-minute sprint back to the mission starting point.

Moot loot

There’s no way to just power through the campaign—where the best level design and encounters are—since they don’t reward enough XP to prep you for the next. Collectibles and killing enemies give out even less XP, which leaves the side missions as the primary gate between you and the best parts of The Division.

Some side missions feed reward points that feed into upgrading your base of operations, a repurposed post office full of repetitive NPCs and visual reward that coincides with newly unlocked perks, combat abilities, and passive abilities. Most boil down to defending a point from enemy waves or infiltrating a warehouse to kill an elite enemy. They take five to ten minutes to complete, running between locations included, which meant I had to dedicate hours to them in order to upgrade my perks and abilities. Even with teammates, no amount of shooting could spare us from the monotony. I’d say we were lucky to find the autorun key, but the implication that we’d need it at all wasn’t exactly a relief.

Weapon imbalances aren’t as frustrating since better ones drop so often, but whether a gun is common trash or an impressive purple drop, they all feel the same to operate, even if they’re crunching different numbers beneath the kimono. The same goes for vanity items and armor. Tom Clancy’s worlds are typically grounded in realism, but without some kind of eccentricity or customizable expression built into the drab wardrobe, I felt my progress was impossible to dictate. I looked like every other bundled up, sniffly-nosed player out there, whether level one or 28.

My GTX 980 Ti had zero problems running The Division at 2560x1440 with settings cranked up. After some tinkering, my GTX 960 at home could run it on medium to high settings at 1920x1080. And there's plenty to tinker with in its full suite of customization, graphics, and control settings.

There were some notable dips when the more expansive vistas came into view, or when multiple objects (or people) exploded at once, but nothing catastrophic. The Division is a well optimized PC game, with the right hardware. Our optimization guide has more details on the settings, with detailed benchmarks.

My attire might have been lacking, but Division’s Manhattan is gorgeous. With settings maxed out, otherwise minute details stand out. Glass, tile, and fabrics shatter and perforate closely to their real life counterparts. Hazy golden hour light spills into the slick city streets, while thick snowstorms turn streetlamps into conical havens and wandering NPCs into creepy silhouettes. A slew of post-processing and weather effects layer on a grimy, sterile palette to a once lively metropolis. Environments are stocked with natural props, one with giant Christmas ornaments, and most can be shot, which make otherwise routine firefights cloudy and frenetic with debris.

But the overarching story is poorly communicated and easily ignorable. It’s a political narrative nested in a game about simple, material rewards, where you’re saving a city by killing half the people in it. In The Division's most discordant moment, a friend and I walked through a scene in the campaign where dozens of coffins and bodies, some covered in American flags, littered the sewers underground. It’s somber scene with scary connotations. When I climbed down for a closer look, it wasn’t to see what I could learn about what happened here, but to see if a loot chest was nestled between the coffins. By the story’s conclusion, hardly anything is resolved, and instead sets The Division up for as many small narratives as it needs for future expansions. But there’s nothing lost by missing the pulpy sociopolitical beats—it’s nice enough as a wash of moody light and sound.

The darkness

At the literal core of The Division is the Dark Zone, by far its most interesting digit, a social exercise in stranger danger. It’s a huge section of the map dotted with elite enemy mobs, hidden chests, and a ton of other players. The catch is that collected loot is contaminated and can only be extracted via helicopter. Every time this happens, all the players in the Dark Zone are alerted to the drop’s exact location. They can help stave off the waves of incoming enemies, or kill you and take your stuff. Doing so marks them as rogue, and ‘pure’ players get a reward for taking them down.

Sometimes, a group would remember my name and hunt me down repeatedly.

Proximity mic chat is enabled, so you can plead for your life, ask strangers to do jumping jacks with you, or coax them into attacking with insults. Sometimes, nothing would happen for an hour and I’d extract loot as a lone wolf without issue. Sometimes, we’d befriend a dozen other players and roam the map like some preternatural loot-extraction force. Sometimes, a group would remember my name and hunt me down repeatedly. That’s what I get for name-calling. It’s unpredictable, tense, and my favorite way to upgrade weapons and gear. But even in the Dark Zone, the drip slowed soon enough, and I was confronted with what exactly to do with my hoard of high level stuff. Not much.

The end game is vapid. Daily missions unlock at level 30, but they’re just campaign levels with difficulty modifiers that reward crafting material, which I’ve yet to find useful. There’s more powerful loot to find, but it all requires serious amounts of repetition to obtain. And afterwards, there’s nothing except the same levels and enemies to test it out on. Free updates are on the way with Incursions, scenarios designed to test players in the end game, but until they’re out the sense of progression is distilled into fleeting number comparisons between weapons that feel exactly the same to shoot.

The RPG-ness of The Division is no more sacred than that of Cookie Clicker’s. Numbers spill out, you collect resources, loot, and make the numbers spill out faster—the RPG components are there for the sake of kill efficiency, increased by little more than a restricted nibbling at The Division’s gristle, a rubbery, tasteless collection of repetitive side missions and heavy health bars. Beneath all the excess is a challenging and strategic eight hour co-op cover shooter that deserves an audience, but it’s occluded by a thick, noxious loot haze.

Boom, headshot! Headshot! Headshot! Headshot. Head. Shot. *sigh*

Environments are detailed and dotted with natural cover.

The Division, directed by David Lynch.

Why the Cleaners are the most fun faction to fight, exhibit A.

Content!

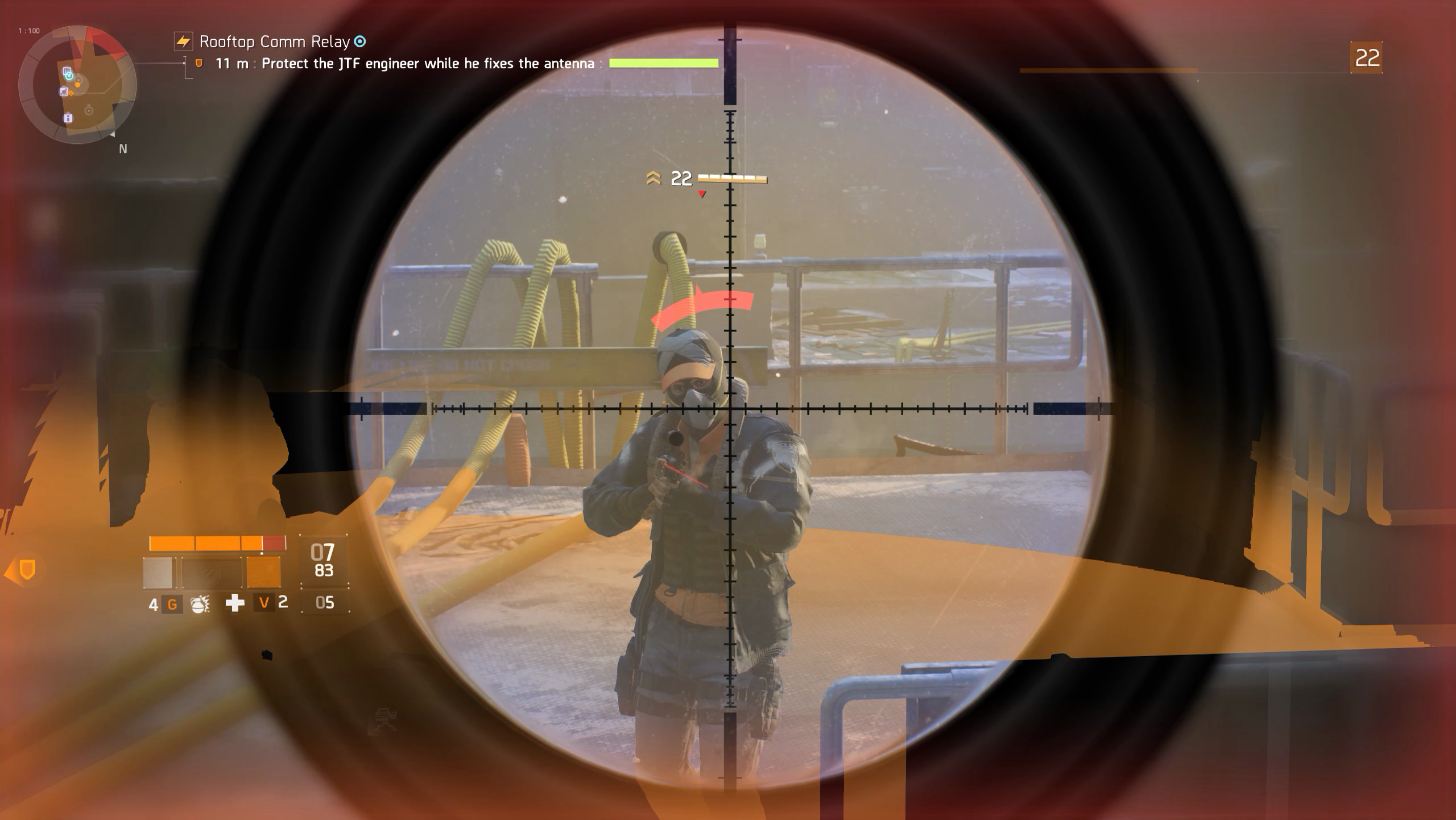

I'm about to get hit.

The leader of the Last Man Battalion, Charles Bliss.

The turret is a reliable ally.

This guy doesn't like the feds. That's his arc.

Iconic locations make for good firefights.

Weather and lighting make Manhattan a moody place.

Winter is hell.

Natural clutter tells its own stories.

The Division is a challenging co-op cover shooter and a gorgeous open world diminished by bloated and unnecessary RPG tropes.

James is stuck in an endless loop, playing the Dark Souls games on repeat until Elden Ring and Silksong set him free. He's a truffle pig for indie horror and weird FPS games too, seeking out games that actively hurt to play. Otherwise he's wandering Austin, identifying mushrooms and doodling grackles.