Our Verdict

A brilliant stealth sandbox and unconventional RPG in one very ambitious but buggy package.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A stealthy isometric RPG set on a prison island

Expect to pay $29.99/£27.99

Reviewed on Intel i5-3570K @ 3.40 GHz, 8 GB of RAM, GeForce GTX 970, Windows 10

Developer Fool’s Theory

Publisher IMGN.PRO

Multiplayer? No

Link Official site

Seven: The Days Long Gone is a collection of genres and settings colliding to create something uniquely unusual. A real-time isometric RPG, a sprawling stealth sandbox, a bizarre post-apocalyptic sci-fi universe with just enough mysticism to make it fantasy-adjacent—there’s a lot to digest. It almost tries to be too many things, spinning all of these very different plates, but developer Fool’s Theory manages to stop them from coming crashing down. Most of the time.

Seven is a game about being a sticky-fingered thief. Specifically, a sticky-fingered thief known as Teriel. A master crook, Teriel finds himself shunted off to the prison island of Peh to be a god-like emperor’s newest undercover agent. His mission: search for an ancient hidden spaceship. Oh yes, and he’s been bonded to a daemon, an extra-dimensional being who serves as an advisor, guide and the emperor’s representative.

In Seven, a thief is not a class—it’s Teriel’s career. So it’s not a set of specific abilities, nor does it limit the ways in which his myriad objectives may be completed. Most missions, whether they’re incidental side quests or one of the core objectives, offer up a multitude of tempting paths.

Say there’s an object that you need to steal, but it’s locked inside a compound and guarded by Technomagi—artefact hunters turned authoritarian police force. Exploring the compound, you might come across a route to the roof and a skylight to drop in from. From there it’s a matter of slowly and stealthily reaching the treasure. If you’ve got a Technomagi uniform handy, however, it might be as simple as walking in the front door. Or you could rush in with swords, energy guns and magic, slaughtering (or knocking out) everyone in your path. Throw in traps, poisonous gas, cloaks, explosives and hacking and your options expand further.

The moment you land on the island, you’re largely able to do everything you can do even 30 hours in, though not necessarily as effectively.

None of these paths are restricted by character builds or experience, either. The moment you land on the island, you’re largely able to do everything you can do even 30 hours in, though not necessarily as effectively. Teriel’s been around the block, so he’s perfectly capable of throwing punches, slitting throats, climbing in windows and unlocking safes. New skills and fancy gear that you can steal, craft or buy still help a lot, of course.

Character progression isn’t tied to abstract concepts like experience points. Instead of levelling up, you beef up Teriel with skill chips and upgrades. These technological augmentations are scattered all over the island—the more you explore, the more skills you’ll unlock. A chip is just a platform that informs what types of skills and upgrades you’ll be able to slot in. Installing them costs nectar, however, and it’s extremely rare. Conveniently, whenever you remove one of them, you recoup its nectar costs.

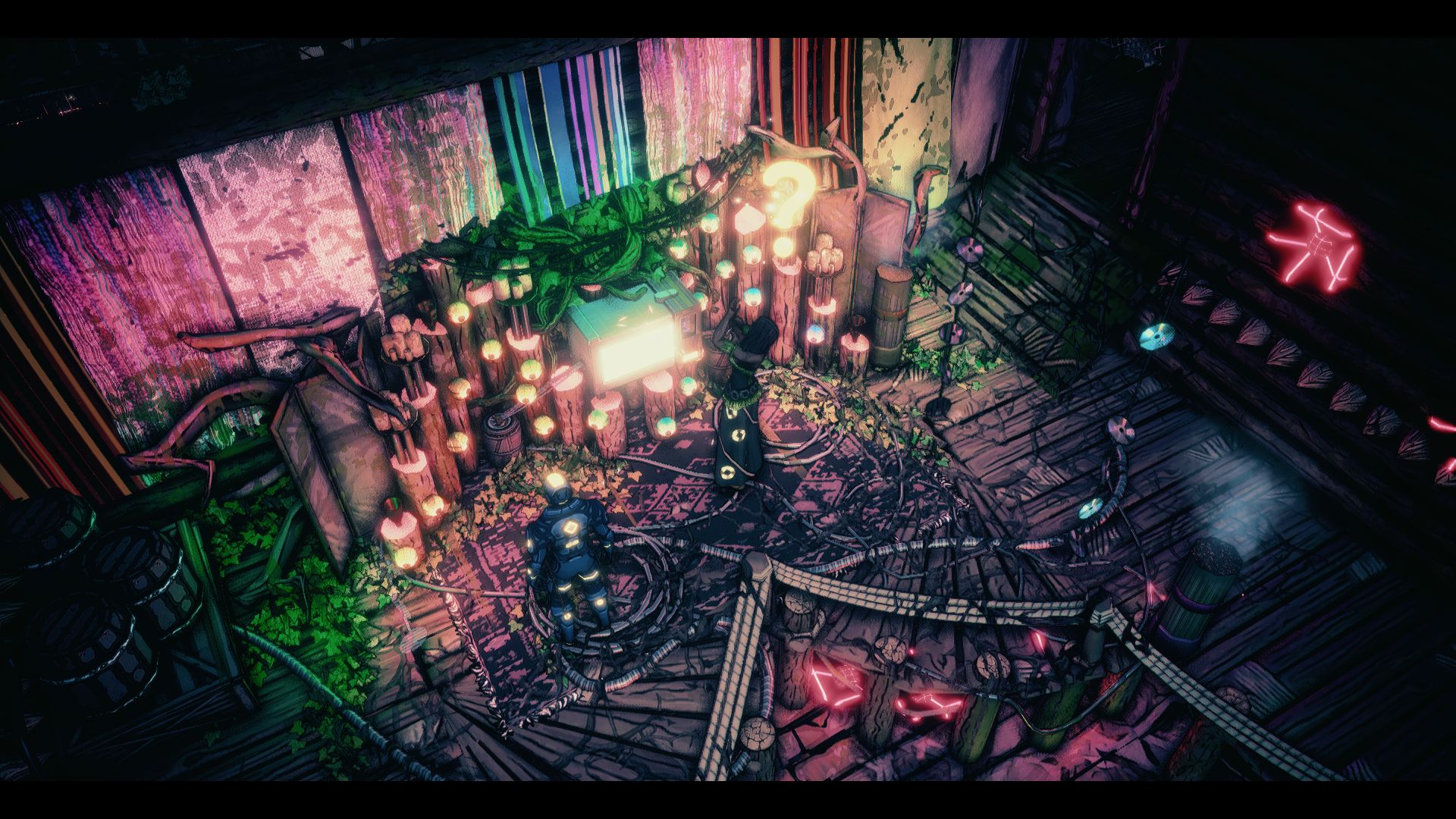

So you can choose whether to use stealth, violence or magic, but you’ll always need to be an explorer. What a relief, then, that Peh is such a compelling frontier. It’s an island that revels in the bizarre. Intimidating military outposts sit next to cyberpunk slums and swampy villages that wouldn’t look out of place in a fantasy romp. And it’s a melting pot of weirdos and ne’er-do-wells, full of criminals, rebels, adventurers, zealots and mages. Walking across the island is like stepping into a new universe every mile. Yet it feels surprisingly cohesive, like structured chaos. Environmental storytelling and the occasional lore dump reveal the strange logic of Peh. It’s a vertical slice of the greater world: a version of our Earth in a far-flung era, set after a golden age and an apocalypse. All that’s left on Earth is the remnants of humanity, those left behind when the ‘ancients’ fled to the stars.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

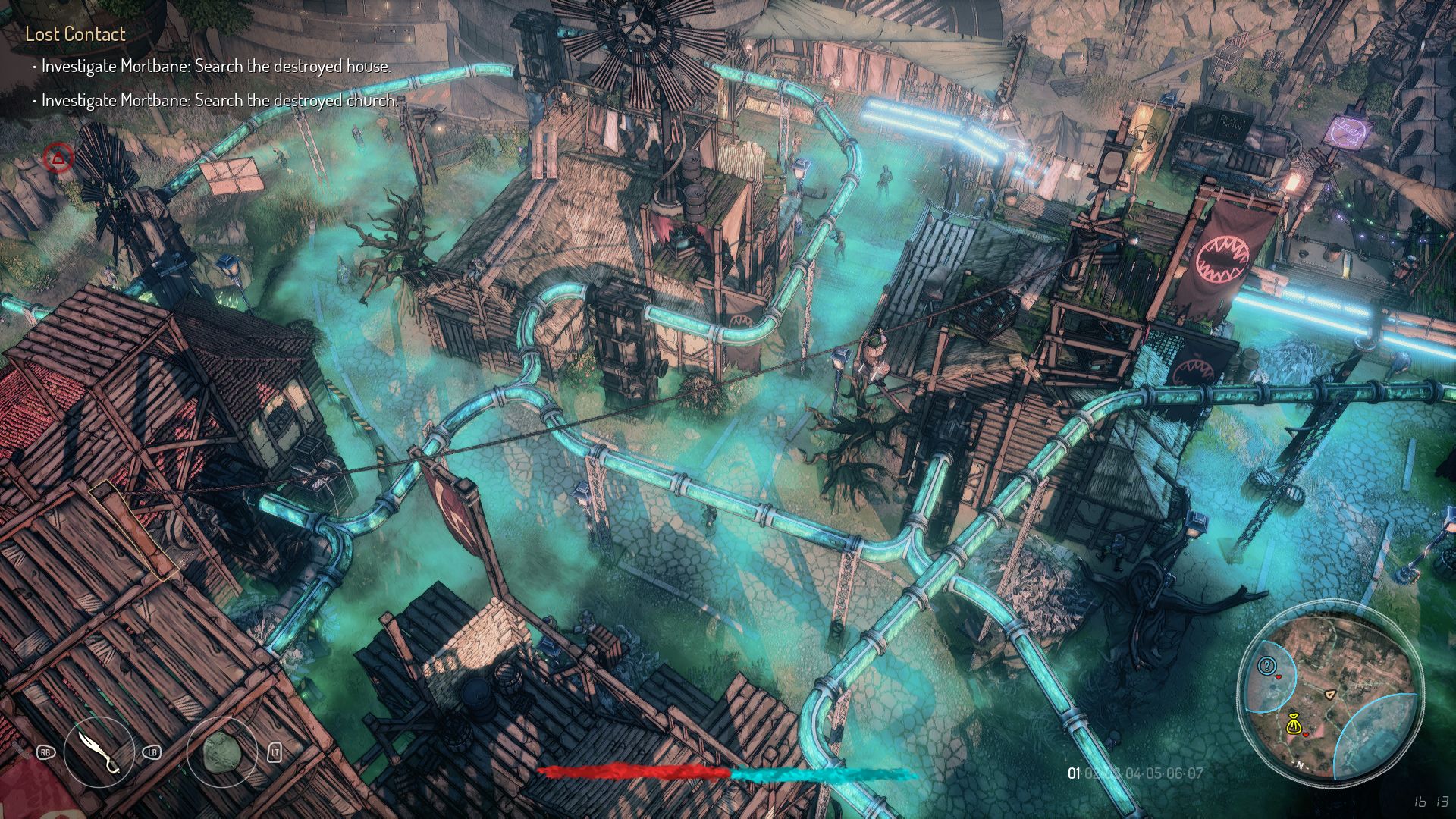

The claim that you can walk from one end of a game’s world to the other right from the start has become trite, but Seven turns it from a marketing talking point into a seductive challenge. The entire island is split up into seven zones, each with a corresponding visa. If you try to get through a zone gate without a visa—which are grafted onto DNA—then you’re going to get fried. And buying a visa is both pretty costly and also sort of like rewarding The Man for being awful. So traveling across the zones becomes an exercise in stealth and guile as you try to get through without using the gate and, more importantly, without getting caught.

Though it’s an isometric RPG, traversal in Seven has more in common with Assassin’s Creed than Baldur’s Gate. Teriel’s nimbler than a cat, and climbing up to the rooftops and beyond is almost as simple as walking down the street. The sprint button doubles as a climbing button so it’s effortless, but it’s also a pain in the arse on those occasions where you’re trying to chase someone but instead climb on top of some barrels. It’s very odd seeing these acrobatic shenanigans in an isometric RPG, but now I’m also wondering why we don’t see it more. It makes every building relevant: a potential bridge to a new area or a way to escape the fuzz. There’s no wasted real estate.

The perspective is obviously a perfect fit for stealth, too. The top down view makes it much easier to plot routes, especially given the ineffectiveness of the map and the generally mad layout of the island’s haphazard settlements, and it lends the game a stronger tactical air, giving you more tools to plan for heists and ambushes. There’s a Detective Mode-style view, as well, which highlights objects of interest, lets you track NPCs and expands your vision. With the multitude of secret items and the sometimes erratic guard patrols, it’s a tool that sees a great deal of use.

Despite this tactical layer, Seven is far from a precise game. I stopped keeping track of how many times my plans fell apart after the first couple of hours. I fell off ledges, got pushed off roofs, rolled into acid, got cornered by hordes of angry axe-wielding cops—if something could go wrong, it went wrong. It’s equal parts stressful and exhilarating. A lot of that’s down to how much stuff is going on in any given area, but the controls could be tighter, too, especially in combat. They’re just a little loose and a little too wild, even if you’re locked onto a target, when there are obstacles and pitfalls everywhere.

With its heaving masses of reactive NPC crowds, very eager guards and complicated multi-level settlements, preparing for the worst is just common sense. Think you’re alone in an alley with your mark? Think again: there’s at least five people watching you from above, and whoops, one of them has just alerted the Technomagi. Better run. Or better yet, leave some traps behind you and enjoy the carnage.

Unfortunately, Seven joins the list of extremely ambitious open-world games that are plagued by some rather serious bugs. I’ve not encountered anything game-breaking, though at least one of them has broken my patience. Seven employs an unconventional fast travel system that, if it wasn’t completely unreliable, I’d be quite enamoured with. Fast travel is limited to a cargo transport network that’s off-limits to everyone but the Technomagi. To use the fast travel stations, then, requires breaking into Technomagi outposts and hacking your way into the network. It’s for this reason that I rarely went anywhere without a full Technomagi uniform in my inventory. It’s a great system that turns unlocking fast travel nodes into an achievement. The convenience is a hard-won reward, not something that’s just doled out. Or it would be if it didn’t stop working all the time.

Whenever I hit up the nearest fast travel station, it’s a total crapshoot. Maybe I’ll be on my way in seconds, but it’s just as likely that I’ll be told by the map that I haven’t unlocked my destination. Saving and reloading usually fixes it, but it’s not a given. The island’s not so large that fast travel is a necessity, but it’s definitely a boon. Similarly, interactive objects, like buttons, will occasionally stop working for no reason. Even the prompt vanishes. Again, saving and loading tends to sort the issue, but it’s an annoying rigmarole when all you want to do it open a bloody door. They’re the most common bugs, but by no means the only ones. There are broken quests and quests that don’t properly update (but can still be completed), attacks that sometimes go right through enemies, clipping that can be exploited by both players and enemies—it’s enough to indicate that Seven needed quite a bit more playtesting.

There are rough edges, then. Some big ones. Yet Seven is still an impressive game, even for a standout year that’s been full of them. And it’s been a bit of a surprise, coming out at the tail end of the 2017 like a dark horse. There’s nothing else quite like it, but it still feels a little familiar, drawing as it does so many classic stealth and RPG romps. It’s like a missing link between immersive sims like Deus Ex and RPGs like Ultima 7 or Divinity: Original Sin 2—weird and liberating and driven by players' whims. A patch or two wouldn’t go amiss, but the pleasures of this unusual game easily outweigh the inconveniences.

A brilliant stealth sandbox and unconventional RPG in one very ambitious but buggy package.

Fraser is the UK online editor and has actually met The Internet in person. With over a decade of experience, he's been around the block a few times, serving as a freelancer, news editor and prolific reviewer. Strategy games have been a 30-year-long obsession, from tiny RTSs to sprawling political sims, and he never turns down the chance to rave about Total War or Crusader Kings. He's also been known to set up shop in the latest MMO and likes to wind down with an endlessly deep, systemic RPG. These days, when he's not editing, he can usually be found writing features that are 1,000 words too long or talking about his dog.