Our Verdict

A brilliantly realised world wrapped around a story-driven shooter that occasionally forgets you want to play it.

PC Gamer's got your back

There's a moment in Metro: Last Light when you get a car – a bodged-together, fortified jalopy – and you immediately think of Half-Life 2's driving sections. Ah, the open road!

The difference is that Last Light's car runs on train tracks. There's something about seeing your future snake off with rigid inevitability that makes it a particularly easy metaphor for Last Light's frustrations: sometimes it feels like an on-rails shooter in every sense.

Those are just lulls, however. Elsewhere it's a game of gratifyingly kinetic gunplay, intense stealth sequences and a stunning, bleak vision that rivals the imagination of even BioShock Infinite. Its stage-managed linearity cuts both ways, too, enabling Last Light to draw a world of incredible detail, carefully framing sights and scenes of postapocalyptic tragedy and chaos. It describes humanity with a degree of success that few games of any genre achieve, much less shooters.

"It describes humanity with a degree of success that few games of any genre achieve."

Set in the nuclear-shielded Moscow subway system following a devastating global war, Last Light's story picks up where Metro 2033's ended. You once again play Artyom, now a newly minted member of the Order – a sort of subterranean Night's Watch, formed from ex-Spetsnaz soldiers. Two important things have happened: with Artyom's help the Order has located and taken control of D6, an experimental weapons facility likely to become the envy of the Metro's other warring factions. Secondly, Artyom has just used the missiles within D6 to commit genocide, obliterating a race of benign mutants who had the poor luck of being 12-foot-tall wormy-mouthed psychic ape-monsters whose mere presence causes men to die in terror and pain. Because of the stigma attached to being a telepathic death beast, not everyone is convinced of their benevolence, and when one is discovered to have survived the holocaust, you're dispatched to kill it.

What then follows is a nightmare version of Mornington Crescent, taking Artyom on a circuitous round-trip through the desolate tunnels of the Moscow subway system, along underground rivers, into military bunkers and other even darker places. Human existence here is precarious, and even a short trip between pockets of civilisation feels suitably dangerous: dereliction and nuclear destruction have left the tunnels in a bit of a shabby state, while gruesome mutants stalk the black halls and the sad, shattered city above is haunted by things even weirder and more worrisome still.

"Human factions tussle over the scant resources, or vie for Metro-wide domination"

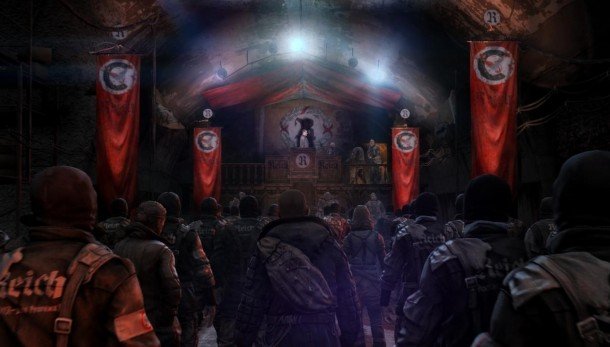

Worst of all, other human factions tussle over the scant resources, or vie for Metro-wide domination. Nazis and Communists have carved out portions of the railway system for themselves, one establishing a Fourth Reich bent on eradicating mutation, and the other the Red Line: a literal line of track that bisects the entire subway system.

It's an incredibly well-fleshed fiction, and Last Light's most tremendous success is the way that it communicates this world, visually and narratively. The overall arc of Artyom's story is, oddly, the least thrilling thing about it – the plot beats are predictable and Artyom himself is a bit of an empty shell. You do get a sidekick every now and again who is worth his weight in dialogue, but even these characters are lightly sketched. However, if nothing else, this story is a conduit for delivering the intoxicating, forbidding Metro itself – and that's worth the price of admission. The echoing warren of tunnels creates a powerful and oppressive feeling of enclosure and decay: lights sputter and surge, concrete walls crumble or run with water. Groans, mutters, creaks, clanks and drips ripple up and down the long black tunnels. The austere militarism of a nuclear bunker segues into the grimly functional tube network and the art deco opulence of the stations – all now rotting or reclaimed by nature.

Death is everywhere – I can only imagine that the developers, 4A Games, have an entire department dedicated to corpses. There are so many, animal and human, and in so many varied states of exquisitely studied decomposition. It starts to lose its shock: death becomes an all-pervading force, a simple, grim inevitability. Metro is, I found, rarely as scary as it is sad.

"Metro is, I found, rarely as scary as it is sad."

Things aren't much cheerier above ground. The toppled skyline of Moscow has a grim sort of majesty to it, but it's colonised by a bloodthirsty ecosystem that harries your every step, ripped at by winds, whipped by rain and crumbled into pools of irradiated slurry. It all feels rather like you aren't meant to be there – which is entirely the point.

The only places where mankind still thrives are the underground stations, each its own semiautonomous city-state. It's here that 4A go to town on the scripting. Each station looks incredible, but they are essentially galleries, and each cluster of people in them a separate exhibit, triggered one after the other as you follow the prescribed route. An elderly man makes shadow puppets to entertain a gang of kids, but none recognise the pre-apocalypse animals he's describing. A soldier strums a guitar while a pair of civilians bicker with an officious guard. Dancing girls with improbable breast physics do their thing and hoodlums scour the docks, shaking down whoever they can. Not all the voice-work does it justice – the children, in particular, are dreadful – and the ludicrous, non- Newtonian mammaries really stick out (ha) in a game otherwise drawn with such consistency. All the same, the hubbub of personal stories is so captivating that you almost forget that your consumption of it is essentially passive.

Almost.

There are a few minor opportunities for interaction in the hubs, but they are largely just for show. And that's fine, but after a while, the part of my brain that craves interaction grows impatient. It's not simply that it's linear – in fact, Last Light has more incidental details and siderooms to explore than most shooters. Instead, a mixture of game-balance and scripting works to trivialise your input. Early on, there was a period of an hour or more in which I felt like I'd done little but follow people between doors. Even the momentary bursts of combat here were given scripted conclusions that made me wonder if I'd wasted my ammo, or bundled me into cutscenes I was powerless to affect, or were restricted to tactically-void turret sequences or wave-survival.

"When the stealth and combat systems are finally allowed to blossom, Metro: Last Light is riveting."

Some of the early stealth sections are so easy that I felt irked to miss out on potentially entertaining combat. Throwing knives make things simpler still: they fly straight, kill instantly and silently, and can be retrieved from corpses to give you an infinite supply. The game barely seems to resist your forward momentum: even open confrontation poses little threat on normal difficulty, and you'll rarely find yourself running low on supplies. The first game had a clever, if overly fussy, economy: militarygrade bullets were a currency but also significantly more deadly than the plentiful crappy ammo for which they could be exchanged. The same is supposedly true here, but on normal difficulty I never found the power of my weapons wanting, or really any need to buy ammunition at all – more than enough was available to scavenge. On the harder difficulty, combat becomes appropriately lethal, and resource management more important, but the trade-off is that the game's duff bullet-sponge boss-battles become a right old slog.

When the stealth and combat systems are finally allowed to blossom, Metro: Last Light is riveting. Humans are still the most fun to fight, and the most exhilarating encounters are the ones that give you a chance to whittle down the opposition using stealth before forcing open combat in large, multipathed arenas. The dark is a powerful ally – almost ludicrously so, enabling you to stand directly in front of someone without being detected – and many of the battles begin with a gentle puzzle element as you work out how to reach circuitbreakers and deactivate the lights. Enemies come equipped for such situations, and will flip on headmounted torches while sauntering over to check the breaker box, forcing you to flee into cover as their torch-beam flits across the room.

The score rises to a trumpety shriek as you are exposed by light, giving you the briefest moment to retreat back into dark – if indeed you want to. After all, what's the point of carting all that ammo around if you don't get to shoot it into people? It would be a particular waste given your arsenal's enjoyable variety and uniform heft. Even when silenced, the pistol feels potent and mean, spitting out beads of death with a contemptuous 'phut!' Each weapon is upgradeable and customisable, letting you choose between a number of sights and scopes, and giving your three weapon slots an enticing tactical flexibility. I spent most of the game slinging a silenced pistol with a telescopic scope and laser sight, a night-vision-enhanced assault rifle and an absurd fourbarrelled shotgun – a handy deterrent for the game's swarming mutant enemies.

"Mansized mole-mutants have been given an animation overhaul that gives them a scuttling, vicious guile."

One of Metro 2033's weaknesses was its monster design, being neither especially threatening in appearance nor entertaining to fight. Both aspects have been vastly improved here. The bounding packs of mansized mole-mutants have been given an animation overhaul that gives them a scuttling, vicious guile. And no longer do they just plough into you in a suicidal stream, instead opting to lash at you from multiple sides, or hanging back before closing the distance in a single ferocious leap. Spidery horrors burn in the light, creating a crowd control problem as you try and concentrate your beam on one of them long enough to inflict damage, while keeping the others at bay.

They still don't have the AI behaviour that makes the game's human opponents a joy to manipulate, but Metro's monsters serve to panic you rather than tax you tactically. Though to a blessedly lesser degree than in Metro 2033, your vision is constantly under assault, and this is most true when scrapping in a melee. Visors crack or bead with condensation or blood. Putting your shotgun to a beast at close range will spatter you with jam, which you'll have to smear away with the tap of another button. It's one of the many small make-work tasks that keeps combat a frantic act of multitasking. If you're underground, the chances are you'll periodically need to crank a handheld charger kit to stop your flashlight sputtering out, or to keep your night vision goggles powered. If you're overground you'll need to keep an eye on the clock, changing your gas mask's filters every five minutes, or replacing it entirely if damaged.

This was a source of extreme tension in the previous game, largely because the signposting of its external sections was so poor it was easy to asphyxiate while scrabbling against one of the level's invisible walls. Last Light makes sure you have a fairly generous supply of filters at all times, and although this takes some of the terror out of your overground excursions, it does at least mean the game avoids boxing you into a fail state. It's also a relief in the game's more open environments, which still don't do a great job of telling you where to go, but are quick to punish if you try something the designers don't like.

"you can climb over a low wall if it's part of the path laid out for you by the designers, but other walls thwart your efforts."

In part this confusion is intentional – you are meant to find the route yourself (and if you've been paying attention to incidental conversations, you may have a hint or two to help you) and you are meant to feel panicked by the vague notion of time pressure. But there's not quite enough consistency to the design to stop this being annoying: you can climb over a low wall if it's part of the path laid out for you by the designers, but other walls thwart your efforts, even though they might look like a happily navigable route.

This is especially true of a section in a swamp, where stumbling into a pool of water can mean instant death. The game doesn't allow saving, it uses a checkpointing system instead, and it's not especially sympathetic to your predicament. I had to restart the entire chapter when the game checkpointed me at the bottom of a riverbed.

By and large, however, the checkpoints neatly punctuate short bursts of action and that was one of the only times I felt punished by the lack of a save file. Nonetheless, it seems like a needless omission, and I'd like to have kept a few personally timestamped saves so I could go back and try different approaches to the same battle. Because: why wouldn't I?

"When it's all working perfectly, Metro: Last Light assembles a forlorn and beautiful world."

The checkpointing system, and, I suppose, the low default difficulty, are the only two bugbears imported from console land. The game has plentiful graphics options, letting you tweak vsync, motion blur and tessellation – but not FoV, presumably to maintain the necessary sense of claustrophobia. My review machine runs on an i5 with a GTX 560 Ti, and, unsurprisingly, it devoured the game. It's also relatively glitch-free - I had a few very rare issues where I was spotted through scenery or immobilised during a context-sensitive animation. More entertainingly, at one point all the children's faces contorted into terrifying beaks.

When it's all working perfectly, Metro: Last Light assembles a forlorn and beautiful world, and your journey through it takes in many poignant, delirious and terrible sights. When you get to wield some autonomy, the game creates brilliantly panicky, desperate gun battles and heart-in-mouth stealth escapades – but it's worth it for the ride, even when your hand isn't always on the tiller. We'll just have to keep hoping for a game where the scenes of highest drama are played by you rather than before you.

A brilliantly realised world wrapped around a story-driven shooter that occasionally forgets you want to play it.