Ultima Underworld transformed first-person games forever

Reinstall: Ultima Underworld - The Stygian Abyss.

This article originally appeared in issue 246 of PC Gamer UK.

My memories of Ultima Underworld are of an endless stream of delighted discoveries, an abject fear of what might lurk in the dim and tortuous tunnels, and of scribbling notes about which NPC wanted what item and which rune sequence created which spell.

Jumping back into the sprawling dungeons of the Stygian Abyss today is gleefully exciting. But it's also a tiny bit depressing, because I'll never get to play it for the very first time again.

Not only was this the first 'proper' PC game I ever played, but also one of the most influential PC games in terms of technology and design that has ever been released. Like its Ultima predecessors – in spirit if not in mechanics – Underworld was a genuine RPG, stuffed full of quests and magic and exploration and dialogue and weapons and stats.

Back here in the present day, I'm playing a Fighter, right-handed, swimming speciality, Str 11, Dex 8, Int 6 . And I'm struggling to move. Fortunately there's a tutorial of sorts to follow – in the manual. This was an age when you actually needed to read them.

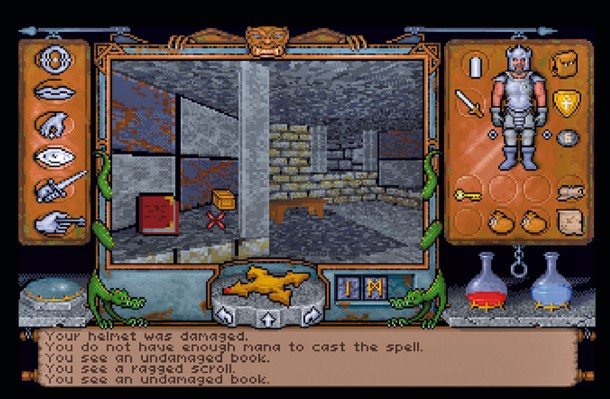

Underworld was one of the first games to offer genuine real-time 3D movement and combat, as well as mouse control for changing the view. Thing is, it's not the now-standard mouse-look model. Instead, you click near the edges of the screen to rotate your view, and near the middle to move forwards. It's like Dungeon Master but in real time. And to complicate things, you have to click icons at the side of the screen to choose how to interact with the 3D view: Examine, Use, Pick Up, Talk and so on.

It takes some getting used to, particularly if you haven't played an older game like this for a long time, but after a while it's manageable. Use the keyboard controls for moving and the mouse to turn, and you're golden. I was soon rediscovering the sense of sheer exploratory joy that's baked deep into Underworld.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

I mean, bloody hell! Underworld's eight massive levels, each almost a game in itself, are proper 3D environments, with angled walls and floors, and ledges, chasms and lakes. You can run and jump and swim, and even levitate. You can look up and down, for God's sake. There was also genuinely groundbreaking texture-mapping, which transformed the way videogame graphics looked forever.

As well as being genuinely exciting technical innovations, all these things made Underworld a fundamentally different experience to the then-standard 'move one square forward/back/to the side' affair. Most importantly, it gave you the sense of being in a real environment, not just a grid-square map of locations. For the first time you had to take into account vertical architecture as well as horizontal, while the ability to jump and fall let Underworld introduce puzzles which required you to properly explore the space. Fantasy battles could be epic affairs for the first time, where you leapt about on tables and ledges to get a height advantage – not just you standing there bashing the Attack button and waiting for the enemy to take their turn.

It's difficult to overstate just how many innovations Underworld brought to the genre, but it was what I was actually doing in the game that hooked me. Even at a time when complex, massive RPGs were the norm, it was exceptionally engrossing. I still have my notebook; it says things like 'Sir Cabirus: eight talismans', 'Ironwit wants blueprints – SE of his complex?' and 'Uus Por: large jumps', along with translations of a lizardman language and other long-forgotten reminders to myself.

'Uus Por' was a spell I'd discovered: in Underworld, you cast spells by collecting individual rune stones you find in the dungeon, then arranging them on your rune rack. Some of these spells you can find written down, others have to be discovered through experimentation.

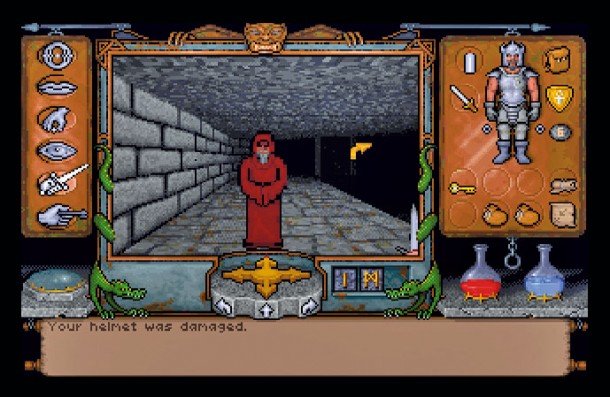

Each of the eight levels of Underworld is artfully designed. As you descend deeper, you're introduced to more and more factions. There are the goblins, of mutually hostile green and grey varieties; the lizardmen, with their seemingly impenetrable language; an order of knights described by the strategy guide as 'depressingly virtuous'; and the usual ogres, trolls, ghouls, mages, bats and more.

They all have stories that intertwine in mini and major quests, with goals often covering multiple levels, so it's vital to keep track of what's going on. There's no quest list, no XP, no levelling up, no choosing new skills every now and then; just a coherent, contiguous, living world and whatever you can find in it to survive.

For me, then, Underworld is almost the perfect RPG – control issues notwithstanding. It has influenced, directly and indirectly, the Elder Scrolls series, the Deus Ex games, Half-Life 2, System Shock (Warren Spector was the game's later producer), BioShock, Tomb Raider, and frankly just about every 3D RPG that has since appeared.

So I'm still baffled by the relative lack of interest shown in it over the years. There was a sequel – bigger, more polished, but ultimately less inspired – and that was it. [We don't talk about Underworld Ascendant – Ed.] Yet maybe more than any other classic PC game, Underworld is crying out for a remake. Don't touch the systems, the content, the story or anything else, just modernise the graphics, jiggle the control scheme a bit and you have the RPG to beat all RPGs. It makes Dark Souls look like Angry Birds.

Of course I know this is never going to happen – EA own the rights, for God's sake – but I can dream. And in the meantime, I can revisit that sodding knight on level 4 who kicked my arse 20 years ago.