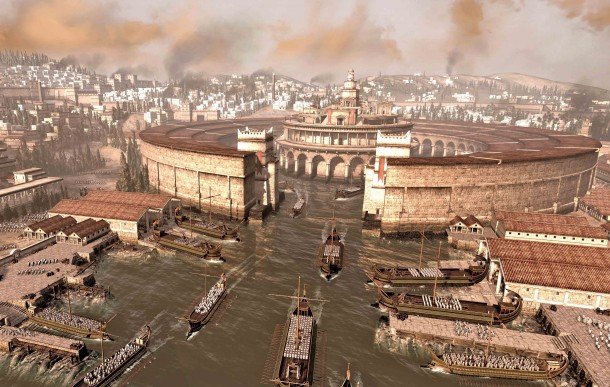

Rome 2: Total War preview

This article originally appeared in issue 247 of PC Gamer UK.

Creative Assembly's Total War team is now almost four times larger than it was when developing the original Rome: Total War. Player expectations have advanced in tandem with technology, and the bar keeps rising: from Shogun's jagged sprites to Rome II's grime-streaked, battle-hardened soldiers, there's always more that can be done to render historical warfare with the depth of detail that has come to define the series.

For Rome II, Creative Assembly have divided their developers into cross-disciplinary 'functional teams'. Lead designer James Russell explains that individual aspects of the game – battles, the campaign, multiplayer – are being handled by small groups of programmers, designers and artists working closely together.

“You have multiple small teams, and you keep that small-team culture,” he explains. As the level of detail has increased, so the boundary between each of these disciplines has shrunk.

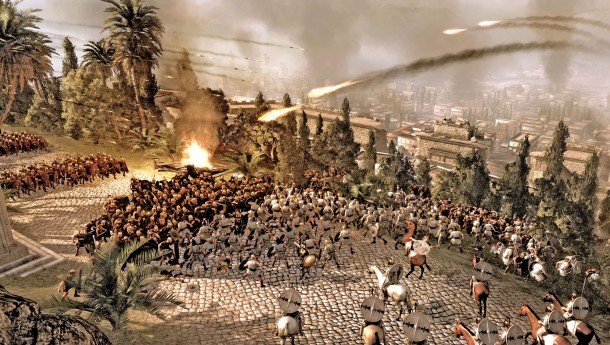

“We simulate things,” Russell says. “For example, the projectile system – it's fully simulated, and that's a really big deal. From a professional perspective, people might think that we're crazy to do that. In a typical RTS, you might say that in a given situation there'll be a specific kill rate.

“If a target enters cover you'll apply a modifier rule to the kill rate – minus 20 percent or whatever it is,” he adds. “Because we're a simulation, the kill rate is determined by whether the arrow hits or not. Whether or not cover affects the kill rate is a property of that cover – it's not in our control, directly, and that's really scary for a designer.

“But it does mean that you get all of these interesting properties of reality falling out for free. You don't need to create a gamey rule.”

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

In order to balance a system like this, Rome II's designers need to go back to the properties of real life – not the abstractions of wargaming. If men taking cover behind a line of rocks are dying to arrow fire faster than is desirable, then the solution has to come from the whole team – whether that's a designer tweaking the accuracy of bowmen, an artist redesigning the scenery, or a programmer tweaking the behaviour of the AI.

As much as Creative Assembly have stressed drama and spectacle in the early marketing push for the game, Russell is keen to point out that building a detailed presentation of war is a crucial part of improving the game's tactical depth.

“Our battles feel realistic, in an intuitive sense,” he says. When troops clash on the battlefield, in other words, the player shouldn't see a mathematical formula resolving itself: they should see thousands of individual people acting and responding according to the orders they've been given and the events around them. “You don't want to see the hand of the designer, in that respect, because you want it to feel like it couldn't be any other way. Real-world tactics should win in the game.”

Creative Assembly's state-of-the-art motion capture facility is hidden on the edge of a railway yard in west Sussex. It is, they believe, the largest developer-owned mocap suite in Europe – and the culmination of years of work on the part of their animation team.

For any other developer a facility like this would be a tremendous extravagance, but Creative Assembly can be confident in the fact that they will always be working on Total War games, and that they will always have a need for detailed and realistic depictions of men murdering one another on the battlefield.

The early build of Rome II that we've seen in action uses a fraction of the capture work that will go into the final game, Creative Assembly tells me.

Everything from simple marching animations to choreographed 'matched combat' sequences between two or more fighters will be pulled from a vast pool of data, breaking up the monotony of the battle line and investing each combatant with their own personality.

Then, as the dramatic actions of those individual troops propagate up through the simulation, Creative Assembly hope that the new level of detail they can achieve will pay dividends for the game as a whole.

“We want to have our cake and eat it,” Russell admits. “On the campaign map, we understand that it's a game of statecraft – but we want to make you feel that you're running an empire that's populated by real individuals, and that you're negotiating with AIs that feel like real people. It's about making the game feel massively enhanced at both ends of the scale.

“I think those two things actually reinforce each other,” he concludes. “That's the point. We want to take what we've learned and use that to push every aspect of the game forward without compromise. It's really scary. It's a really ambitious project. We've got a motto: 'If you're not shit scared, you're not trying hard enough.'”

Joining in 2011, Chris made his start with PC Gamer turning beautiful trees into magazines, first as a writer and later as deputy editor. Once PCG's reluctant MMO champion , his discovery of Dota 2 in 2012 led him to much darker, stranger places. In 2015, Chris became the editor of PC Gamer Pro, overseeing our online coverage of competitive gaming and esports. He left in 2017, and can be now found making games and recording the Crate & Crowbar podcast.