BioShock Infinite hands-on: five hours in cloud city

There's something I can't tell you about BioShock Infinite. Not because it's a spoiler – I'll avoid those too – but because I can't quite communicate it. It's something I felt after playing Half-Life 2, and again after playing BioShock 1. It's the sense you get after experiencing something so vivid and rich that you know you'll never be able to fully describe what it felt like. But I'll try.

"'City in the clouds' doesn't really express the sheer size of it: there seem to be several of those in every direction."

That's not how I expected to feel after playing Infinite for the first time. They'd kept it out of journalistic hands until suspiciously close to release, and the trailers and walkthroughs didn't give a good sense of what kind of game it was. Somewhere in my head, I just copied BioShock 1 from the bottom of the sea and pasted it into the clouds.

Some of that is accurate. In BioShock 1, you played an outsider discovering a failed utopian city at the bottom of the sea; in BioShock Infinite, you play an outsider discovering a failing utopian city floating in the sky. Both games let you explore an extraordinary place, piecing together its story from evidence left lying around. And both games alternate that with combat: you wield both conventional guns and a suite of basically-magical powers that let you do interesting things to your enemies.

Once you arrive, though, it's hard to call them similar. 'City in the clouds' doesn't really express the sheer size of it: there seem to be several of those in every direction. Columbia's huge districts are disjointed, drifting in loose formation as the impossible flotilla tours the world. The first one I explore feels disjointed in itself: half the buildings seem to be bobbing and lurching independently, like some weird dream. Curving skyrails take massive carriages of cargo, like sidewinding trains. Airships propel themselves slowly between districts on twin fans. And the smoke from every chimney streaks in the same direction: we're moving.

But the most startling difference from BioShock 1 isn't the views: it's the people. Rapture was a failed utopia, Columbia is still very much in the process of failing.

"Exploring a dead place by yourself, with you being this cypher, we've kind of done that."

Plenty of times in my five hours, I'd enter a new district of the city where no-one has any particular reason to hate, fear or shoot me yet. Columbia is full of civilians milling around, gossiping, griping, and going about their business. It's exactly what Irrational Games had avoided doing not only in BioShock, but in its spiritual predecessor System Shock 2, simply because it's so hard to make it work. I asked creative director Ken Levine: what changed?

“If we went back to that now, I think people would say we were just repeating ourselves. Listen, it would have been a lot easier. We would have been having this conversation two years ago... but exploring a dead place by yourself, with you being this cypher, we've kind of done that.”

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Was it as hard as they feared back then? “So, I don't want to bore you with my problems, but the writing task was monstrous. It was huge. I remember the first level I wrote, the first draft for this prologue, I sat back and looked at this script, and I realised this script alone was longer than my entire script for BioShock.”

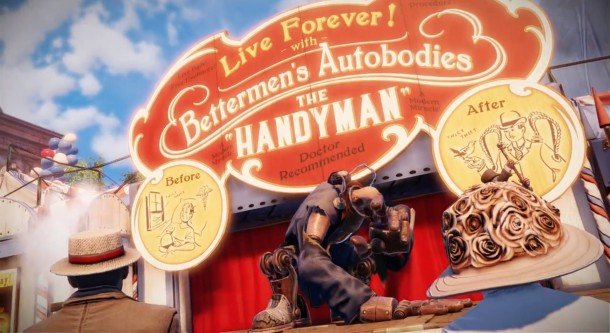

As I'm playing it, though, it's not a game of long conversations. A lot of that work seems to have gone into a depth of story, rather than length. Even more so than in BioShock, the density of information encoded into the world around you is overwhelming. Every poster is propaganda for a faction you'll meet, or a product you'll buy, or a cryptic hint to one of the game's dozens of connected mysteries. Pre-television viewing booths show flickery greyscale government infotainment, with title-card dialogue and jaunty music.

"Almost every line of dialogue has some payload of information about this foreign place."

Plot characters still leave audio diaries of their thoughts lying around, but now they're joined by living people having normal conversations. And almost every line of their daily lives has some payload of information about this foreign place.

“It's damned inconvenient when buildings don't dock on time,” a well-dressed man complains to his companion as I walk by. “Yesterday I had to take a gondola, rubbing shoulders with all sorts.” If you're 'someone' in Columbia, your destination comes to you.

Later on, I actually see it happen. As I'm walking towards a bridge, Chas White's Home and Garden Supply shop floats slowly towards me and docks noisily with a pair of metal teeth jutting out of the street, clanking into place and steadying as it locks. A nearby troupe of a cappella singers harmonise over the noise.

It's all terribly... nice. It has the atmosphere of a cheerful village fete, but in a village that couldn't exist. At one point, we seem to be in a cloud: a thick haze turns everyone in the street to silhouettes, picked out by spectacular rays of golden sunlight. Confetti floats through the air, and hummingbirds pause to probe flowers. Two children splash each other in a leaking fire hydrant.

"Blood geysers all over my face. I'm drenched. Everyone's screaming."

Half an hour later, for reasons I won't go into, I'm ramming a metal gear into a man's eye socket until blood geysers all over my face. I'm drenched. Everyone's screaming. Four more men are coming for me, and this blunt steel prong is all I have to kill them with.

I skipped ahead there for two reasons: one, I don't want to spoil why violence does finally break out in BioShock Infinite. It's a moment that will become notorious in gaming, and a hard one to forget.

Two, I wanted it to sound jarring, because it is. Extremely, intentionally and upsettingly so. When I ask Ken about it, he describes the intended effect as “biting into an apple and finding the worm at the core”.

It works as that. But it's also jarring in another way. A moment ago I'd been enthralled by this place, fascinated by how different and fresh it was, hanging on every word of these people's everyday lives. When I realised my next task was to ram a piece of metal into eight different people until they were all dead, part of me thought, sadly, “Oh yeah. Videogames.”

It's not a new thought, it only stands out here because Infinite is so superb at conjuring this place and luring you into its story. When I mention it to Ken, he's sympathetic. “It's an intensely bizarre concept that you play a character – whether it's Uncharted, or this game, or even like an Indiana Jones movie – who's essentially a psychopathic mass murderer. You're fucking insane. I'm very aware of this issue... it's something we actually attempt to confront at some point.”

"It's strange to see white-on-black discrimination so unflinchingly depicted."

The other thing Infinite confronts, with surprising directness, is racism. I'm so used to games having some orc- or elf-based analogue for it that it's strange to see regular white-on-black discrimination so unflinchingly depicted.

“I didn't want a game that just had some racism in the background,” says Ken. “I wanted you to be engaged and confront those issues – in the same way we confronted you with what capitalism does when it goes to its maximum extreme.”

“In this game we think it'd be honest to deal with these topics, and these aren't topics we take lightly, and they're not necessarily going where you think they're going. This is not... I don't want to spoil anything.” Well, mission accomplished.