Our Verdict

The promise of VR is thrilling, but the experiences the Rift enables right now are just scratching the surface.

PC Gamer's got your back

I still have moments in the Rift when I forget myself. In a flash of frustration or pure brain commitment, I take my hand from the controller and reach for something that isn’t really there. But I can see it. It feels real. Maybe, just maybe, some part of me thinks, if I reach for it, I can touch it. I can grab it.

I can’t, of course. The Oculus Rift is a portal to another world for the eyes and ears, and for the mind, but not for the body. Not yet. But it’s come so far, so fast, from the prototype on Kickstarter a few short years ago. And now it’s a new platform for playing games that I slip on every day—partially for fun, and partially to wrap my head around the totality of the Oculus Rift experience.

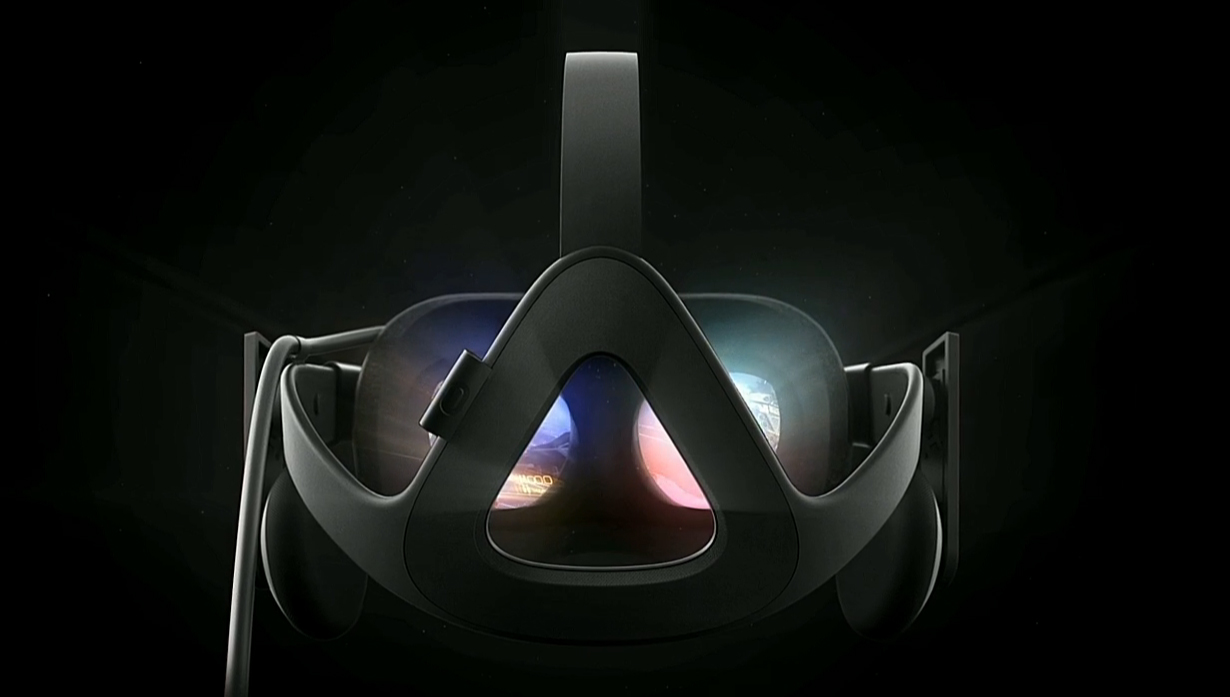

Reviewing the Rift means playing a lot of games. It means considering the design of the hardware. How it fits my head. How comfortable it is. How its lenses and screens serve the games they display. But it goes beyond that—it means thinking about VR as an entirely new way of playing games on the PC, and how the Rift heightens or hinders that experience. Not just the mechanics and fun of dogfighting in EVE Valkyrie, but how swooping around asteroids and using my head to aim lock-on missiles makes my brain feel, and how it utilizes this new technology. How true immersion—the kind of immersion that tells your brain not to step off a ledge, because it truly believes you will fall—can change how we experience digital worlds. And what it means for all of those things to be "worth" the buy-in price of $600.

For the past three years, the promise of VR has been bold: nothing short of a paradigm shift in how we interact with technology. For Oculus, this is presumably just the beginning, the first step on a long road of technological progress. For game developers, too, this is just the starting line of a race to design games fundamentally unlike anything we’ve played before.

The sense of potential has been the defining characteristic of my Rift experience so far. The arrival of VR is hugely exciting, but the games and technology available at the start of this journey struggle to keep me in the headset for more than a few minutes at a time.

Into the Rift

Oculus designed its setup process to be as simple as possible, and that degree of care extends to the entire process of using the Rift. A single cable reaches out of the headset before splitting into HDMI and USB at the base. The software is designed to be an always-on Windows service that uses the Rift headset’s light sensor to detect when you’ve put it on, at which point it smoothly launches the Oculus Home software (this decision has led to a privacy outroar about how the service can access your PC's data—the policy reads like standard disclosure language to me, but Facebook obviously loves personal data).

Home itself is easy to use with either the included remote or Xbox controller while in VR, with a simple library setup and large thumbnails for games (although some of these are so busy, they can be tough to read). Part of Oculus Home’s simplicity, however, means there are some missing features. The software at launch can only install games to the C:\ drive, an antiquated requirement that Oculus is aware of and will hopefully fix in the near future. The lack of social features is simply baffling for a new platform in 2016. Oculus has a friends list, but no way to send messages or voice chat with your friends. You can only see that they’re online and in a game or not, and send an invite if you’re in a multiplayer game yourself.

To coordinate a multiplayer session of EVE Valkyrie, I ended up taking off the Rift multiple times to send text messages, then taking it off again when Valkyrie’s voice chat kept cutting in and out so I could set up a Skype call. Being able to easily coordinate a party of friends and voice chat seems like a day one necessity for a new platform in 2016, especially when Oculus wants to push the concept of VR as a social experience. It’s especially a shame because the Rift has a stellar microphone.

When I put on the headset, I look at that list of games, and don’t feel compelled to play many of them.

Mostly, though, Oculus Home is a means to getting into games, and those are the experiences that justify buying and wearing the headset. The Oculus Rift’s 30-strong launch lineup contains quite a few ports of simple games from the GearVR’s library. Most of them are entertaining for a few minutes. But most of them feel slight, the kind of library padding you’d use to show off the Rift to a friend—”hey, check out this neat thing”—and quickly move on from. When I put on the headset, I look at that list of games, and don’t feel compelled to play many of them, let alone recommend someone spend money on them.

We've written about most of the Oculus Rift games we've played in more detail here. We'll be writing more standalone reviews in the weeks to come.

Pre-order pack-ins EVE Valkyrie and Lucky’s Tale are among the standouts, but even those aren’t compelling cases to buy the Rift, to me. As Tom wrote in his Lucky’s Tale review, there’s a surface level charm there, but nothing deeper to bring Lucky up to the level of a Mario or Banjo Kazooie. There’s proof here that platformers can be awesome in VR, making you feel like you’re inside this world and helping judge depth in 3D, but the game itself never pushes beyond platforming basics. EVE Valkyrie’s dogfights can be thrilling, but a poor menu interface makes everything outside combat a chore, and combat could benefit from some teaching tools baked into its design: a killcam to show you how and why you died, stronger encouragement to work together as a team.

Of those 30 games, many are enhanced by VR. BlazeRush’s miniature cars take on a charming toy-like quality. Radial-G’s gravity-bending F-Zero-style racing becomes thrilling and intense (and stomach-churning if you’re at all prone to motion sickness). Pinball FX2 feels much closer to playing a real pinball table in VR than on a TV. But VR doesn’t feel essential for any of these games. The more time I spent with them, the less I wanted to put on the headset for the sake of playing them.

The one exception is Chronos, which draws a bit from classic Resident Evil and a bit from modern adventure games in the Dark Souls vein. It barely uses VR, with static camera angles, a third person perspective, and genre-typical exploration and difficult combat. But the atmospheric touches in Chronos are top notch. It really sells the feeling of adventuring—intruding—in this fantasy realm, being inside a world as you guide your character through it. There’s meat on the bones here, a real RPG to dig into, and that’s definitely part of what the other Oculus launch games are missing. A story to latch onto, a set of skills to keep improving, a world to explore.

Those games will presumably come, but they aren’t here yet.

Form and function

I can’t praise the strap design of the Oculus Rift headset enough. The semi-rigid rubber strap wraps around the back of my head and cradles my skull closely enough to balance the weight of the headset, giving it a vital leg up on gravity. The Rift weighs 470 grams, but a good chunk of that number is in the rigid plastic arms and the built-in earphones. That weight actually helps support the front part of the headset and also makes it surprisingly easy to put on and take off.

We ran the Rift on the LPC Jr., a system with an Intel i7-4770K CPU and Nvidia Titan Black GPU. If you need to know if your own rig can handle VR, we can help.

We tested 15 graphics cards to vet their VR performance.

We also built budget and high-performance systems for VR and confirmed we could run the Rift on a system that cost less than $1000.

Leading up to this final hardware, I was worried that putting on and focusing a VR headset would be a fiddly process every single time. Thanks to a ton of smart engineering invested in the Oculus Rift, I’m glad to be proven wrong. The front ends of the rubber strap slide into the arms at the front of the Rift, and are easily adjustable back and forth to conform to the size of your head. They help keep the headset tight against my face, and also make it fairly easy to adjust the headset for someone else’s head, often without even needing to reset the velcro straps that determine how far back the strap can slide.

The top strap is another easy velcro adjustment—while the Vive’s cable is laid on top of its velcro strap, making it difficult to adjust, the Rift’s cable snakes out its left side and stays neatly out of the way. And the earpiece arms are far better than I ever expected. Unless your ears are in a very strange place, the earphones should fit at the perfect location and angle to cover your ears.

After wearing the Rift for a week, I’ve become more impressed with how easy it is to wear and focus, and that convenience is vital for VR. The barrier to entry should ideally be as close as possible to turning on a monitor. I became familiar with the small rotations I needed to make to the angle of the headset to focus. A simple software tool built into Oculus Home shows you how to adjust the headset’s angle and its small interpupillary distance slider to fit your eyes. It’s a 10 second confirmation that the screen is in sharp focus. Unfortunately, even in sharp focus the screen has its issues with clarity—more on that in a bit.

The one disappointing flaw in the Rift’s design is the padded face rest, which is designed to be one-size-fits-all and made from surprisingly firm material. The Vive’s foam is softer and more comfortable, though I can’t say how it will hold up over time. The Rift’s firmer foam may hold its shape for a year of hard use, while the Vive’s compresses after just a few months. Maybe not. Right now, the Vive’s face rest is like one of those deep, fluffy sofas you sink into on the showroom floor. Yeah, you could get one of the firmer leather models, but this one just feels so good.

The Rift’s face rest isn’t uncomfortable, but it does leave an unsightly ring around your face after a few minutes of wear. Rounded edges or a softer foam in general would’ve really helped here. Oculus did such a fabulous job with the general weight and fit of the headset, it’s a little perplexing that it doesn’t feel a bit better on my face.

Unlike the Vive, the Rift ships with only one face rest. For me, this means a substantial amount of light leakage around the nosepiece, because it’s designed to accommodate noses and faces of various shapes and sizes. When I’m dogfighting in EVE, the light shining in vanishes from my mind. And when I’m trying to check a text message on my phone or figure out where I put the Xbox One controller, it’s nice to be able to see a sliver of the world underneath the headset. Other times I find it distracting, and I miss the rubber gasket around the Vive’s nosepiece that almost completely seals in the light.

More critically, there’s no mechanism to adjust the (depth) positioning of the Rift’s lenses, which can be a problem for glasses wearers. This doesn’t affect me personally, but two members of our staff who wear glasses expressed difficulty or discomfort wearing them with the Rift. The Vive is the bigger, heavier headset, but this kind of flexibility (and its included second face rest for narrower faces) will make a big difference for some people. Contact lenses in the Rift it is, I guess.

The display

The Oculus Rift envelops your eyes with a pair of 1080x1200 OLED displays, which are bright and pixel dense enough to avoid the distracting “screen door effect” of lower-res displays. The gaps between pixels are still there, still noticeable, but easy to look past in the heat of the moment. The OLEDs run at 90Hz, a fast enough refresh rate to mostly eliminate the problem of motion sickness for me (many other factors affect motion sickness, but a high refresh rate is a vital one). The flat displays become three dimensional thanks to a pair of hybrid fresnel lenses (you may recognize fresnel lenses by their concentric rings) designed to minimize image distortion while enlarging the displays and projecting them in a wide, curved FOV around your eyes.

The display and lens system is a great step up from the Oculus prototypes. Text was almost impossible to read on the older screens. Now it’s legible. Individual pixels are still visible, but the resolution is good enough to sustain detailed games. The cute racer BlazeRush, for example, has you driving small cars around an isometric track, snatching up Mario Kart-esque power-ups as your cars careen into one another. Even fairly zoomed out, it’s easy to tell what those power-ups are and make out the details of the cars. After years of using Oculus’s prototypes, I was initially enamored with the Rift’s final screen tech.

That faded after a few days. The more I used the Rift, playing multiple games and bouncing in and out of the Oculus Home software, the more I become frustrated with the problems and limitations of its visual system. Its vertical FOV feels smaller than the Vive’s, which is disappointing, but a limitation I forget easily in the heat of the action, when a game really draws me in. There are much more significant problems.

The edges of bright in-game objects (and especially text) produce a distracting shimmering effect some people are calling ‘god rays’ or ‘light rays.’ Imagine looking up at the sun while standing underneath a tree, and seeing bright beams of light striking your eyes from around the edges of the leaves and branches. It’s a bit like that in VR, but every bit of white text you look at will have those shimmering rays streaking out toward your eyes. They move as you move your head and your perspective on the virtual world shifts, making anything bright you aren’t looking directly at blurry.

You can see a good example of the light ray effect in action here. I don’t think I even noticed this effect at first. I was just wowed by being in VR. VR is really cool! But now I find the light rays a constant distraction, a reminder that I am looking at a screen, and often a source of eye strain when trying to read shimmery text. It’s bad in the Oculus Home software, where you need to read text, and it’s bad in games, where you want to be able to see everything in your periphery in focus.

This is currently virtual reality’s biggest failure in replicating how we look at the real world. I say virtual reality, and not just the Rift, because the same effect is present on the HTC Vive. Perhaps this is the best we can do right now at consumer prices. But after the novelty wears off, the experience of using the Oculus Rift in 2016 is moments of brilliance surrounded by consistent blur.

Wrapping up

The Oculus Rift is both a headset and a platform for playing games in a new way—hardware, software, and experience, all rolled into one. Compared to Oculus’ prototypes, the Rift is a triumph of engineering, light and comfortable with better optics than I thought would be possible two years ago. But the screen and lens technology still stand in the way of fully buying into these new virtual worlds, and that will be the case for the lifetime of this piece of hardware.

The shortage of compelling games is, hopefully, a more short-term problem. The pool of options is wide, but shallow, and for now, the experience of using the Rift without motion-tracked Touch controllers (coming separately later this year) disappoints.

I still believe in VR. I believe it will let us do amazing things. It will change the world—virtual tourism and classrooms will make the world a smaller place, social networks will become more and more like The Street from Snow Crash, and cybersex is going to get real weird.

VR right now feels less like a revolution and more like the status quo of gaming, but in pretty cool 3D.

I also believe that in this first wave, right now, most of what we can do on the Oculus Rift is not far removed from what we can do on a screen. The immersion of VR enhances experiences like EVE Valkyrie and Lucky’s Tale, but their design offers little new we haven’t seen before. We just haven’t seen it in this way before, and that’s only novel for so long. VR right now feels less like a revolution and more like the status quo of gaming, but in pretty cool 3D.

Oculus’s Touch controllers may well be the revolutionary spark I’m waiting for. When every owner of a VR headset has a pair of motion-tracked controllers, be they Oculus or Vive, someone’s going to have to toss out the old rules of game and interface design and write a new one. But the headset alone has plenty of potential untapped by the Rift’s launch experiences. Our software has a ways to go before it catches up with what the hardware lets us do.

We live in a world of multitasking and infinite options for our attention. You could argue that getting away from all that is a good thing, but in between matches of Valkyrie or while waiting for a game to load, I wished I could easily send a text, check twitter, browse the web. I can’t do that. And I can’t watch a video while I’m playing a game, or reference a guide. Until more VR games truly make use of the medium’s potential, putting on a VR headset will always start with this question: is this experience worth being completely focused on this one single activity? Is it worth the weight on my face and neck?

For now, after spending many hours with the launch games of the Oculus Rift, my answer is often no. I have faith that will eventually change. When that day comes, I’ll be one of the first to dive back into the Rift.

The promise of VR is thrilling, but the experiences the Rift enables right now are just scratching the surface.

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).