Our Verdict

With bad A.I., design issues, and repetitive combat, what there is to enjoy in Hatred quickly fades to black.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? An isometric twin-stick shooter in which you shoot civilians and battle cops.

Reviewed on: Intel i7 x980 3.33 GHz, 9 GB RAM, Nvidia GeForce GTX 960

Play it on: Intel i5 2.6Ghz, 4GB RAM, Nvidia 460/AMD HD5850

Copy Protection: Steam

Price: $20 / £15

Release date: Out now

Multiplayer: No

Link: Steam store page

Developer/Publisher: Destructive Creations

Multiplayer: No

ESRB: AO

I've done horrible and horrifying things to thousands of innocent virtual people in games, beginning with squishing friendlies in 1982's Choplifter, progressing to murdering farmers in their beds in Oblivion, and most recently by sending scores of pedestrians ragdolling through the air with my speeding car in Grand Theft Auto 5. At times I've enjoyed the violent acts I've committed against bystanders, at other times my own actions have troubled me, and there have been plenty of occasions where I've never given them a second thought. Killing bystanders in games, for whatever the reason—accidentally, purposefully, out of boredom or morbid curiosity—is nothing new to gaming.

Hatred, an isometric twin-stick shooter from Polish developer Destructive Creations, doesn't just include the killing of innocent bystanders, but features it as its primary activity. The unnamed character you control explains that he's sick of the world and the people in it, and would like to kill as many people as he can before dying violently himself. After gathering weapons he stalks through residential neighborhoods, busy town centers, a moving passenger train, an army base, and ultimately a nuclear power plant, gunning down everyone he sees to make his dark vision a reality.

How does it feel having killed a couple thousand of innocent people in Hatred? As I said, killing bystanders in a game can result in a number of different reactions and feelings. It can be a mild feeling of guilt, such as when I crowbar a friendly Barney to death in Half-Life because I want to take his ammo clip with me. It's often fun and humorous, like when visiting over-the-top destruction on entire city blocks in the Saints Row series. Killing innocents can be a means to an end or a solution to a problem, as in the Hitman games when I kill a janitor for his uniform, and it can provide a sense of grim satisfaction when I'm roleplaying a ruthless assassin in a Bethesda RPG. Sometimes the feeling is hard to define, a sort of sickening and fascinating revulsion with myself—why am I doing this?—such as when watching a character in The Sims slowly die from starvation while sitting in a puddle of his own filth because I've trapped him in a room for reasons I can't entirely explain.

In Hatred, I didn't feel any of that, and I suspect much of the reason why has to do with the quality of the game itself.

None more black

For a game that's mostly about running and shooting, there are a few problems with both. The shooting occasionally feels off: putting the crosshairs on a target usually means the bullets will hit them, but from time to time I found that aiming slightly next to them was required for a hit. Other times, at nearly point blank range, I'd fire repeatedly at someone and somehow hit absolutely nothing, even with a shotgun. Then again, sometimes I'd shoot on the run and easily take down multiple targets. The ultimate feeling is one of inconsistency, and the end result is a lot of wasted rounds shooting at someone who somehow doesn't get hit.

Having to keep an eye on the minimap to pinpoint threats, and many of those threats shooting at me from offscreen, meant I often lost track of my character, who would wind up stuck on the corners of buildings, doors, foliage, and other objects. The environment can be confusing: some hedges you can run straight through while other, smaller shrubs sometimes stop you short. Jumping over objects is possible, performed automatically while sprinting, though it's inconsistent as well: some obstacles don't allow you to vault them when they appear they should.

This clumsy navigation is exacerbated by Hatred's visuals. It's presented in mostly black and white—things like explosions and explosive items, taillights and security locks, and some set dressing like billboards and banners provide bright splashes of color. I think this is a neat idea, and I do really like the look of the world, but limiting the game to black and white requires a real mastery of design that's unfortunately absent here. Smoothly moving a small character clad in black on a black night through a black forest while spotting enemies (they're dark gray, at least) isn't an easy feat to manage.

Your character is not some superman capable of absorbing massive amounts of damage. Slow, deliberate assaults against the police and later the army are required, as are frequent retreats. This is initially more interesting than charging mindlessly into combat, and I did find early fights with armed forces fun. Eventually, though, forced to progress inch-by-inch through the maps while frequently falling back to regroup or lose pursuers, the game becomes a slow and repetitive trudge, since progress is almost always based on killing a specific number of targets as opposed to reaching a destination. The only change as you progress is more enemies that take more shots to put down instead of any real evolution of gameplay, and the handful of different guns you can use don't add much variety. While there are a few optional objectives on each map, they're almost always the same: kill X amount of people in a certain location, and most levels end with similar standoffs against swarms of law enforcement. There's also driving, for which the controls are comically bad, though thankfully it's only briefly required in a couple of missions.

Poor execution

The only way to heal your wounds is by performing an 'execution', in which you stand near a wounded victim and press the Q key to finish them off. This results in an animation in which you stab the victim in the head, cut their throat, stomp their head into mush, or bonk them with the butt of your gun. While I appreciate that the developers went looking for a different way to heal besides collecting health kits or auto-healing while at rest, the execution system is pretty terrible in all respects. Since you're unable to deliberately wound people (in a third- or first-person shooter you might be able to target limbs, for example) it means that trying to restore health can result in long, dull stretches of running around, shooting stragglers, and simply hoping to wound someone rather than kill them outright. Ultimately, this turns out to be even more of a hassle than hunting for health kits and takes longer than auto-healing would.

The executions themselves, both for the gore-factor and from an animation standpoint, are rather underwhelming, with fakey looking blood and unconvincing character movements, and within a few minutes of play you'll have seen most of the handful of animations. Whatever effect executions are supposed to have on the player (glee? revulsion?) will wear off long before you've even completed the first level.

It's not all bad news. The environments themselves are great: big, sprawling maps to romp through, nicely designed buildings, some great set dressing, and a convincing level of detail. The destructive environments are fantastic. Gunfire will leave walls crumbling and windows shattered, grenades can create new entrances or exits in most structures, big and satisfying explosions routinely light up the screen. A protracted confrontation in a building results in the structure becoming a gutted, flaming mess and leaves you feeling like a badass for stalking out of the smoldering ruins in one piece.

I enjoyed the second level, in which you must navigate through a sewer system while SWAT teams slip down ladders for periodic confrontations. I felt this, and a trip through a nuclear plant at the end, were a nice change because they were a bit more linear, giving me a real direction to travel, giving me chances to plan my approach and crouch behind cover when enemies advanced. I felt like I was fighting my way through something, as opposed to the vague, free-form assaults the open maps provide.

Not all citizens in Hatred are helpless targets. Some have guns of their own, others will pick up guns dropped in the street and fire back. This idea of the danger of armed bystanders culminates in a level where an optional objective is to kill everyone at a gun show, and I laughed when I ran in the door and saw a dozen people promptly grab weapons off tables and pump me full of lead. Ironically, I suppose, for a game built around massacring innocents, it's far more fun when they fight back and you're not simply offing pedestrians until you meet your quota. Seeing a woman in a grocery store pick up a gun, empty a clip at me, and shout "reloading!" as if she were part of a trained commando squad was funny, and any time a citizen did something other than slowly and ineptly flee my gunshots was a welcome change.

Brain dead

No matter who is holding a gun, however, Hatred's A.I. is underwhelming and at times entirely broken. On one map, after slaughtering a house full of people, I hit my murder quota and was told a SWAT team was arriving: I'd have to survive the raid and kill 20 cops to progress. I hunkered down in a bedroom on the second floor of the house and waited for them to swarm up the stairs, hoping to pick them off one at a time. As it turns out, only one cop was actually trained in the delicate art of using the stairs. The rest milled around on the first floor for long minutes while I waited, apparently able to see me through the floor but not actually able to shoot me through it. More and more cops poured into the lower level of the house until it was a teeming mob of idiots getting caught in their own crossfire. I eventually passed the mission due to 19 separate friendly-fire incidents because no one taught the police to climb stairs and not to aim through each other's bodies.

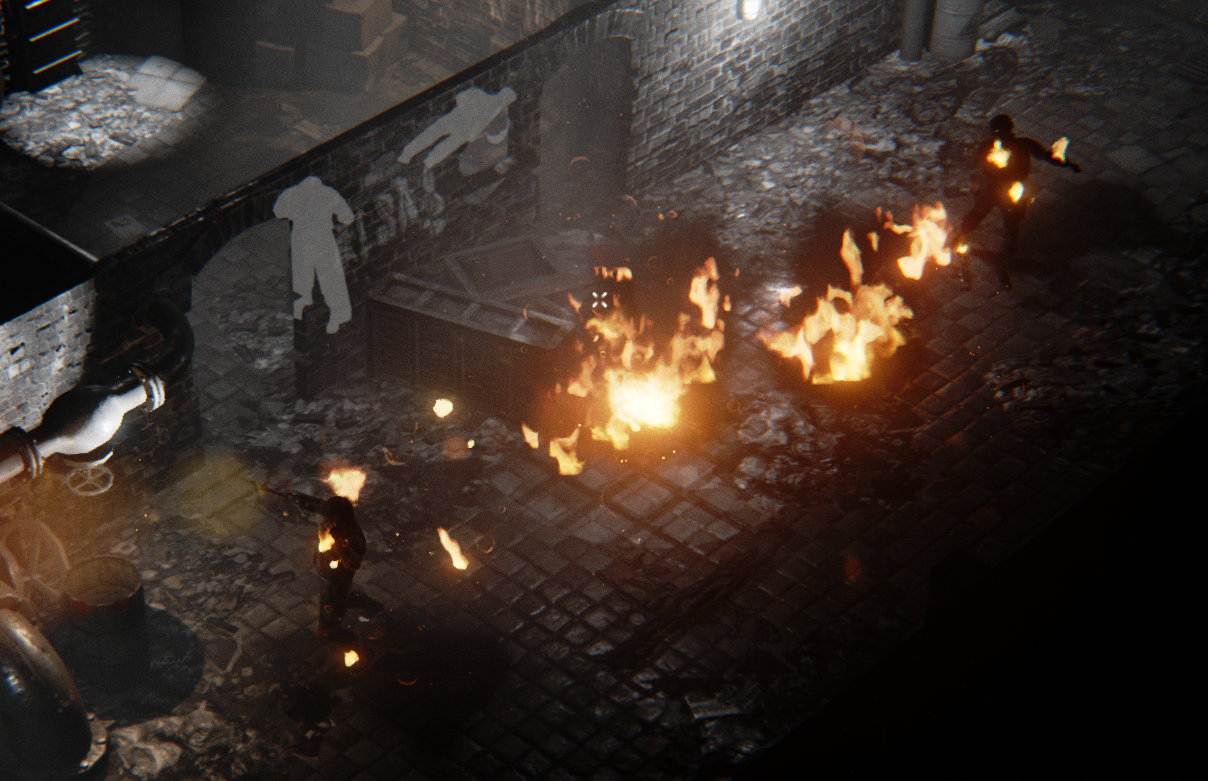

On another map I had to personally destroy the walls of a bank with grenades to allow the police to move through the building toward me, just so I could then kill them. Molotov cocktails, meanwhile, become useful when you realize the lake of fire they create doesn't register as a threat to police, who will voluntarily wade in and out of it until they've burned themselves to a crisp. I actually stopped playing at one point to check if Hatred was in Early Access instead of full release, because it genuinely feels like a beta.

While the idea of massacring innocents in a game will turn of plenty of people off and genuinely upset some, I found nothing about the experience daring, novel, or even particularly shocking. Maybe it's that the people are so poorly simulated, maybe it's that the execution animations are so unconvincing, maybe it's that the game just isn't very good. Last year, the developers said they created Hatred in response to the trend of political correctness in games, but if that was their true mission statement I'm afraid I don't see it reflected in the semi-finished product. Much more likely, this statement simply represented the marketing plan to promote their substandard shooter (and it's hard to argue that plan wasn't a successful one). Ultimately, in Hatred, killing innocent people is just a way to make the cops arrive, and I can do that—plus dozens of other, actually fun things—in a game like GTA 5.

There are a few things I enjoyed about Hatred, but its many and major flaws quickly turned it into a largely forgettable shooter that grew less and less interesting the longer I played. For those hoping for a game in which killing innocent people provides you with some sort of entertainment—be it humor, revulsion, guilt, a vicarious and morbid thrill—you can find it done better, in one way or another, in every other game I've mentioned in this review.

Set a fire, hide behind a wall, and watch the po-po walk around until they burn to death.

Crosshair on guy sitting? Check. Fired shotgun? Check. Wall behind guy hit with shot? Check. Guy completely unharmed? Check.

Can't find the door? No problem.

Not this many lab geeks have died since the Black Mesa incident.

Please eat at Restaurant, the restaurant you have to walk inside of to see the sign that tells you it's a restaurant.

With bad A.I., design issues, and repetitive combat, what there is to enjoy in Hatred quickly fades to black.

Chris started playing PC games in the 1980s, started writing about them in the early 2000s, and (finally) started getting paid to write about them in the late 2000s. Following a few years as a regular freelancer, PC Gamer hired him in 2014, probably so he'd stop emailing them asking for more work. Chris has a love-hate relationship with survival games and an unhealthy fascination with the inner lives of NPCs. He's also a fan of offbeat simulation games, mods, and ignoring storylines in RPGs so he can make up his own.