The making of Gone Home

There is a strong feeling of place in The Fullbright Company's Gone Home. A critically-lauded first person exploration game about a house and its inhabitants, Gone Home tells a powerful, moving story about two sisters' lives through the artifacts of the everyday. The tapes left lying around the house are tracks from Riot Grrrl bands, the sort that grew out of Portland, Oregon in the 90s. Letters and postcards addressed to the house litter every surface. Like its spiritual parent the Bioshock series, the environment is the fabric of the story itself. The relationships the family have with each other, their neighbours, their childhood friends, their longings fall into relief as you traverse this home. There's no doubt in your mind once you finish the game that this house contained real people who liked each other, got on with each other, were a family.

"We worked together before and we made something we were proud of before."

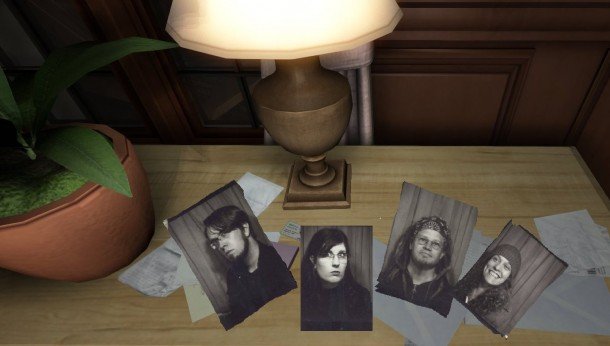

The Fullbright Company - Steve Gaynor, Karla Zimonja, Johnnemann Nordhagen and Kate Craig - live in a house together in Portland, Oregon. This is where Gone Home was made. This is a retrospective look at the collaborative aspects of how Gone Home was produced, and how pragmatic game design and projects of a strict scope can be more of an expression of who the creators are. Go and play the excellent Gone Home now, if you haven't already, for what proceeds are a few small spoilers.

The co-founders of The Fullbright Company gained their development expertise working on big projects like Bioshock 2 and the Minerva's Den expansion and wanted a project of their own. The first step was to find a space for that to happen in. “The reason we are in Portland is because I used to live here,” Steve says. “I went to college here and my wife is from here, so my wife and I had decided to be here already. We were going to be here. At the very least, Karla and Johnnemann knew that I was already here. We had a base of operations. The first place we started working together was in my wife's parents' house while they were out of town while we looked for our own place.”

“We worked together before and we made something we were proud of before, and the fact that I set up a base camp before people moved up here to meet up with me, at least there was a little bit of solidarity."

Throughout Gone Home there is a strong feeling of not only place, but transience. The feeling of the recently uprooted. You play as Kaitlin Greenbriar, the eldest daughter who has just returned to her family's new house from wandering Europe. From the address on the Wellspring Movers invoice found in the lobby, you can look up the zip code of where in Oregon the fictional house is situated. It's a Tillamook zip code: OR 97141. A little adventure in Google Maps shows you that Tillamook is green, tree-laden landscape that reminds me of a flatter Scotland. Tillamook is mostly populated with dairy farms. It is a place that has a removed quality about it. It looks peaceful.

"By the time we hit the ground we were ready to start putting stuff on the screen."

One can imagine that this is a sense of transience that was felt in the Gone Home studio. Everyone left to work on this intense project, and now they have finished they are moving again. “We will get paid soon." Steve says. "The biggest reason we all split a house was that we are living off our savings, it's a big reason we're in Portland, the production constraint for this project was how long could we live on the money that we have. We all split rent to keep costs low.”

The move is indicative of the team's pragmatic approach to production. Gone Home was created in just a year and a half of disciplined development, controlled by a keen awareness of the team's limits. “The big thing was the biggest parameter of what kind of game we could make, knowing who we had and what we were good at was a prerequisite," says Steve. "So we started coming up with specifics between the point where we had left all our old jobs. Karla and Johnnemann moved up here, we were actually on site ready to start producing stuff. By the time we hit the ground we were ready to start putting stuff on the screen.”

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Each character in the Gone Home house has their own individual story strand: Samantha embarks on a teenage romance, a budding fiction writer; Terry, the father, is in a sort of mid-life crisis, struggling with his publisher to have his latest book published; the mother is meditating quite clearly on having an affair. The boy next door even figures, someone who you sense is not just after Nintendo games. Each member of the family, even Kaitlin, contributes an important foundation to Gone Home's narrative.

I ask Karla and Steve if putting together the pillars of the Gone Home team was like putting together the A Team. “ It definitely was,” Steve says, matter-of-factly. “Some people may say A Team, some people may say like a band I guess.”

“Or like Voltron,” Karla says.

“Karla is really good at being our right leg if we're going with the Voltron thing,” Steve agrees. “But it depends on what metaphor we're working with. It is very much like at [2K] Marin, one person was responsible for each specific discipline. It was like programmer, 2D artist, 3D artist, and writer/designer. You know, all those aspects overlapped, and as far as we were giving input to each other and kicking ideas about what each other was working on, but at the end of the day… yes all the 2D art in the game was from Karla, and all the 3D models in the game will be from Kate with a rare exception.

“I touched the very tiniest bit of Johnnemann's code once or twice or something,” Steve adds, “but for all intents and purposes he programmed every single thing in the game that didn't come with the unity engine. So yeah I think it is really nice actually to be 'I own this one great elemental part of the game, and be totally responsible for it."

This approach produced an extremely streamlined game that didn't do more than it had to, or fall short of anything. Each person in the team had experience in exploratory storytelling, so they knew that was the kind of game they were best at making together.