Crapshoot: Sanitarium, the amnesiac horror classic

We're rerunning Richard Cobbett's classic Crapshoot column, in which he rolled the dice and took a chance on obscure games—both good and bad.

From 2010 to 2014 Richard Cobbett wrote Crapshoot, a column about rolling the dice to bring random obscure games back into the light. This week, it's the lighter side of amnesia as... oh, no, wait. Sorry. Forgot where I was for a second. What a conveniently uncontrived coincidence!

It may be Horror Cliche #7, but as games like Planescape: Torment, Amnesia, and... possibly some others have demonstrated, a game that starts with memory loss doesn't have to be a creativity vacuum. Case in point, Sanitarium, which took this most tired of tropes and did enough with it to be declared an instant cult adventure favourite when it landed back in 1998. Is it a great game? Much as I'd love to say yes, honestly, no, not really. It's one I like though, and definitely unique.

Be warned, spoilers ahead—to be exact, pretty much all of the spoilers.

Sanitarium is the story of a man named Max, who doesn't know his name is Max, but who is named Max. Like I said, all the spoilers! This is your last chance to bail out! There will be no more warnings!

Being the star of a psychological horror game whose box art can win any staring contest known to man, Max is in a bit of a pickle. All he remembers is that he's been in a car crash, from which he wakes to find himself in what looks like a grim medieval tower, his head completely encased in bandages, and his pounding headache not helped by the sound of fire alarms and human misery. A few metres away, a crazy inmate is bashing his head into wall-jam. Just round the corner, another leaps to his death with pants round his ankles. Grim. Psychologically horrific, even. But is this real life? Is this just fantasy? Caught in a bad spot, has Max escaped from reality?

Ahem.

Like a lot of these games, Sanitarium sets up a wonderfully creepy, mysterious opening that honestly its main story can't live up to. On the one hand, yes, much of it feels symbolic and allegorical—but when you actually look at the whole sweep, it's not necessarily symbolic or allegorical of anything much. A lot of it is, don't get me wrong, and there's a lot of clever detail on offer—like the way the stained glass windows and conversations in the very first area foreshadow most of what you'll ultimately see—but Sanitarium isn't afraid to be weird for the sake of... well... simply being a bit weird. There's not a lot of actual steak underneath the huge pile of seasonings that give this meal its interesting taste.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Max himself is probably the biggest missed opportunity. This is a YMMV level writing thing, admittedly, but you know how your average tormented horror 'hero' is usually weighed down with dark secrets or crippling personality issues or similar—something awful like being a murderer subconsciously seeking punishment and such? Well, that's not really the case here. Instead, our Max is... a doctor who's devoted his life to childrens' medicine. He's happily married. No dark past at all. Hmmm.

Why's he in the world's worst hospital? Well, ignoring that he clearly isn't—it's all a dream—it's because he invented a cure to a major disease, which would harm his boss's profits. His boss cuts his car's brakes. He's now in a coma. And that's essentially it. It sucks to be him, sure, but it's not actually that interesting to be him, given the internal nature of the struggle he's on for the entire game.

The game itself also doesn't always play fair with its mystery. At the very start, for instance, the absence of guards or doctors is explained by a fire, with the inmates simply being left behind. Alone, that would be fine. Max specifically gets called out though as "That's the bastard who stole my car!" to cast some doubt on the intro where we see him crash. Seriously. They don't make bigger red herrings than—

Oh. Hmm. OK. Never mind then.

So, if the story's a little wooly, why do people like Sanitarium so much? Firstly, with this kind of game, you don't actually know it's a little wooly until the reveals, and by that point you've had the time to be wooed by its other charms. Secondly, and more positively, it's a wonderfully imaginative and atmospheric game. Only alternate chapters (give or take) are actually set in the stone halls of the sanitarium itself, with Max spending the others Inception-ing his way into other layers of the fantasy—a circus from his childhood, an alien hive, an Aztec-themed world, and finally a mix of all them as he races to escape from his own mind. In each, he plays someone different—gruff, arrogant Olmec amongst the Aztecs, his favourite childhood superhero Grimwall against the aliens, and most memorably, his little sister Sarah to explore the circus that really puts the 'fun' into 'coulrophobia'.

Wait, did I say his little sister Sarah? Sorry. I meant of course his dead little sister Sarah. How a small word like that can completely alter a game's tone, even if she's pretty cheerful throughout.

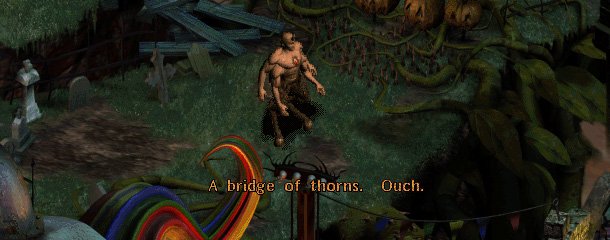

It's these memories that stick in the mind the most, and where Sanitarium hits its early highs. The journey starts in the second chapter, in a village of abandoned, deformed children left to fend for themselves—a boy with two mouths, a girl skipping on two wooden legs, another who looks like a ghoul. It's only by talking to several of them and having sepia-toned flashbacks that Max remembers his own name—and a day as a child when his mother came to see him and carefully told him that "Sarah would like to see you now." Ominous... possibly even to the point of Boding.

And speaking of ominous, where are the the adults in this village of the damned? According to the children, "Mother" won't let them talk about that, "Mother" says all adults but her are bad, and "Mother" seems to have a thing for mutilating kids and throwing anyone who complain into the pumpkin patch. So yeah. It's a fairly creepy chapter, even if it does make you play a game of Tic-Tac-Toe at one point. Like playing with a cute kitten, nothing's as creepy after a few minutes of casual Tic-Tac-Toe.

Now, the Towers of Hanoi? Those are some scary bastards. Brr!

The creepiness factor only rises as you explore the town and slowly pick away at its backstory—talk of child abuse and how everyone just excused and turned a blind eye to it, of deaths and unspoken horrors that are admittedly a little undercut by the reveal that Mother is a glowing green meteorite/plant monster, but still pretty effective.

These were not the kind of topics that even adult PC games typically covered in the 90s, and indeed, still pretty much don't outside of games with the words "Silent Hill" in the name. Mixed with not knowing what part, if any, all of this played in the wider story—or indeed, what the wider story even was—this first chapter made for a phenomenal introduction to Sanitarium's style.

(Admittedly, it does suggest that all the world's social problems can be solved by rigging the right battery up to some alien's genitals. But who knows? Maybe that will indeed be a Lesson for the Ages.)

Following a quick trip back to the Sanitarium to mend a fountain for reasons that are possibly meant to be allegorical, but mostly seem to symbolise adventure game designers' love of silly logic puzzles, comes by far the best chapter of the game—and the one that made Sanitarium a cult classic.

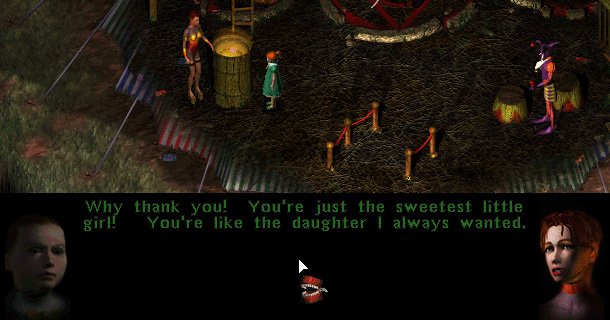

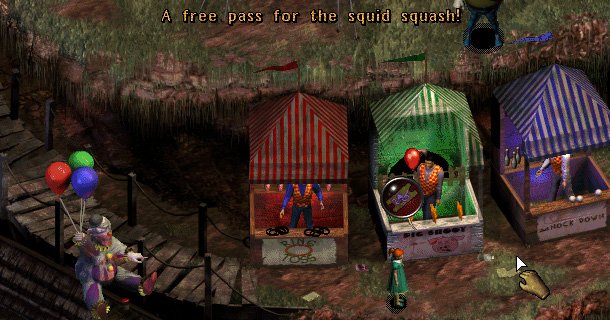

It starts off in a spooky circus, with a confused Max physically turning into his little sister—herself awaking with nothing in her pockets and her own mini case of amnesia. The circus owner, Baldini, gives her a pass to the Test Of Strength game (though this being Sanitarium it's actually an octopus you hit to squirt ink as high as you can) to win tickets. The weirdness then continues as you poke around, try to work out which of the creepy carnival folk are actually malicious, persuade a strongman to show his devotion to the fire-breather Inferno (Max's wife in reality) by tattooing her name on his skin, and memorably describe rubbing alcohol as "smelling like clown breath."

I really don't want to know how Max's fevered mind knows this particular titbit.

Especially when the clown of his dreams/nightmares turns out to be called "Spanky."

And you realise that there is in fact no 'fun' in 'coulrophobia'.

As with before, everyone's trapped by a monster—in this case, a giant squid. Sarah/Max gets past this with the help of fire breathing lessons... don't ask... and turns its monstrous core into calamari. I didn't mention the fighting bits earlier, because they're awful. This is no exception. However, they're blessedly quick, and once it's done, little Sarah finds herself standing in an oddly familiar mansion.

And then comes what I think most Sanitarium players would describe as "That Bit".

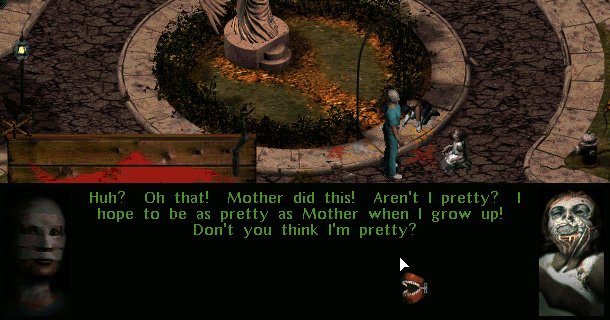

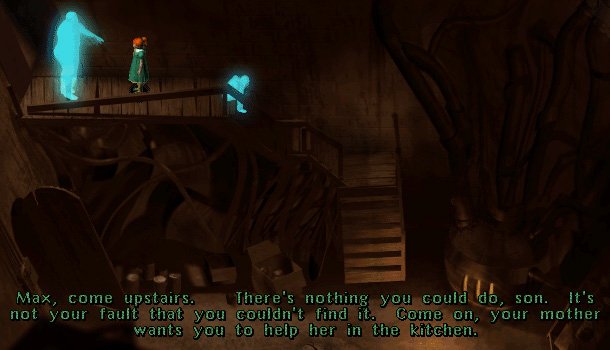

What's the level? It's Max's house, sepia-toned and shaky, and his greatest regret played out in reverse. As mentioned, Sarah is long dead—she died as a child, and it's revealed that the circus level is a twisted mix of Max's current nightmare and her longing to visit the circus despite being bedridden with a mysterious disease.

It goes deeper than that though, with Max's biggest regret revealed to be a deeply human one—that his sister asked him for her favourite toy and he failed to get it in time. It's a small thing... probably something nobody but him even remembers. But then, these things often are.

It's easily the most touching part of the game, though like a lot of emotional game bits, not something you really get by simply watching it on YouTube—the time spent with the characters, the immersion in the world and the story, and the general sense of unease from both the darkness up to this point and its sudden contrast all play as much of a role as the actual writing, and help to mitigate the bad acting.

This section is about Max finally coming to terms with his sister's death, but it's not played out like that—instead, it's about Sarah witnessing the miseries her death left behind. It's not overly dramatic. The family isn't collapsing in on itself as a result of the tragedy. They're simply... coping. Her father keeps torturing himself with home movies of happier times, but not to the point he doesn't recognise it. Her mother toys with a piece of clothing and muses how warm it would have kept her at the circus. Sarah herself doesn't react to any of this, but she doesn't have to. This is going on in Max's head, and for his benefit—a way for him to finally put her ghost to rest and move on.

With this in mind, it's a powerful scene, and has an excellent finale. Having found the doll, Max-as-Sarah hurries to take it to her in her bedroom, the sepia graphics blown away by a sudden rush of colour. Now, Max is the physical presence in the house and Sarah again becomes the ghost. Nothing's changed, not really. In seeing her as a ghost, he isn't pretending anything went differently. Now though, he gets to at least accept that fact and forgive himself for it. If Sarah's assurances that "You could never let me down, you're my hero!" sound a little saccharine... well, they are. But that's not the point. The key to this conversation isn't whether or not it's a realistic scrap of dialogue that a dying little girl would actually say, but what that brother still desperately wishes he could have been for her some 20 or so years later. As much pain and suffering awaits on the rest of this journey into his mind, this one moment probably makes it all worthwhile.

Except the big maze later on. That bit is just shit.

More often than not, it's moments like these that make classic games so special—not necessarily sad and sombre, but a sudden emotional connection that's all the more powerful for not being expected. Sanitarium is, supposedly, a horror game. You expect to remember something gory or horrible, or a big twist that made your mouth drop with an audible clang. Here though, it's not the nightmares that stand out, but that tiny glimmer of hope in the middle of them. It's a question of contrast as much as the actual content, but that's absolutely fine. If it works, it works. The path it takes doesn't really matter.

As for the rest of Sanitarium, it has its ups and downs—the other two fantasy worlds with a couple of interesting moments, and the central hospital location increasingly marginalised by the fact that it doesn't really go anywhere. The opening section in the dark, almost prison-like tower, remains a stunningly atmospheric opening. The later bits you explore try their best, with creepy writing and bloody scenery, but just don't have the same power. They're less personal, less connected, and just generally much less effective. Still, it's an enjoyable journey for what it is, with an enjoyably creepy villain finally showing up to have one last crack at keeping Max in his psychological hell, and a refreshingly upbeat ending for a genre that generally loves to pull the rug out from under its characters.

If you want to check Sanitarium out for yourself, GOG and Steam. Alternatively, here's the whole game in handy Longplay format via a little-known site called "YouTube", though be warned, more than most games, you really won't get the same atmosphere by just watching someone else play. And not just because of the abysmal voice acting—though goodness, that doesn't help.

One final thing. The end credits if you win the game (as opposed to the ones from the main menu) are a bit wacky, being made up of sound samples from the game that think they're much funnier than they are. I only mention this because otherwise I know someone will ask why I didn't. So, there you go. But do they beat Legacy: Dark Shadows? Please. They don't even look like a burglar to me...