Our Verdict

id hasnt strayed far from their roots, but they still know how to make a top-quality shooter. Simple, satisfying fun.

PC Gamer's got your back

I've just picked up a keycard, and I'm confused. I found it in a power station, out in Rage's wasteland. It was about a foot wide, and bright blue, and now it's in my inventory. What the hell do I do with it? Do I sell it? I swear I've done this before. Does it... does it go in this bright blue door, over here?

Swoosh. The door opens.

For all its open roads and bright blue skies, for all its sweeping canyons and hub towns, Rage is still resolutely an id Software shooter. For all their pre-release bluster of expansive worlds and template departure, no one knows this better than id Software. The keycard is as much of a nod to their previous works as the Doom mug collectibles players can sell to shopkeepers, but it also feels like an acknowledgement of a design lineage: despite the apparent differences, Rage is the continuation of the corridor.

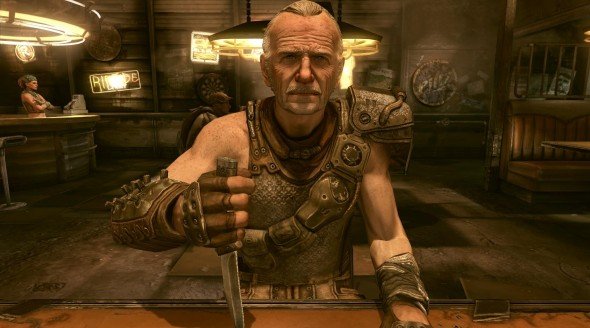

You wake from cryo-sleep as one of the world's last super-soldiers. You've been put in the freezer and sent into space due both to your perceived aptitude at rebuilding societies after mini-armageddons, and your badassitude. But – as the desiccated corpses of your chums in the tubes next to you demonstrate – something went a bit wrong. It's 106 years after the mildly explained apocalyptic Bad Thing happened, and the destroyed world has split between rival gangs of mentalist bandits, flesh-eating mutant freaks, moustache-twirlingly evil fascists, and honest folks trying to make a living. It's this latter lot with whom you throw in your hat-made-of-guns.

These folks might peddle an image of the innocent settler, but almost everyone you meet on a polite conversational basis – as opposed to those who want to make your skin into a coat – wants you to go and eradicate swathes of humanity. Rage's missions don't need much explanation: you're sent down into a pit, and once you're in there, there's no talking to the man-monsters that dwell within.

I followed tight paths through power plants, down sewers, and clifftop shanty towns. Doors are kept conspicuously shut, partly to dissuade the dream of deviation, but also so the same area can be rearranged and returned to as part of another, later mission. Missions aren't ever complicated, but they are consistently well paced and imaginative – never too short, rarely too long – and spotted with the right amount of spectacle and surprise.

Rage's post-apocalyptic wasteland regularly opens out into bowls and basins: little thunderdomes for the game's car combat. They give players space to use their vehicles' boost and handbrake, time to deploy rockets, machineguns and strange pulse weapons to immolate the bandits on their tail. But these sections aren't the norm, just thicker beads on the thread connecting the game's three hub-towns. Driving between these townships is where you work through Rage's more typical shootery bits: murder anyone who gets in your way and never stop moving forward. And there's absolutely nothing wrong with that.

There's not much to distract in the wasteland, in any case. Hub towns provide missions, each of which requires Rage's Mr Rage (not his real name, but better than his actual title of Mr Buzzcut Generosoldier) (also not his real name) to go to an allotted place and introduce bullets to the skulls of everyone who lives there. Accept a quest and you'll be given a little marker to head for. Chug around the game's outsidey bits without a quest and you'll find a true wasteland: there's little to do beyond wreck the handful of car-driving bandits who respawn every time you poke your head out of a settlement. I quickly started to reserve my jaunts outside to mission-specific journeys, only hopping in my car when the job asked me to leave town.

The jobs did that often. In a ten-hour game, I spent about an hour at the wheel, and a few more in multiplayer (the only competitive modes are vehicle battles, and two player co-op missions the only way to shoot with a friend on foot). Fortunately, Rage's vehicles are fundamentally pleasing to drive. They feel responsive, even with the binary input of a keyboard. But better than that, they feel fast.

Each comes with a boost capability. It's designed to give you the edge in races or let you outrun bandits, but I found a tertiary use for it while at the handlebars of the game's first ride. Fresh out of the Ark – the game's space-bunker equivalent of Fallout's Vaults – I was given the keys to a little quadbike runaround. It wasn't the most intimidating machine I'd drive in the game: by the end, I'd unlocked another three vehicles of increasing power. But while they let me shred enemies in a few salvos, they didn't allow me to hurtle into an immovable bollard at 100mph, launch my screaming marine 30 feet through the air, smash my spine against a wall, then flit back to consciousness next to my bike as if I'd not just reduced my skeleton to slurry.

This pulse of mischievous fun beat a little weaker in later driving sections. At the wheel of the final Monarch car, I was so overpowered in comparison with my bandit peers that battles were dull dominations.

Races – organised by the bored NPCs at each hub – provide a secondary reason to drive. They don't affect the main story directly – but success in the ranks wins you racing credits, which can be pumped into the upkeep and outfit of the car you use in the wasteland. Races fall into three types: time trial, rocket race and rocket rally. Time trials are about perfectionism, where you hit boost refill power-ups to keep yourself travelling at just sub-mach speeds. The rocket brothers are more brutal, asking players either to complete a course in first place or to pass through an ever changing series of checkpoints while three enemies pepper their car-arse with rockets. The first is too easy – just boost to get ahead on the first lap and you won't be touched. The second is often screamingly too hard.

I played Rage in a room with other people playing Rage. Once, just after passing through the final checkpoint on my fifth attempt at a rocket rally, I looked up to see someone shooting a mutant in the face. For a second, confusion flickered in my mind. What game were they playing? That moment is the greatest compliment I can pay to Rage's driving sections: although oddly divorced from the main game, the base mechanics behind car control are surprisingly solid for the work of a shooter studio.

And the shooting itself? It feels good: each weapon is blessed with a distinctive bark and kick. id have jettisoned the modern shooter's neurotic arsenal restrictions, letting players carry nine weapons around on their travels, each safely secreted on a number key. Most have two or more ammunition types, their rarity roughly concomitant with either their usefulness or ridiculousness. The functional secondary ammo for the Authority machinegun, for example, simply rips through armour faster. The pistol's third ammunition type typifies the other approach: it fires an entire eight round clip in one go, and the bullets are shaped like Pez dispensers made of human bones.

Sadly, there's some artlessly wedged-in console crossover nonsense when it comes to controlling the shooting. Creative director Tim Willits argues that Rage plays better on a pad, and so for hot-swapping between ammo and weapon types, we sensible mouse-and-keyboardnauts are lumbered with a strange setup that forces us to assign weapons to one of four slots. Ammo can still be switched by cycling, but it adds a user-unfriendly sheen to fights, and makes precise control trickier.

That control is important. The game's enemies are tricksy bastards, juking and jiving away from your ironsights. I'm used to my FPS opponents sprinting directly toward me, pointing at their foreheads and screaming “AIM HERE!” Rage's mutants and bandits duck as they close on you, hop out of bullet volleys, and use walls and railings to get the purchase necessary for an attacking leap. It's almost as if they don't want their brains emptied onto the floor, and it's both infuriating and admirable: the former for a millisecond as you waste the ammo, the latter for longer because scraps are kept fresh and tense. Only later in the game, as the enemies slather on thicker armour and keep their feet on the ground, do firefights descend into cover leapfrog.

But by that point, I wasn't doing much of my own shooting anyway. Rage comes with a crafting system, fed by a mini economy. Every surface is littered with bric-a-brac to sell or use – it's a dream game for compulsive tidiers. Recipes can be purchased for various battlefield gadgets. The humble wingstick – a razor sharp boomerang that removes heads at 20 paces – is the most useful, but I fell in love with the spiderbot. I spent the game's anticlimactic final level letting my robo-chums do my annihilation for me, stepping into fire only when I wanted to try out the BFG rounds for my chaingun. Both approaches – dirtying your hands and standing back – feel satisfying.

Rage isn't a complicated game. Despite what the developers might have suggested and we might have assumed, it's still set in a corridor. Fortunately, id still make some of the finest corridors in the world.

id hasnt strayed far from their roots, but they still know how to make a top-quality shooter. Simple, satisfying fun.