The Norwood Suite's creator on composing the game's soundtrack and standing out from the crowd

Greg Heffernan, aka Cosmo D, is a professional jazz musician-turned-game designer.

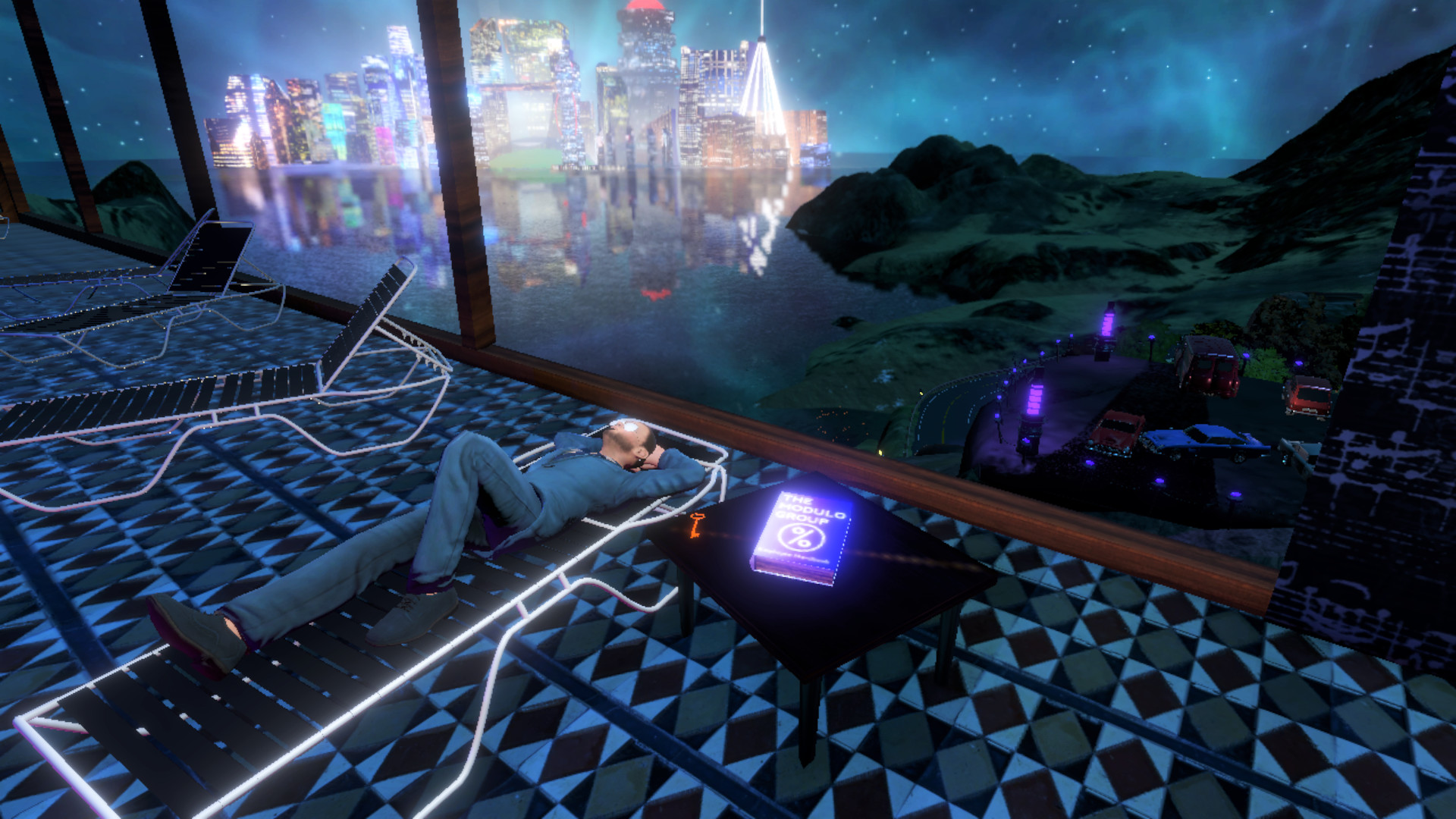

Released earlier this year, The Norwood Suite is a quirky first-person adventure game that draws from the likes of Twin Peaks, Gone Home and Dear Esther. Developed by professional jazz musician Greg Heffernan (otherwise known as Cosmo D), its soundtrack pulls on the creator's professional expertise.

Muscially, Heffernan cites Soma, the Divinity series, Fallout, Arcanum and Stalker as key sources of inspiration, and, perhaps expectedly, considers music and how it's applied crucial to the narrative process.

Following the launch of The Norwood Suite last month, I caught up with Heffernan to discuss its reception, the challenges posed by its creation, and how it plans to become an anthology series.

PC Gamer: The Norwood Suite came out at the start of October, how has it been so far?

Cosmo D: It's been cool, it's been everything I've wanted in terms of how people have taken to the game, how people have been talking about it. I knew that people might think it was weird or unusual, but I also know that people who played my last game, Off Peak, kind of know what they're in for. The response from people that I think were open-minded to that sort of aesthetic, I think it resonated with them so I'm grateful for that.

Greg Heffernan, otherwise known as Cosmo D, is a professional jazz musician-turned-videogame designer. His first game Off-Peak is a short, free and quirky venture that's since been followed by the similarly idiosyncratic The Norwood Suite. Cosmo D composed both soundtracks, both of which are central to each game's narrative.

Your games are, you could say, weird. But this is what makes them special. How do you deal with those people who aren't as open-minded, as you put it?

Well, people have been calling me weird all my life, since I was seven years old on the bus. It's not a thing that I'm a stranger to, and my response is basically: Take it or leave it. If you want to dive in, it's there for you, but if it is weird, like, off-puttingly weird, then so be it. I never make my games to be intentionally weird or weird for weird's sake—I try to make my games true to who I am and true to what my sensibilities are. I feel like I'm comfortable enough in my own skin to know that some people will thrive on it and others might not.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are, first and foremost, a musician. Tell me about your relationship with videogames—have you always played them?

I'm a lifelong gamer. My parents wouldn't like me have a console after the Nintendo, they were like: Okay, you're playing too much Nintendo, but they did get me a computer. The first games they got me were Kings Quest 5 and Ultima 6. So I got that early PC gaming thing deep in me. And that carried through the '90s, through my childhood, through my adolescence, the immersive sim wave of the '00s hit me pretty hard, but I've loved all manners of the PC gaming culture.

That's where I'm coming from with this, and although I'm a musician and have been a musician professionally, teaching myself how to use game software later on made me want to reach the ethos of those games, maybe not the complexity of the ones I loved, but at least the sense of freedom and mood and experimentation.

Was that what inspired you to get into game development—the games you played when you were younger?

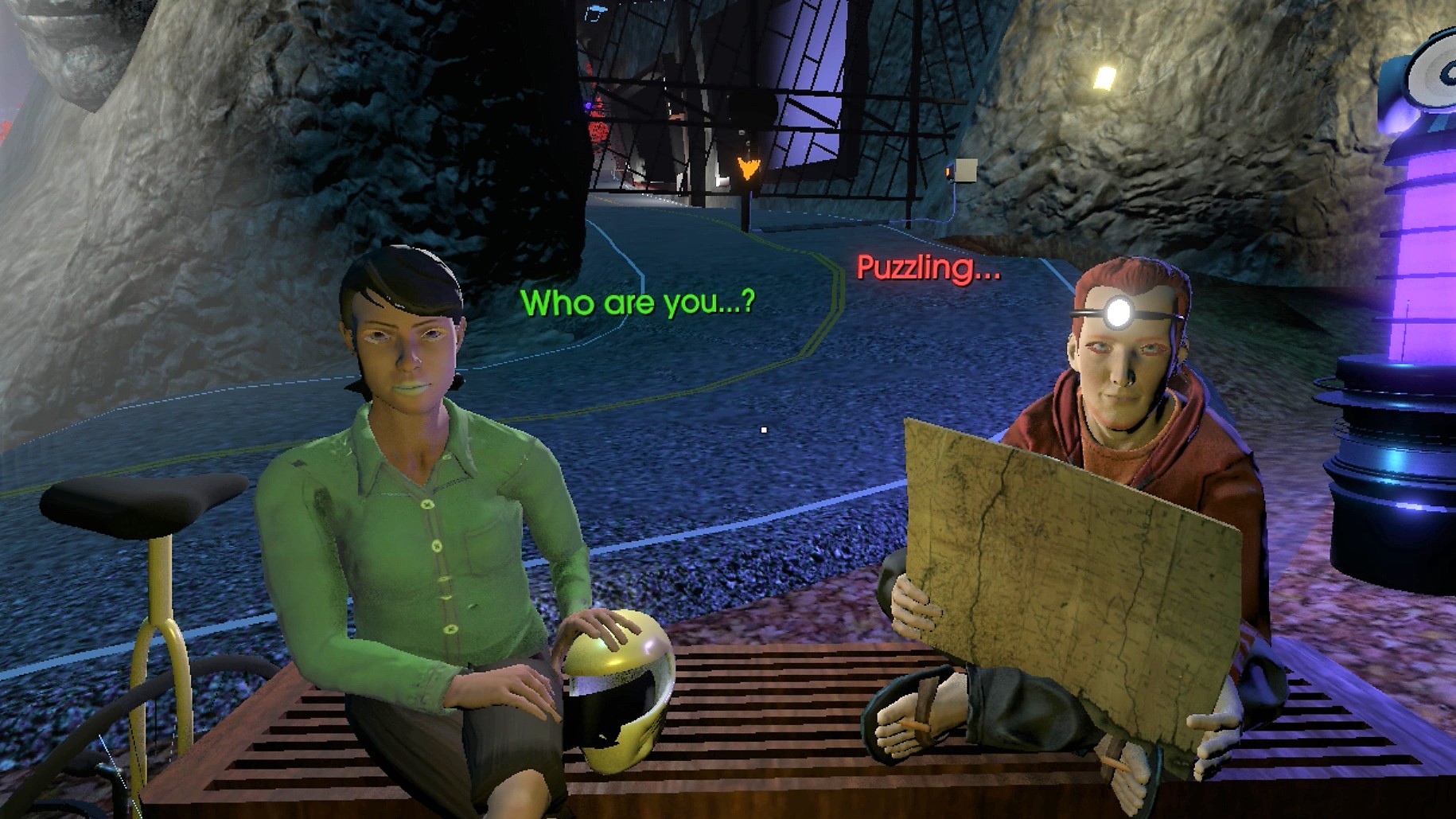

Totally. The games that I played when I was younger and the games that I played that I think have had the biggest impact on me in various times of my life. Also, just combining that general sense of wanting to create something that was an extension of my music and could be played more broadly by a broader audience. The Norwood Suite isn't a game that you can lose, it's not a game that you have to suss out puzzles, it's a game that wants to be beaten very gently and it's not an obtuse game in any way. It doesn't present puzzles that aren't particularly brain-twisting, but that was by design and by intent because I wanted as many people to have this experience as possible.

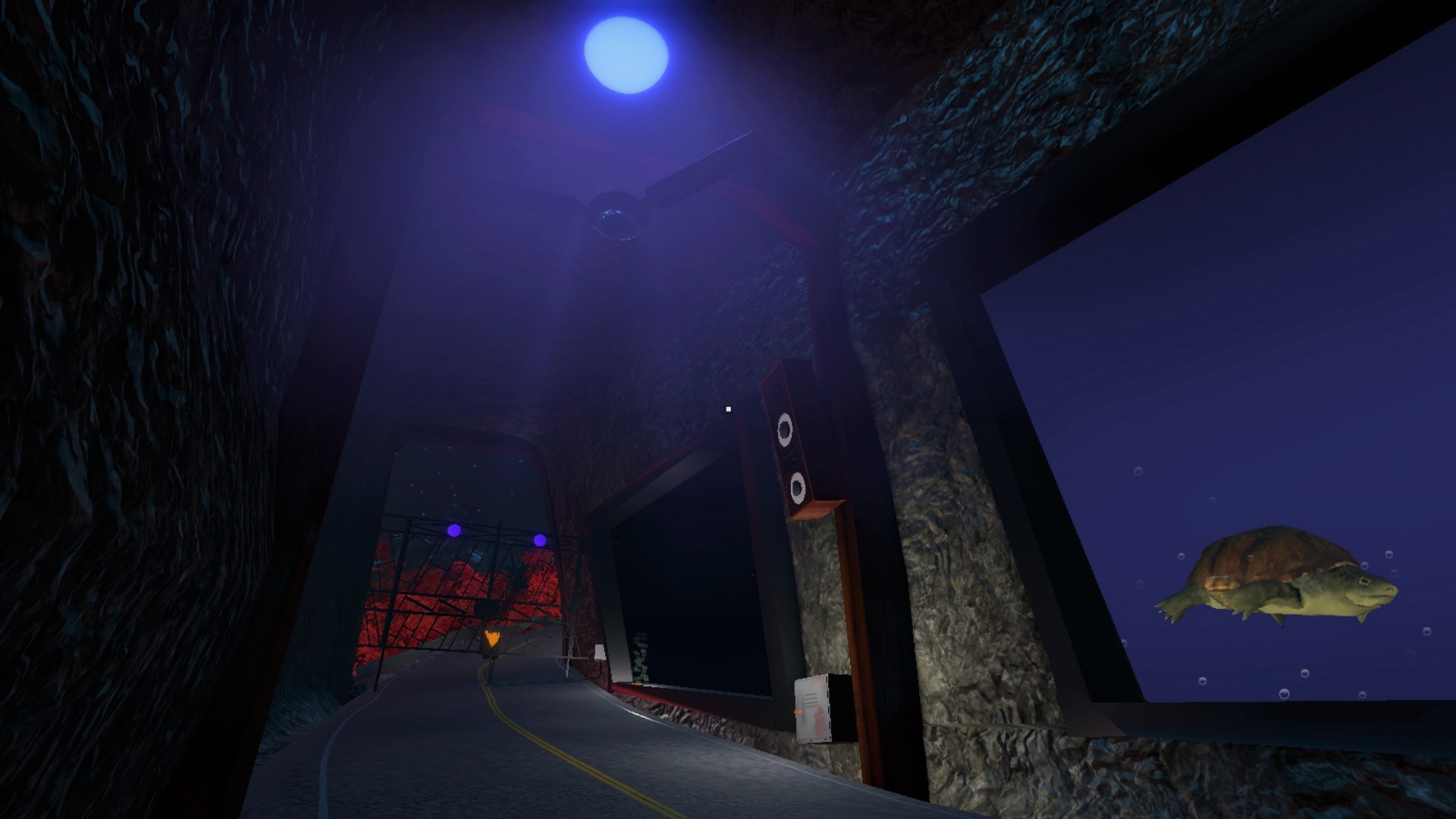

That came more from games like Gone Home or Dear Esther, but the actual vibe, ethos, the nonlinearity and space of it came more from the likes of Thief and those sorts of games where twisting and turning and back passages are key.

What is it about this that you enjoy in particular, are you able to pin anything down in that process?

I love that within those games there is never a right way or a wrong way to play. There were many ways, you learned along the way and in turn had your own experiences along the way. I love that. Coming from other sorts of games that are linear, I've always been drawn to nonlinear spaces. With open world games now, this is becoming a more prevalent thing but when I was younger it was awesome.

When you made the announcement, you said while not wanting to commit to the term episodic, you did say new areas will be added and explored. Is this still something you're interested in doing?

It is, definitely. The Norwood Hotel, the world that I've created, lends itself to a somewhat modular approach in how I expand it. So, rather than going from one piece of a story to another piece of the same story, I sort of intend to complete this arc, but within it there are other stories that can offshoot, like spokes of a wheel. I think the word is anthological—here, everything happens in the hotel, but it's a different experience.

Everything is its own thing, maybe it ties into this, but it's also it's own thing. I like that more because it allows for more self-contained stories within this larger story. I want to at least resolve those stories. Yes, this larger story still leaves a lot open to interpretation at the end, but I also like the idea that you get to complete the arc. So, yes, I do intend to continue to expand on this world, these people, these characters, in a way that feels fresh.

Do you have a rough timeline of when new things might be introduced?

I don't. If I told you, I'd probably have to revise my rough estimate down the road. I would love to continue to add more layers to this story in 2018.

Clearly music gives you an edge when storytelling. Do you think your background gives you an advantage?

Umm… no, I think my background gives me a particular point of view and a particular angle at which I'm arriving at this work. But I feel that my perspective is specific; other people's perspectives might be specific in their own way. There are things that I'm not presenting that other creators might be. It's not like a have an edge, I just feel like I'm coming at it from my own point of view. I'll continue to really lean into that perspective—I know that it's distinctive enough that I'm going to really lead in with and play up.

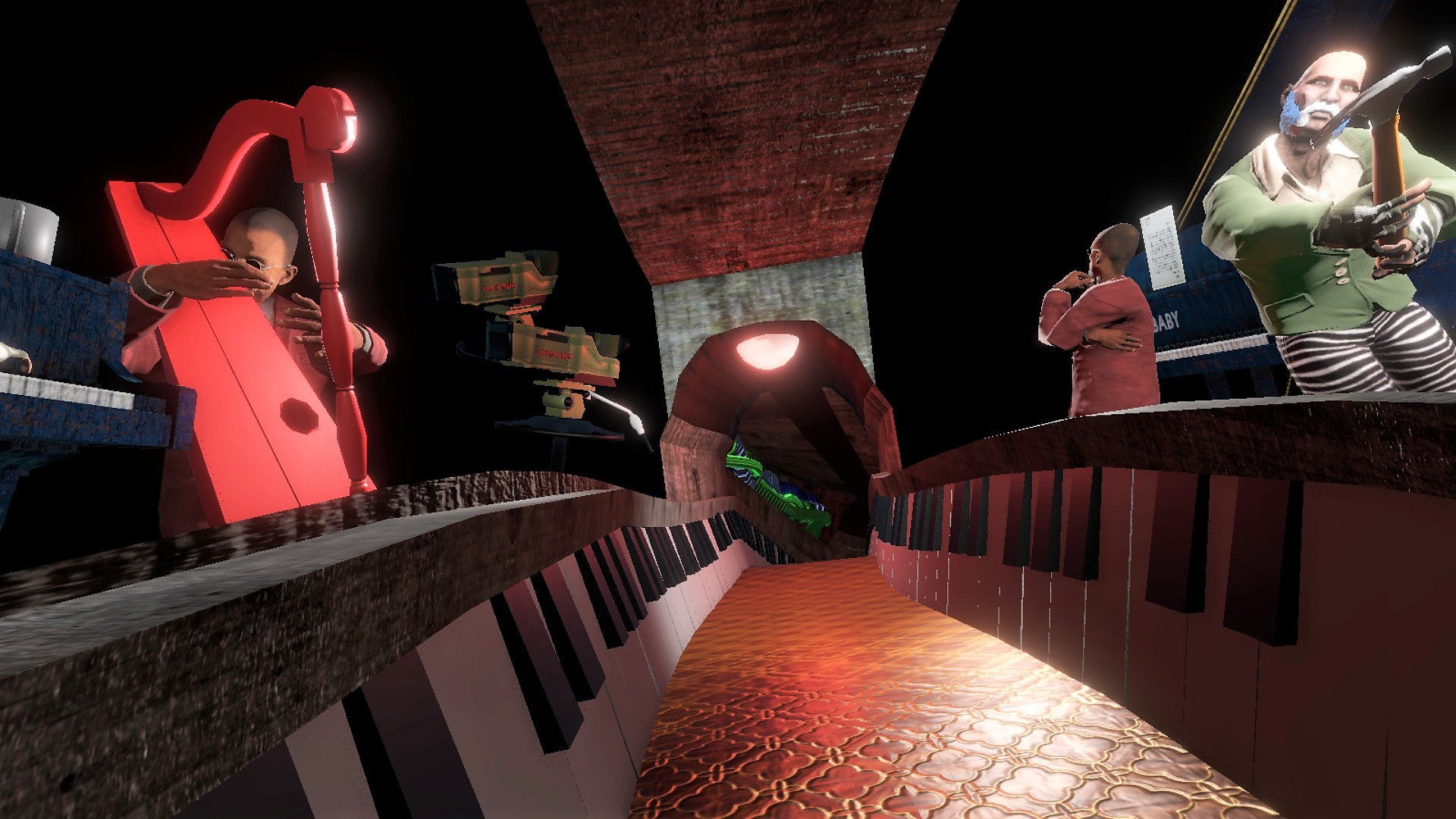

How important is music in telling stories, in getting players to where they need to be—both in-game and in their heads?

That's a good question, because I think that that depends on the game. It depends on how the music is used in the game. Going back to Gone Home: it played both sides, you had the tapes of the rock bands in the world, you could hear the music playing from the tape players, and that was awesome atmospheric touch. You have something similar in BioShock 2 where you play the tape players and hear the music in the world. And then you also have the music that swoops in, that's directed and takes you out of the game. I think there's effectiveness in both approaches. I like music in the world as a matter of immersion, and I think that's just such an interesting experience where you really commit to music in the world, or you play with that.

I also think that there are certain games that benefit from having no music, where the silence, the non-music is its own musical choice. It's like the lack of a score creates this negative space where you have to fill in the blanks in that sense. So, yeah, I think music, however it's used, is pretty awesome and pretty essential. I always try to be sensitive to that. I feel like you have a game that doesn't really think too much about its music, or if you have a game that pays particular attention to its music and how it's executed, then it's going to bring so much more to the game—even if it's the same game.

While they exist in the same overarching universe, it, to me at least, feels like the narrative is a lot more intentional in The Norwood Suite. Is that fair to say?

Yeah, it is. Off Peak was the first long-form thing that I did with the intention of making a complete game. But it was still short it was 20-30 minutes, whereas this to me felt like the next step beyond that. It was less shooting from the hip and going in with more ideas in mind, writing the music more intentionally to the game—everything just felt more, like you said, more intentional. Throughout there were thoughts I was having, trying to connect these dots that were different perspectives on the same topic. And that topic tended to revolve around music and artists and artists finding a place in a hostile, shifting environment. This is something that's true to my life and true to the lives of people that I know. Norwood was about taking this on with a bit more space and a bit more patience.

That said, I think in your games, Norwood in particular, much of the detail is left for the player to interpret—is this a conscious decision?

Absolutely. I don't ever want to explain what the game is in such explicit terms. Whether that's the environmental storytelling I'm doing or whether it's the symbolism around it, I trust players to come to their own terms. I love that. I like giving the players a sense that it's up to them. That it's their call, giving them just enough so that they have some dots, but then letting them connect those dots as they see fit. And maybe then having them talking about it—it's a little bit of theorycrafting, it's a little bit of water cooler talk. I love that, having people asking: What do you think this means, or what do you think that means? It becomes more theirs if they have the space to claim some sort of interpretative ownership of the work and I think that's good. I want them to have that.

What was the biggest challenge moving from Off-Peak to the Norwood Suite?

The biggest challenge was probably making sure it worked. Operating on a bigger canvas but still being a team of basically one until the very end was challenging. There was a lot more moving parts, there were a lot more systems in the game compared to Off-Peak, there was a lot more detail involved. Being able to scale up my skills with that and be able to fix all the issues—technically it was an exponentially larger challenge. And so, yeah, making sure the game didn't break, the technical challenge was the hardest. Also, committing to the scope was challenging and making sure it felt right.

Given the wide variety of indie games available today, how important is it to be doing something different, to make your game stand out?

It's essential, especially now. You really have to come with an original concept and you have to execute it well. You have to come with every box checked in a sense. That's an ongoing challenge. It's important to come with something original, an aesthetic, and making it as accessible as possible. The Norwood Suite has a demo on Steam, the soundtrack is on Bandcamp so it's as accessible as it can be. It's about giving players hooks to get themselves involved, I think that's massively important right now. These are things that coincide with the fact the game has to have a look and have an angle.

What's next in the immediate future?

Continuing to support the game, addressing any technical issues, thinking about ways to keep the game going. Beyond that, it's an open road for me. I want to continue seeing what the response to the game is like and what the next move is beyond that. I wish I could tell you but it's too soon to say right now. I don't really have an agenda, so to speak, I'm taking things in before I start putting things out again.