Our Verdict

In ten hours of criminality, 2K Czech have made the perfect elegy to the mafia movie. Could have been more of a game, though.

PC Gamer's got your back

The chronic oversaturation of the mafia in our international media has taught us much. Mafia II is an attempt to chronicle these teachings in game form. Fact number one: mafia men do lots of killing. Fact number two: they like suits. Fact number three: mafiosa don't call each other mafiosa; they use the term 'wiseguys'.

I've cross-referenced facts one and two with Mafia II, and they're definitely right – a lot of killing and a lot of suits. Fact number three isn't. 'Wiseguys', with its implied streetsmarts and cunning, doesn't fit Mafia II's mobsters. It certainly doesn't fit the mid-level gangster the game asked me to tail early in its middle act, who didn't have the presence of mind to check his rearview mirror as he drove away from a literal hatchet job. Had that guy done so, he'd have seen Sicilian-born WWII veteran and new-boy mobster Vito Scaletta about 20 feet behind, dressed in a red and white cod- Hawaiian shirt, driving a hot pink corvette with 'BUMS12' proudly displayed on the numberplate. That guy was not very wise.

Wise up

The other guy was me, and I was trying to be too wise. As Mafia II's protagonist, my first attempt to trail the escaping mobster ended in failure after my original car choice – an inconspicuous '50s saloon – was outpaced with ease on the motorways. I only chose that car, snatched unattended with a bit of pavement minigame lockpicking, to satisfy the mission briefing, which said my mark would notice anything too obvious. Dutifully I wrested against the vehicle's slightly clunky era-specific handling to try and keep pace. But after my AI target had pranged his own vehicle six times against anything and everything in his path, I realised that such forwardthinking wiseguyishness wasn't entirely necessary on my part.

That Mafia II so effectively harpoons its illusion of real life, showing its characters to be machines acting out prescribed paths, is to its detriment. But the fact that I bought into it in the first place is the game's greatest strength.

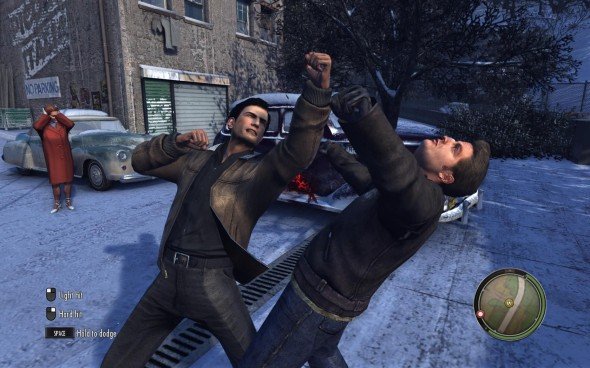

It's not that Vito is a sympathetic character. Returning from a war he held no moral stake in – after a botched robbery, it was that or prison – he joins the local mafia, even though his mum told him not to. Naughty. From there on, he relies upon menace through the typical mafioso triple-threat: punching, shooting, and scary staring. Best buddy Joe occasionally dips a toe into 'comic relief' territory, but then ducks back into 'just a bit nasty' land, gets his pistol and shoots everyone in comic relief territory. Those poor clowns.

The player's supporting cast eschews any chance to get really creative, instead furnishing the game with another layer of dark-suited, dark-haired professionals, hitmen and higher-ups that blur into one mass. Driven by his need for money and respect, Vito is encased in a series of ever-widening shells, each step up the mafia ladder (a ladder made of guns) giving a new set of faces to watch in cutscenes: but they're all congealed clichés, culled from a hundred Bronx Tales and Godfathers. The dialogue is wellwritten and excellently acted, but it feels mechanical, the spoutings of a supercomputer sat in a shady office with its dials set to 'lightly-accented macho threat.'

City of dreams

It was the city that drew me in. An amalgamation of New York's streets and Hollywood's hills, Empire Bay is as interactively sterile as all other 'open-world' game-cities, but it's been coated in a veneer of dreamy credibility. Each street and hallway has a feature – a man shouting at an open window; a woman pressing her ear to a door; the sound of an argument. It's easy to see these details written down in a design document, but it gives Empire Bay a genuine rhythm, a pulse that Liberty City lacks. Plus, it helps that it is – on hefty machines – stunning. Turn up in the city in winter, and the streets are caked in snow, with layered bands of crystalline white on the untrodden paths contrasting with slush on the roads. And the lights! Even as the game transitions out of the 1940s and into the '50s, Mafia II's waxy lighting remains consistently arresting, casting pools of gold and yellow on windscreens.

But there's no point to any of it. The city breathes and grows, changing as the missions span the years, but it never moves or cries out. The game is presented in chapters, and each chapter has you wake up in your home. Vito, I can inform you, is a man who sleeps in the same vest and pants for nine years. Before the poor, smelly bugger can even get dressed, he's hit with news and a job. The game forces you to drive to a location: once there, Vito either shoots some men, punches some men or drives to another location.

As their cheery local mafia man, I'd pop in to see my contacts. Need any guys whacking today? Anything nicked? Want me to punch a lady? I was good at all these things. But, always, no. To deviate from the missions just wastes time: you can rob shops, but won't procure much loot; you can pester civilians, but will only get police pressure. For a city dripping with incidental detail, the game slapped on top of it has none. Not that this is a mechanical problem – 2K Czech have never made any bones about Mafia II being a linear experience – but when the city itself looks so inviting, it's a shame you can't do more.

Incidental chaos

Unless you make your own fun, that is. I enjoyed people-watching in a city where every pedestrian and car driver has the situational awareness of a frightened rabbit. Drive near one of the AI humans on foot and their preset reactions kick in, launching them in a seemingly random direction. Sometimes, this would be toward safety; more regularly, they'd hurl themselves into speeding traffic.

Having a woman – a few moments earlier happily strolling down a sunny street – chuck herself in front of a nearby van is certainly a surprise. Having that van then swerve to try to avoid her and plough through another three pedestrians is brilliant. Having that van then be spotted by a police car, having those police open fire before getting squished by the panicky, blood-leaking van driver, is better than another cover-shooting 'kill 50 goons' story mission.

And those are too regular. Combat is supported by a pleasing system of gunplay that leads to weighty, inaccurate firefights heavily reliant on ducking behind cover. The enemy AI – so stupid at the wheel - doesn't redeem itself through Mafia II's battles. Bad guys just pop up and down from the same spots of cover like sharply dressed moles: whacking them is simply a matter of waiting. Early in the storyline, Mafia II displays a convincing unwillingness to murder indiscriminately, surmising that the repeated and wholesale murder of swathes of humanity isn't the mafia's major focus. This was the time I built my connections, prepared my lip for wobbling when my contacts became friends and my friends went to sleep with the fishes, as all mafia friends do. But then, three quarters of the way through, it forgets all that, and puts you up against waves of baddies, dehumanised after all that work to build Empire Bay's factions into tangible things.

Mafia II is a mafia movie run once through a game grinder, and that's simultaneously the worst thing about the game and the compliment it was developed for. In telling a story as convincing as most Hollywood depictions of the Cosa Nostra, 2K Czech have accomplished exactly what they intended to: only at the end does the artifice topple slightly, piling one too many game-cliché mass-battles onto the pile. But detach the story from its very familiar housings, and we're not left with much: a bit of walking, a lot of driving and too much shooting. Each is good, but rarely superb.

Even supported by a neat script and great voicework, Mafia II is treading ground already chewed up by cinema's very best. On that level, it can't compete. On the level it can – that of the gorgeous Empire Bay – it shows an unwillingness to try. It's a compelling experience, but an offer you can refuse.

In ten hours of criminality, 2K Czech have made the perfect elegy to the mafia movie. Could have been more of a game, though.